Note: The California Bicycle Coalition is preparing to release a report, Incomplete Streets: Caltrans Fails to Protect Vulnerable Road Users, in August. This post is the second in a series of excerpts from their research.

Caltrans’ Complete Streets policy, DP-37, states in bold type: “all transportation projects funded or overseen by Caltrans will provide comfortable, convenient, and connected complete streets facilities for people walking, biking, and taking transit or passenger rail unless an exception is documented and approved.” The question is, what constitutes an exception? The answer appears to be: almost anything.

On some of the projects in the State Highway Operations and Protection Program (SHOPP) reviewed by the CalBike team, the reasons for not including desirable active transportation infrastructure seem logical. For example, extending the shoulders on a rural route to accommodate people biking and walking might be infeasible in a mountainous area where extensive engineering would be required to widen the route.

However, more often the reasons given for excluding Complete Streets elements seem to boil down to some version of “we don’t want to.”

A 2024 SHOPP project on 8.5 miles of Beach Boulevard in Orange County uses an all-too-common rationale for ignoring the directive in DP-37 to make state routes comfortable and convenient for people biking, walking, or taking transit: The purpose of the project is car lane rehabilitation, and the $5 million in [lackluster] bike and pedestrian improvements excluded from a $46 million repaving project “can be explored or incorporated on future projects on SR-39” (see p. 154). That is: perhaps some mythical future engineers will view their jobs as serving all Californians, unlike today's road builders.

Ocean Access — If You Have a Car

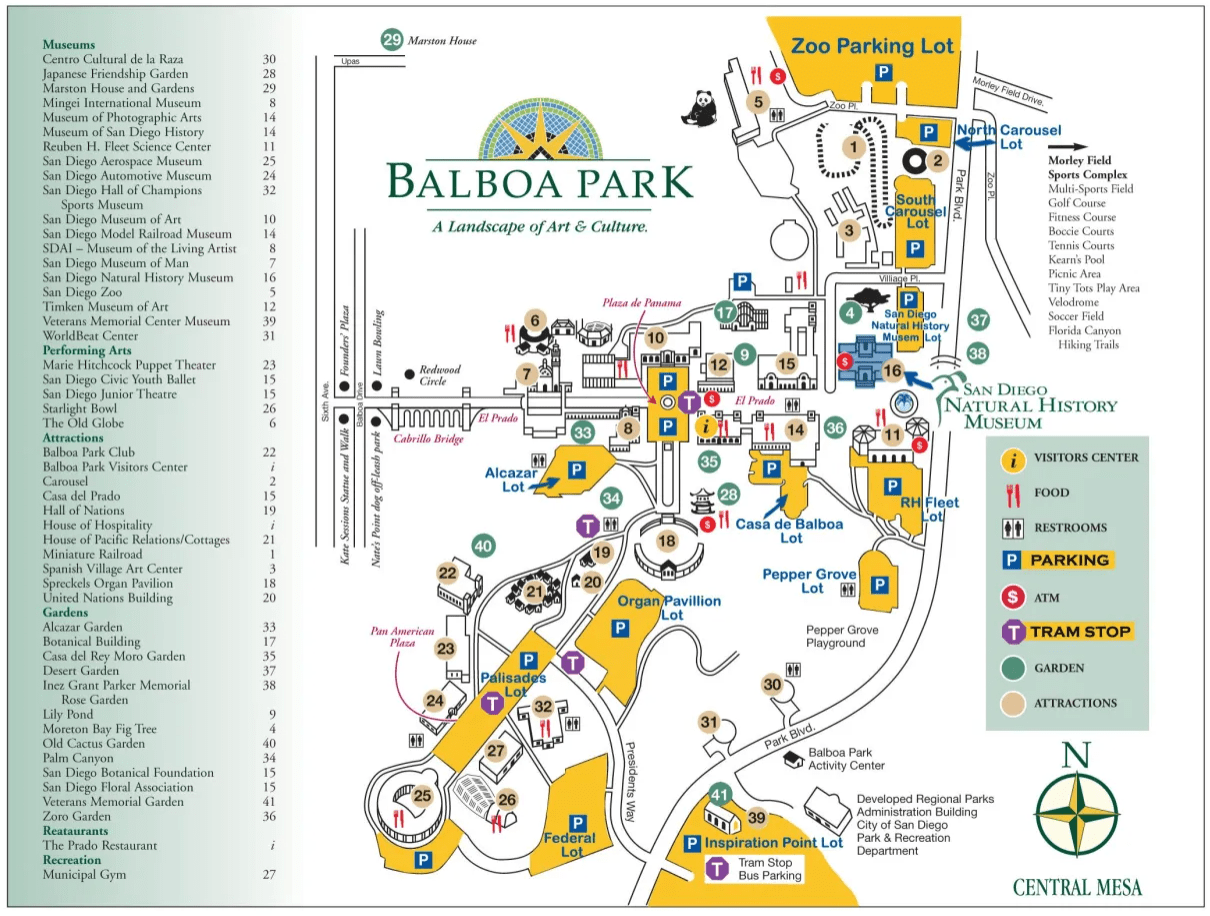

Beach Boulevard (State Route 39, or SR 39) is the longest continuous north-south arterial in Orange County. The corridor extends through nine cities (Huntington Beach, Westminster, Garden Grove, Stanton, Anaheim, Buena Park, Fullerton, La Mirada, and La Habra) as well as through unincorporated Orange County, and is primarily under the jurisdiction of the California

Department of Transportation (Caltrans).

Like many of Caltrans' “main street” highways that also serve as a local surface street for those cities, Beach Boulevard is a fully developed residential and commercial corridor and is heavily used not just by people in cars, but also by many people walking, biking, and using transit to access destinations along its length. Beach Boulevard does not prohibit access to people outside cars, but it dedicates the vast majority of its available space to six to eight travel lanes for cars, and narrow or no infrastructure for people walking other than incomplete sidewalks and widely spaced crosswalks.

There are no marked bike lanes along the entire length of Beach Boulevard/SR-39, though people ride bikes there, and likely many more would choose to ride if a comfortable bike facility were present in the corridor. There are many sidewalk gaps, and the street lacks frequent and safe street crossings.

The share of transit trips on Beach Boulevard is significantly higher - almost double - that of Orange County as a whole; for work trips only, transit on Beach Boulevard serves 2.5 times as many people as the county average. Yet, despite two major bus lines on the corridor itself and interconnections with 25 bus routes, there is no transit-priority infrastructure that would speed up buses so they aren’t waiting in traffic, and the 2024 SHOPP project we reviewed didn’t recommend any infrastructure improvements to support transit riders.

Dangerous by Design

Beach Boulevard is one of the most deadly Caltrans “main streets” for people walking and biking. Over the last decade, there have been 78 vulnerable road users killed on the street, and pedestrians and people biking account for nearly 70 percent of all road user deaths on SR-39. This is a significantly disproportionate share, since most people traveling on Beach Boulevard are in cars. It’s also much higher than the 27 percent statewide share of all traffic fatalities that are pedestrians and bicyclists. The wide street has speed limits of 40 to 50 mph and is particularly dangerous for people outside of cars due to these high speeds and the lack of protective infrastructure.

In addition, more than 700 people walking or biking have been seriously injured in the last ten years on Beach Boulevard, and that counts only official police reports; many collisions go unreported, so that number is undoubtedly higher.

Unlike local governments, which may respond to community pressure and fix dangerous infrastructure, especially after someone dies, Caltrans’ response is tepid or in some cases entirely non-responsive to the carnage its streets inflict on the people who use them.

The Beach Boulevard project documents we reviewed included detailed injury and fatality statistics broken down by small segments but not by travel mode (pp. 1-4). The project documents don’t indicate that, without the recommended infrastructure improvements, Beach Boulevard will continue to have these high death and injury rates among bike riders, walkers, and transit riders.

Ignoring Documented Needs for Active Transportation Infrastructure

In the past six years, Caltrans (District 12), the Orange County Transportation Authority (OCTA), Kittelson & Associates, Inc., and several other private planning firms have officially documented the high need for safe street infrastructure on Beach Boulevard, saying that it should be a priority for road repair projects.

A study to improve Beach Boulevard was conducted and concluded in April 2020, while a Caltrans Active Transportation (CAT) Plan for all of District 12 was finalized two years later. Many bike/pedestrian needs were identified in the planning phases by Caltrans/OCTA, including transit signal priority treatments, pedestrian scrambles, and protected bikeways.

The Beach Boulevard Corridor Study and District 12 CAT Plan assessed existing conditions, forecast future growth, and proposed solutions ranging from enhanced pedestrian, bicycle, and transit facilities to improved signal synchronization. These plans also prioritized the need for Complete Streets facilities to implement the multimodal transportation vision and stem rising vulnerable road user fatalities.

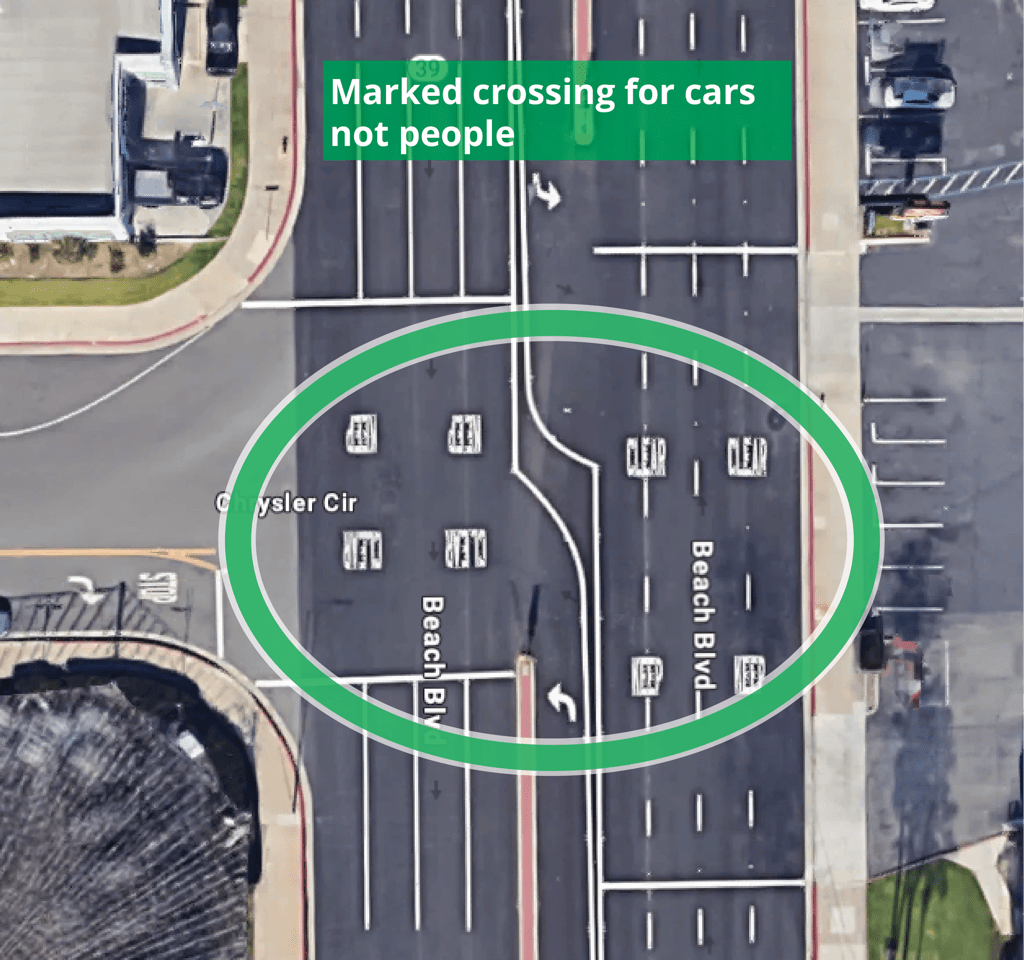

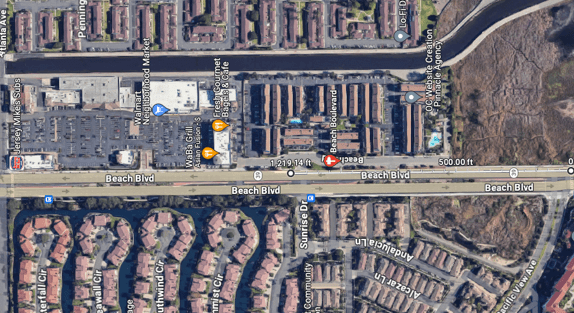

In the very first block of Beach Boulevard, where it starts at the Pacific Coast Highway adjacent to beach and trail access, pedestrian needs are glaringly apparent. The distance from the first pedestrian crossing, at the PCH intersection, to the next, at the intersection of Pacific View Avenue, is 755 feet. The NACTO Urban Design Guide states that “there is no absolute rule for crosswalk spacing,” but recommends 120 feet to 200 feet between crosswalks. Since there is no cross street in the first 755 feet of Beach Boulevard, Caltrans would have had to create midblock crossings.

However, the distance to the next crosswalk, at Atlanta Drive, is 2,419 feet — nearly half a mile — despite multiple cross streets. Two bus boarding islands are located in the middle of the block, more than 1,000 feet from the nearest crosswalk, or about the length of three football fields. If a transit rider needed to get to the bus stop across the street, they might have to walk as far as six football fields, a time-consuming trek that may be impossible for seniors, people with disabilities, or most travelers on the increasingly frequent days with extreme heat.

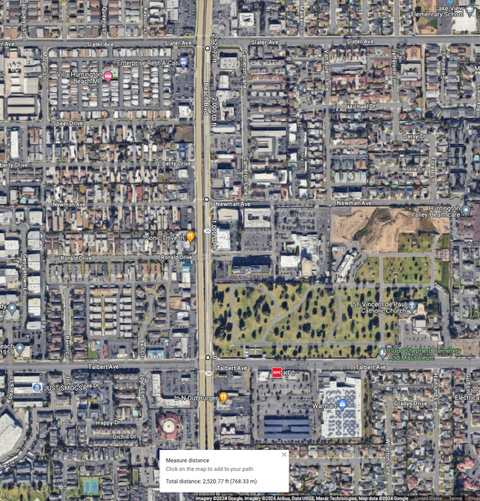

This block is not an anomaly. As Beach Boulevard traverses urban neighborhoods of homes and businesses, most of the blocks are around half a mile long, with few midblock crossings. The shortest distance between crosswalks is 500 feet, more than twice NACTO’s recommended maximum.

The corridor goes under two freeway overpasses, crossing the on- and off-ramps, which sometimes have poorly marked or missing crosswalks. While the SHOPP project does include 98,150 square feet of crosswalks, these are likely locations where Caltrans will simply restripe existing pedestrian crossings without adding new ones. And the SHOPP project doesn’t include a modest $1.5 million recommendation for closing sidewalk gaps along the dangerous, high-speed corridor.

What happens when Caltrans refuses to include adequate infrastructure for people biking, walking, and taking transit, and continually pushes those needs to imaginary future projects? More than 700 people have their lives upended by injuries, 78 families grieve the loss of someone who will never come home again, and the death toll on this road continues to rise for the next decade. It is shameful.

Implementation (or Lack Thereof)

Over the past several SHOPP cycles, there have been four Caltrans projects programmed on Beach Boulevard. The largest pavement rehabilitation project is this project, from Huntington Beach to Westminster, in the 2024 SHOPP. The project boundaries are identified as including the highest-collision areas along the entirety of Beach Boulevard for people walking and biking, yet Caltrans chose to implement only minimal, required ADA improvements (similar to District 3’s approach described in our last Incomplete Streets post). It declined to close sidewalk gaps or add bikeways, even though those were recommended improvements and would have added barely more than ten percent to the project cost. Once again, Caltrans continues to ignore documented needs for vulnerable road users and misses a major opportunity to live up to its own directives.

The casual dismissal of well-documented bike and pedestrian needs in the Complete Streets Decision Document for this project emphasizes Caltrans districts’ carelessness about the lives and safety of people biking and walking, and for the agency’s own policies. Caltrans hides this disregard under complex and lengthy technical documents viewed mostly by agency staffers. CalBike is requesting and making these documents - which belong to the citizens of California - available to the public so our elected leaders can understand the urgent need for better oversight of this renegade agency and the false hope that Caltrans was taking a new direction, as expressed by Governor Gavin Newsom when he vetoed S.B. 127 (Wiener) in 2019.

Jared Sanchez wrote this report with assistance from Kendra Ramsey and Laura McCamy from CalBike and Jeanie Ward-Waller from Fearless Advocacy.