Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

A profound change is coming to the way California plans and develops its cities. For years, congestion has been the only way the environmental impact of car travel has been accounted for under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Level of Service (LOS)--a measure of how long it takes cars to get through a segment or an intersection--wormed its way into CEQA by habit and practice until it became the de facto measure for how cars affect the environment.

The result has been countless planning decisions leading to unwalkable, unbikeable cities with wide, fast, many-laned streets. The use of LOS has discouraged efficient infill development, by making it difficult and expensive to develop where traffic is already busy, while encouraging sprawl and edge development. That has made our cities highly--and dangerously so to our health--dependent on cars.

And it's all in the name of keeping cars moving. People on foot and on bikes are not only left out of the LOS equation entirely, they are endangered by resulting road designs that are difficult to navigate and cross safely if you're not in a car.

A Profound Shift, Long in the Making

Starting July 1, CEQA will instead require developers to measure how many miles of vehicle travel a project will produce. The effect on cities may not be immediate, but it will be profound in the long run. It has the potential to change the way planners consider projects, to end long-standing practices that encourage car dependence, and to prioritize infill, mixed-use, and transit-oriented development rather than sprawl and edge development.

Regular Streetsblog readers know that this change has been a long time in the making. A 2013 law, S.B. 743, required the state to find a new way to measure the environmental impacts of traffic, and it has taken this long to dot the i's and cross the t's. The Office of Planning and Research, which led the work to design and implement the changes called for by S.B. 743, has been offering webinars outlining what planners need to know going forward, and has plans to hold online "office hours" to further answer questions. With the deadline for adoption looming, interest in the topic is high; the webinars have been filling to capacity and OPR has added additional ones. (There's one happening Monday, April 20, which can be streamed live on YouTube here--or watch the ones that have already streamed.)

In a separate move, Caltrans also just released draft guidance on its plans to apply S.B. 743 to transportation projects. The department plans to use the vehicle miles traveled (VMT) measure on state highway projects that increase capacity.

This could be a game-changer for state highway planning and funding.

Several important things to note:

---Caltrans has developed its own timeline for transportation projects to start using VMT instead of LOS, based on where they are in the planning process. By September, most projects not in advanced planning stages will have to start using the new measure. More information can be found in the Caltrans timeline, available here.

---Questions have been raised about whether the deadline might be extended due to the pandemic. This seems unlikely, for two reasons. First, as a statutory deadline it would require legislative action to change--and the legislature is currently not in session, and unlikely to tackle more than the most urgent measures when it does return. Second, a recent court case, Citizens for Positive Growth v. City of Sacramento, ruled that LOS is not a valid measure of environmental impacts under CEQA. The only other potentially valid, and vetted, measure is VMT, so any delay would be meaningless at best.

---Some areas have already adopted VMT as their measure of the environmental impact of transportation, including Pasadena, San Jose, Oakland, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Luis Obispo. Other areas may continue to rely on the Level of Service measure for other planning processes, such as in their General Plans, but LOS has already been deemed inadequate under CEQA, as noted above.

---Many projects are newly exempt from measuring any traffic impacts under CEQA--for example, highway projects that don't increase VMT. In addition, OPR presumes that certain types of projects will either reduce VMT or any additional VMT they produce would be "less than significant" and as such they are exempt from having to produce a transportation analysis at all. These include bike and pedestrian improvements, infill projects, locally-serving retail, and transit-oriented development--although OPR's Chris Ganson, at Thursday's webinar, warned that projects that replace existing affordable housing with market-rate housing, even if they are "transit-oriented," would have to account for VMT changes from displacing residents.

CEQA Streamlining for Projects that Won't Produce More Driving

Ganson pointed out that this streamlining has many benefits, including encouraging more compact, efficient development. It can also help preserve the character of small towns. "Small towns perform very well on a VMT metric," he said, "and using VMT to measure traffic impacts can help preserve the small town feel, even as they develop," whereas the old LOS metric could force them to widen streets and push development outward. In many cases, that has contributed to the emptying out of downtowns, whereas the new VMT measure will allow those downtowns to develop.

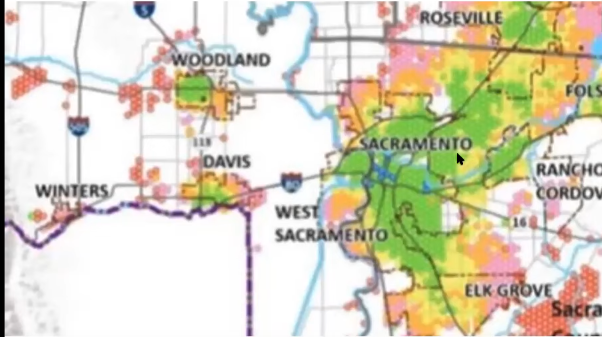

OPR has produced maps that show which areas in the state can skip the transportation analysis. People assume that centrally located downtown housing will be streamlined, said Ganson, and that is true--"but it also applies in many inner suburbs and small cities." He showed a map of the Sacramento region, where many areas, including, for example, large swathes of Roseville, are in the streamlined zone.

And even outside of those zones, cities will benefit when projects measure traffic impacts using VMT, which will favor developments that don't encourage more driving. Also, eliminating the need to do an LOS analysis will make the CEQA process easier altogether, since VMT is simpler to calculate. Planners are already suing VMT in other areas of planning outside of CEQA.

Not Just About the Environment

The policy shift is not simply a response to environmental concerns. "It's not just doing something for the environment at the expense of the economy," said Ganson. The old LOS measure, which prioritized traffic movement above all other considerations, brought serious side effects. It encouraged development outside of city cores, putting housing, jobs, and shopping farther from each other and harder to get to without a car. By prioritizing car speeds, it encouraged more driving, which ended up creating more congestion and adding to pressures to develop farther and farther away from city centers.

All of that constricts economic activity; it increases the amount of expensive pavement needed as well as maintenance money needed for that pavement; it makes transit less efficient and a lot harder to plan. It also contributes to sedentary lifestyles that include hours sitting in cars that could have been better spent in less stressful, more active ways, instead leading to increased chronic disease as well as overall health care costs.

Kate Gordon, the OPR's director, introduced Thursday's webinar by talking about why the new focus is needed. The buildout of the national and state highway systems in the last many decades allowed cities and suburbs to develop, but its long-term effect has been to encourage more driving and driving much longer distances.

Even so, she said inland areas of the state didn't see the same economic boost that coastal cities have, and now even very rural areas are feeling pressure to develop more housing as people seek affordable areas to live--but without jobs nearby. This has caused ever longer commutes, which among other effects has made it "hard to participate in community life. It seems strange to talk about this right now, when people are staying home and spending a lot more time with their families--but this is the reality of the development patterns we have encouraged," she said.

Privileging driving led to worsening congestion in both rural and urban areas, contributed to rising housing costs as people who could afford to do so moved closer to jobs and people who couldn't were forced to spend more money on transportation. This also contributed to "rising homelessness in cities in part because people cannot afford to live anywhere near their jobs."

The U.S. also has twice as many traffic fatalities compared to most countries, partly because so many people spend so much time in cars. Then there are the bad health outcomes, including premature deaths, from sedentary lifestyles.

The conversion of agricultural land to housing at the margins of cities, said Gordon, makes some sense at first glance in terms of saving money. Geenfields are cheaper to develop, and the CEQA process has contributed to that because new edge developments are less likely to show an increase in congestion because they are farther away from other land uses. These converted ag lands, however, not only were potential local sources of food, frequently served an important function as fire or flood buffers for towns and cities, and building on them increases the danger of both.

Then there is the issue of rising carbon and other emissions, which need to be significantly cut.

"Lessons we have learned," said Gordon, "include that we cannot widen our way out of congestion, and in many cases all we do is simply add vehicles. We want to give Californians the choice not to be stuck in traffic. That will take investment in transit, but also new development patterns that bring jobs near housing as well as housing near jobs, to give people the option of more walkable, bikeable, short-drive lifestyles."

But, she reminded listeners, "S.B. 743 is only one tool in the toolbox." It applies only to the CEQA process.

Nevertheless, this shift in policy will be profound. Combined with other efforts to increase housing and decrease driving, they could fundamentally change the feel of cities and towns in the future.

How It Will Work: Lead Agencies, Local Policies Will Decide

The Office of Planning and Research has been offering webinars, meetings, and guidance documents for several years now on how to make the shift, and these webinars go into a lot of detail.

One ongoing area of their work is on what kind of mitigations would be appropriate for projects that increase the number of miles traveled.

Under CEQA, when a project is found to have a "significant impact" on some aspect of its required environmental checklist--such as noise, land use, air quality, cultural and biological resources--it must do something to mitigate the problem. If a project can't do that, planners can issue, and must defend, a "statement of overriding considerations."

Under LOS, mitigations included widening roads and putting in new signals and adding lanes so as not to slow down traffic. Reducing vehicle miles traveled will take very different kinds of mitigations. Ethan Elkind, director of the climate program for the Center for Law, Energy, and Environment at UC Berkeley, outlined some of those potential mitigations. They could include pricing incentives, such as charging for parking; changing the design of a project in some way, such as putting housing and jobs together on the same site; or paying for transit or active transportation projects, such as by offering residents transit passes or improving local pedestrian conditions.

Elkind and his colleague Ted Lamm also led a discussion of mitigation banks, which could allow developers an "escape hatch" to provide some kind of mitigations off-site. One argument for creating such a system, they said, was that it could avoid having an agency just issue a statement of overriding consideration because they can't figure out how to mitigate. But many issues remain to be worked out, including equity (who would benefit?), scale (how wide an area would be covered?), and not allowing credit for mitigations that would happen anyway.

Ramses Madou, who helped lead the development of San Jose's VMT policy, talked about that city's experience with the changeover. He offered access to the city's VMT calculator, which could be adapted by other cities to suit local needs. That calculator, he said, has helped significantly streamline San Jose's process, and also gives developers an immediate idea of what VMT changes might be associated with their project so they can start thinking about mitigations from the start.

Still, the process is new. "There's a lack of research on how particular changes to the right-of-way help mitigate VMT," said Madou. "This will develop as cities get more experience with it, but right now there's no clear statement about what works and what doesn't."

OPR is leaving many details up to the lead agency on a project, and to locally determined policies; these include VMT thresholds, appropriate VMT mitigations, and the definition of "locally serving retail," for example. But all must be backed up by "substantial evidence," which OPR provides on its website here.

The main point of all this is that, at long last, a huge barrier to efficient people-friendly development is being removed from one significant part of the state planning processes. The goal, as stated by OPR's Gordon, is "to make our state more sustainable, more inclusive, and more resilient."