The biannual California Bicycle Summit just wrapped up in Sacramento. Several hundred people gathered to talk changing the world through better bike access for all, and many related topics. The summit featured inspiring talks, spirited debate, and detailed policy discussions. An overall theme was transportation equity and justice, which generated several wide-ranging discussions about how to bring more people to advocacy work.

Without claiming to be at all comprehensive, below are a few highlights:

Equity, Advocacy, and Transportation Justice

One afternoon featured the “lunchtime entertainment” of René Rivera, Bike East Bay Executive Director, and Jeffrey Tumlin, a principal with NelsonNygaard and until recently interim head of Oakland's new Department of Transportation. Although they are indeed entertaining, the two spoke of the serious issues they face as advocates for better transportation that suits the needs of everyone in Oakland.

Rivera talked about the ways Bike East Bay has been working to be inclusive and to build leadership in the community. For example, advocates have been working with other community groups like Rich City Rides and the Scraper Bike Team on issues as diverse as local sales tax measures and making bike-share available to low income people. Bike East Bay also works to highlight and discuss issues like racial bias in traffic stops in the cities where it advocates for better bike policies and planning. It also brought a League of American Bicyclists training to Oakland to help create a diverse group of instructors, including women of color, to teach bike education classes in the East Bay.

Tumlin highlighted some of the work his transition team completed during the strategic planning to create Oakland's new Department of Transportation. The first order of business was to “clearly explore our values as a city, and to look at where those values are in tension with each other.” It's important to create a vision, of course, but also necessary is putting your money where you mouth is. “If your values are not aligned with your budget, your values don't matter,” he said.

He started with old maps that showed how Oakland was redlined—in which certain areas of the city were marked off in red, and banks would not offer mortgages nor support investments in the housing stock in those areas. Then he showed other, more current maps that his team put together: maps of low-income areas, historically underserved areas, and maps showing the marked difference in investment levels among neighborhoods in the city. They matched the old redlining maps, showing what Tumlin called “active investment in inequity.”

His point was that historical disinvestment is not a thing of the past. Many people explain the differences between “equity” and equality, frequently using a graphic of people trying to see over a fence—showing how people who start at different levels aren't “equalized” when we spread investments out equally in our communities. We frequently think this is what we're doing, but Tumlin's maps showed that in Oakland, investments tend to go towards the places where investments have already been made.

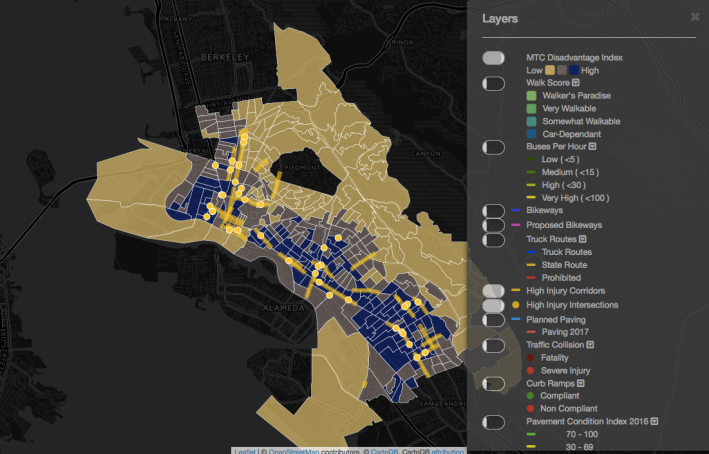

The team invented its own equity analysis tools, creating a “disadvantage index,” and began to score requests for work against that analysis. The data is mapped and available for the public to see, to manipulate, and to understand where problems are being addressed—and why the city needs to push resources towards the areas where the needs are greatest. The maps include information about the disadvantage index, walkscore, bus service frequency, bikeways, truck routes, high injury areas, and pavement condition and paving schedules.

California Walk & Bike Youth Leaders Program

CalBike, California Walks, and the California Center for Civic Participation inaugurated the first Walk and Bike Youth Leaders program, in which young people aged 16 to 23 gathered to discuss their experience of transportation access in their communities throughout California. In the process, they created videos to show the challenges faced by their peers in moving about their neighborhoods.

Those videos—not available online yet—inspired a spirited conversation about what people can do to bring attention to problems in their communities, and how youth can lead community efforts to fix them.

Connecting Human Infrastructure

“The bicycle is a tool that allows us to see the underlying ecology of connection between us,” said Dr. Adonia Lugo during her talk. She spoke about the changing bike advocacy movement, that is rooted in making life better for people who use bikes, but can also become a tool for creating other healing projects.

“Right now,” especially given the national political context, “People need a sense of power, of knowing there is an action we can take,” she said. “Bicycling is something powerful that we can do, that can make a difference.” At the same time, a bike can be an intersectional tool that allows people to connect across class, gender, race, and other divisions.

Pragmatic Advice: How to Do a Pop-Up Project

Protected bike lanes are “the hot new thing,” according to one panelist on this presentation, and indeed during the bike summit, Sacramento hosted a demonstration parking protected bikeway, the first of its kind in the city. This panel discussed their experience with all kinds of projects, including protected bike lanes but also pedestrian scrambles (all-way crossing for pedestrians at an intersection), roundabouts (using straw and plants to delineate a space in the intersection), painted crosswalks, bulb-outs, and parklets.

Alek Bartrousouf of Southern California's Go Human campaign said that they have eighteen such projects planned for the next year. Pop-ups and demonstrations allow planners to demonstrate new infrastructure on the ground where people can immediately understand in a way they can't when they're just looking at a drawing or a map. Pop-ups “should replace studies and endless community engagement to find the perfect project,” said Bartrousouf. They can be put in quickly and inexpensively, and they can be removed if people don't like them. They are also an excellent way to get feedback from people who encounter them, and to refine them before any permanent changes are made.

Dave Campbell of Bike East Bay talked about several pilot projects in Berkeley and Oakland that have been lessons in coordinating transit agencies, city agencies, local business groups, and advocates. One project started as a pilot to create bus-only lanes along Bancroft, a busy street lining the south side of the UC Berkeley campus. AC Transit wanted to include bikeways as part of the demonstration, to help figure out ways to solve conflicts on the street between bikes, cars, and buses.

That allowed the city to plan a more complex demonstration project that will include a bus-only lane along the right side of the street, with a two-way parking protected cycle track on the left side which will allow bikes better access to the UC campus. That project, which was supposed to be in place before school started in August, should be on the ground any day now.

The Gas Tax and Making Transportation Better

Another panel discussed the recently passed California gas tax, S.B. 1, and the various programs that will be funded by it. Jared Sanchez, Policy Associate for CalBike, discussed the ten principles for transportation justice that CalBike and its partners had submitted to the California Transportation Commission (but which haven't gotten a lot of attention from the commissioners).

There are a lot programs that will be funded by S.B. 1, among them the Active Transportation Program, which will receive a relatively small amount that will nevertheless double the program to $100 million annually. Other programs are still being formulated, among them one called Solutions for Congested Corridors, which will get $250 million per year. That pot of money is specifically prohibited from being used for general purpose lane expansion, in recognition that the state can't build its way out of congestion. But what it will be used for is still being discussed. Even the definition of congestion in the program has yet to be nailed down. CalBike and allies recommend focusing on reducing miles driven rather than getting more cars through an area, but nothing has been decided yet.

There was more—much more—to talk about at the summit. There was an entire thread on bike-share, detailed discussions of specific examples of bikeway design, a panel on rethinking the rules for setting speed limits—the list is long and deep.