Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

The Senate Transportation and Judiciary committees held a joint hearing yesterday on the conflicts between cities' need for data on what is happening on their streets vs. protecting consumer privacy.

The questions it raised about who collects what data, who has access to it, and how they use it, for the moment, is focused on "mobility devices"-- bike- and scooter-share. But make no mistake--this conversation is about much more than that. City representatives pointed out that they need to create regulations that can give them the ability to oversee and plan whatever new "disruptions" may appear in the future, which may be drones or autonomous vehicles or still-unknown devices.

And they don't want to be caught flat-footed the way they did with ride-hail. Uber and Lyft were able to rapidly deploy their services before cities could anticipate the impacts they might have on traffic, emissions, and safety. Cities have been playing catch-up ever since.

The ride-hail companies also managed to get written into CPUC regulations that they would not have to share their data with cities. The California Public Utilities Commission was given oversight over ride-hail companies mainly for historical reasons; they oversee taxi regulations. Early assumptions were that ride-hail should be regulated in similar ways. A representative from the CPUC was present at yesterday's hearing, and he alluded to a proposal in the works to change data regulations, but that would all be decided in a different venue.

Whatever the legislators decide about bike- and scooter-share data is likely to set precedent for future conversations. Yesterday's hearing, however, was not about making decisions but about airing opinions, of which there were plenty.

Bike-share and scooter companies track their devices, and they collect data on where bike and scooter trips begin, where they end, what route they take, and other personal information about the app users. Cities say they need some of this information to be able to enforce safety and equity rules as well as to plan infrastructure.

For a good background on the work being done at the Los Angeles Department of Transportation on this, and the pushback from Uber, see this recent CityLab deep dive into the subject. The city, in conjunction with other municipalities, has developed its own data analysis system, called MDS, for "mobility data specification," and requires companies that want to deploy devices in the city to provide some of the data they collect. Uber, which owns Jump bikes, has pushed back hard, decrying government overreach and claiming that the data the company collects is not safe if it leaves Uber's hands.

The concern about consumer privacy is a serious one, especially as reports emerge about government agencies such as ICE gaining access to license plate databases, for example. Dr. Matthew Bishop, who heads up the computer security lab at UC Davis, talked about how to "anonymize" data--that is, how to strip out all personal information by suppressing pieces of data like part of a zip code, "perturbing" it by adding extraneous bits of information, or aggregating it into larger pieces that cannot be broken apart. But, he warned, it is still possible to "de-anonymize" data and identify individuals. "You need to design privacy in at the beginning," he said, "not after the fact."

Other topics covered in this somewhat rambling hearing included:

- The need for academic researchers to have good data--which is already being collected by companies--to conduct useful analysis on travel behavior, for example, and why people make the travel mode choices that they do.

- The methods academic researchers use for protecting data from being accessed--for example, kept in a closed system, not downloadable--or monetized.

- Cities' need for data to inform their planning, and how much detail those data bits need to include. Is it enough to have information about where trips begin and end? Does that data need to be current or can it be historical and aggregated with many trips? The answer depends what you need the data to do.

- The notion, developed alongside MDS, that private, third party companies can provide data analysis that cities don't have the people-power to do, and can also act as a cushion between raw data and government agencies, making it harder for unintended release of personally identifiable data.

- Uttara Sivaram, head of privacy and security policy for Uber, delivered a passionate and hyperbolic manifesto on government overreach and incompetence, and on consumers' rights to privacy, saying the L.A.-developed MDS data collection effort--not Uber's own data collection--is "akin to placing a tracking device in [consumers'] pockets. They don't know it's there, and they don't know how their data is being used."

L.A. City Transportation Department (LADOT) General Manager Seleta Reynolds spoke of the "collateral damage" cities had to deal with when ride-hail companies steamrolled into town without asking permission. "At stake is whether government will have a chief role in managing cities, or whether private companies will take over," she said.

She said the data L.A. collects about dockless devices is used "to keep communities safe and to ensure equitable distribution. We absolutely do not collect personal information about riders," and the data they do collect is classified as confidential, with strictly controlled access to it.

"Seven of the eight companies [with permits to operate in L.A.] have complied with our requirements," she said, and since the new rules went into effect "complaints have dropped and the number of rides have been rising."

"There is no way we can run the city without valid information about what's happening on our streets. Private companies are accountable to shareholders, and we are accountable to everyone," she added.

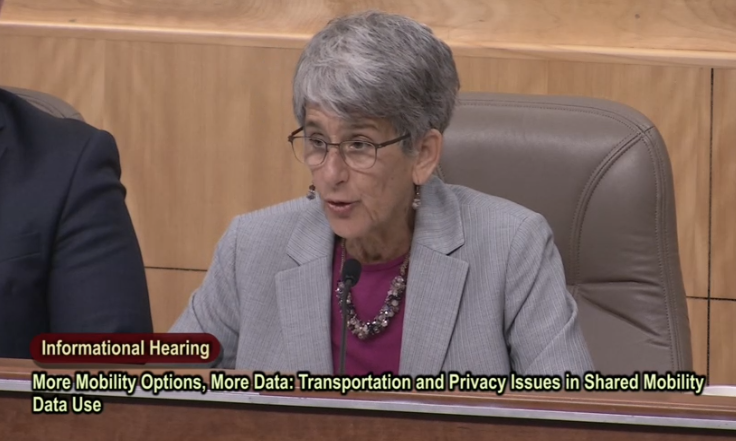

Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson (D-Santa Barbara), chair of the Judiciary Committee, was focused on the need to protect consumer privacy. "We are collecting enormous amounts of data," she said, "and people don't necessarily know their information is being accumulated... Our job as legislators is to provide oversight and safeguard privacy, not only by private companies but also by the government," she said.

The legislature's goal is to "ensure that data is available, but does not place personal information at risk. Location data is sensitive," she said, echoing a common theme in the hearing. "We need to put our foot down and put a stop to reckless dissemination of information in our society."

To Uber's Sivaram, Jackson said, "I'm delighted there's been a turnaround [at Uber] as far as recognizing what is and what is not appropriate, especially when it comes to regulation. Most people get on a scooter and think they're just getting somewhere, but in fact all sorts of data is being collected. We need to narrow what we're looking for; we need to ask people if they want to provide this data. How do we get there?"

Sivaram responded that first it was necessary to determine what goals need to be solved. (Goals mentioned by various people at the hearing include safety, keeping sidewalks cleared, providing adequate infrastructure where it's most needed, having a way to double check that the data coming from the companies is accurate, knowing where people want to park scooters and bikes so spaces and racks can be provided, increasing access to mobility choices in underserved communities, reducing car trips and emissions, and providing data to ask deeper research questions like why people chose the mode they choose or what is holding them back from riding a scooter, for example.)

"Some of those can be answered using aggregated data, and some will require disaggregated data," said Sivaram. "In those cases it's absolutely necessary to allow people to opt out. Giving users more control over what they share is absolutely key," she said.

Assemblymember Laura Friedman (D-Glendale) pointed out that the conversation "about the difference between government and private company collection of data is a mirage. Either we allow it or we do not. Why, philosophically or legally, is private company data collection any different from what a government might also want to understand?"

Sivaram’s response was "purpose limitation."

"We can only use data for the purpose it was collected in the first place," she said. "If we want to offer you a product, for example, we need to ask you. If we don't have a concrete use [for the] data then no, we can't collect that data," she said.

But the opt-in, opt-out question wasn't put to rest. While consumers can opt out of providing personal information on apps, the price of that often is that they don't get to use the app. But in this case, it's not just the use of an app that would be denied--it would mean not having access to clean mobility options that can replace car trips and increase a person's travel options. As Linda Khamoushian of CalBike pointed out, the question that needs to be asked is whether you can still use the device if you opt out of providing personal information.

If California is serious about helping facilitate these mobility options, that's one of many questions that need an answer.