The Senate Governance and Finance and Assembly Transportation Committees held a joint hearing earlier this week to gather information on what the legislature needs to consider as it looks at regulations for the emerging "micromobility" industry.

State legislators hope to avoid repeating mistakes made when ride-hail companies - Uber, Lyft, and the like, known as Transportation Network Companies, or TNCs - suddenly showed up on the scene. The rapid deployment of scooter and bike-share similarly caught cities flat-footed when they arrived a few years ago, but there are differences.

For one thing, the companies have not been able to steamroll their way into the transportation system in the same way Uber did. They tried, but when cities began banning them they realized they would have to find a way to collaborate if they were to survive.

TNCs are for the most part regulated only at the state level--with a few exceptions, such as San Francisco's potential new TNC fee and LAX's attempts to limit where the companies can pick up or drop off passengers. But most of the safety and other regulatory actions happen at the California Public Utilities Commission, which according to Assemblymember Jim Frazier, one of the co-chairs of the hearing, is having a hard time doing its job.

In contrast, most regulations on shared scooters and bike-share are at the local level. According to Juan Matute of UCLA's Institute of Transportation Studies, who provided an introduction to the subject, a few California cities prohibit scooters, some allow them without a formal permit, and many others have created or are in the process of creating a permitting program. Those regulations allow cities to set safety requirements such as hours of operation or speed restrictions, to promote equity by requiring balanced access, and to control the number of devices deployed.

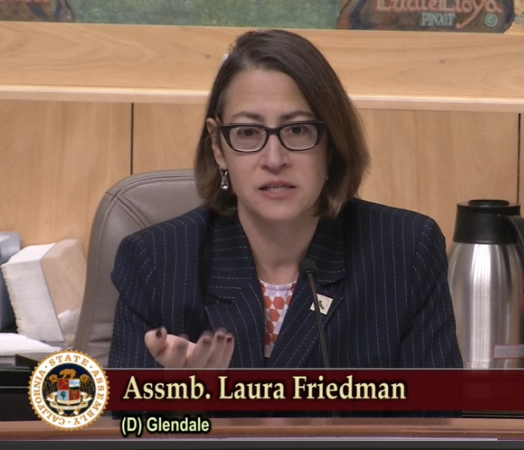

To be enforceable, they require data, an ongoing bone of contention between legislators and all of these companies, including TNCs. L.A. just suspended Uber's permit to operate Jump bikes in the city because Uber refused to provide the city with data. A bill by Assemblymember Laura Friedman, A.B. 1142, would have clarified what data companies need to provide. But that died in committee earlier this year because it was strongly opposed by Bird and Uber.

Data was not supposed to be the subject of this hearing; another joint committee hearing specifically addressing data be held in January. Nevertheless, the subject kept coming up.

The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Authority and the Los Angeles Department of Transportation first provided information about lessons learned from their experience with TNCs, including the severe handicap regulators experienced because the companies refused to share the data they collect. Cities have a hard time seeing, for example, how TNCs contribute to traffic congestion, or where they might be creating hazards via risky behavior at pickups and drop-offs.

Jarvis Murray, who heads the For-Hire Transportation division at LADOT, told legislators that the city has ended up with a two-tiered system and a hodgepodge of regulations because they can regulate taxis but not TNCs. That means they have no control over driver behavior, cannot enforce equitable geographic coverage or ADA access, and "are unable to use that service to help us meet goals on congestion or wheelchair accessibility, and unable to help them in terms of pricing."

Cities are trying to avoid similar chaotic results from scooters and bike-share by finding ways to regulate, but without putting a damper on them. "When scooters showed up, almost overnight we saw a huge adoption" of them, said Seleta Reynolds, head of LADOT. "We saw people starting to use them for the short trips" that comprise over half of all trips in the city, currently mostly done by car. "So we took it as in our interest to make sure these companies could succeed," she said.

The city found that, at first, companies were not responsive to complaints, and were serving high-income neighborhoods but leaving out the lower income areas "where people desperately needed access to transportation."

The city's permit system addressed those problems. "Because we were able to set regulations and get information from the companies, we were able to set a geofence around neighborhoods, measure exactly how much space there was on the sidewalk to safely store the vehicles, and then give each company an allotted budget for number of scooters and bikes in that arena," said Reynolds. "On a daily basis we were able to see who was obeying the rules and who wasn't, and we could hold them accountable. By doing so, we could also build public trust."

But in order to do so, they need data from the companies. "We collect as little information as possible," she said - about six points of data out of more than two dozen that the companies collect. They are trip start, trip end, vehicle ID, trip time, and the size of the fleet in any given location. These are all reported in real time, with the sixth bit of information - route - reported with a delay.

The city does not collect information about riders. What they do collect allows them to plan for infrastructure like bike lanes and parking, and to enforce equity and geographic access rules.

Scooters left blocking sidewalks have been a big source of complaints almost everywhere they've been introduced, and cities have evolved different solutions for it. In San Francisco, every scooter must be locked to something, a regulation which has led to the companies innovating new locking mechanisms. Sacramento has created parking zones by painting them on the ground. "We want to know where the trips are ending so we can put in parking there," said Jennifer Donlon Wyant, of that city's planning department. "It's not rocket science, it's magical: we put in racks, and bikes will migrate to them."

Representatives from the cities at the hearing - Los Angeles, Santa Monica, San Jose, and Sacramento - all agreed that cities need to be able to regulate these devices on a local level to fit the circumstances of individual neighborhoods. "Cities change block by block," said Kevin Hefner of the city of San Jose. "Blanket policies are insufficient."

They also pointed out that the whole "micromobility space" is still evolving. "This is the second set of regulations we've had," said Donlon Wyant of Sacramento's recently instituted permitting system. Companies go out of business or move out of cities. New ones enter.

"Industry is not yet making money; they will also need to change," said Francie Stephan of Santa Monica's planning department. "Right now, no one is looking beyond about 18 to 24 months ahead, because we know regulations and the industry will change again." Her city convened fourteen cities to survey best practices on micromobility regulation, and found "no dominant model."

But there is definitely a role for the state. "What we would love to see in terms of statewide regulation," said Reynolds, "is we see a complete and total vacuum when it comes to regulation of the vehicles themselves. We see companies doing a lot of experimentation with new kinds of vehicles that we've never seen before, and cities at a loss as to how to regulate them."

Another arena several participants pointed out is insurance requirements. "That's something the state has traditionally done, and done a good job of," said Reynolds.

Chris Dolan, Consumer Attorneys of California, was dismissive of the current liability waivers Uber and Bird have their riders sign. "We heard the same arguments from the TNCs - that insurance requirements would stymie the industry, that rules would hold it back," he said. But the strict limit on liability just transfers costs to the state and taxpayers.

"There needs to be a balance, but the consumer can't be left out," he said. "This regulation has to happen at the state level."

"They can't have a free pass if their device catches fire, or the handlebars fall off," he said. "This is an area where the state needs to regulate, cannot abdicate."

Then there is the question of data--to be further discussed at the hearing in January. Assemblymember Friedman made clear that she was frustrated by Bird and Uber 's opposition to her bill last year.

"Cities need data," she said. "They can't plan for them without it. And yet you have fought efforts to have that kind of data provided for cities. I've gotten a lot of concern from your companies about privacy, which is a little ironic."

"What do you think is reasonable for cities to be able to regulate properly and get the best out of your services as possible? What is the line for you?"

"Cities have the right to data from our devices," said Edward Fu of Bird. "At the same time, our riders have a right to privacy."

Alison Grigonis of Uber said that "trip data is personal data" and the company would be okay "with the right data privacy controls."

"We felt we had that in our bill, but you were still opposed," said Friedman, urging the two to discuss the issue further with her.

In her opening statement, Friedman made sure the hearing would stay on point. That is, that state regulation of scooters and bikes needs to recognize that the "things we put on scooters, like safety-- should not be on scooters. Certainly they should be safe, but most safety issues have to do with our planning. We have planned for automobiles over all else, and anything else that moves into that space is at risk."

"One of the highest causes of death of children is being hit by cars, and we don't talk about that, but when we hear that the death rate from scooters - the collision rate is in the single digits - and everyone talks about how dangerous they are; I'm sorry, I'm a lot more afraid for my six-year-old about her encountering a car then her encountering a scooter."

"If we're worried about that, then we have engineering issues that we should [deal with] in terms of our cities to make our roads safer. We need to get people out of cars in our cities, we have to make our streets safer."

"Our questions should be: how do we engineer our streets to make them safer for micromobility and not how do we make micromobility fit into this paradigm where it has to be them versus a car, or them versus a pedestrian."

"That's kind of on us, as people who engineer cities."