Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

One of the arguments against raising the gas tax a few years ago was that, if California were to meet its goal of increasing the portion of electric vehicles on the road, the tax would bring in less money over time. If electric vehicles don't pay for gas, they don't pay taxes on it either. That's why S.B. 1, which raised gas and diesel taxes, included a registration fee adjustment.

Every vehicle owner pays a Transportation Improvement Fee (TIF), which ranges from $25 to $175, depending on the value of the vehicle. And starting in 2020, owners of electric vehicles will begin paying a Road Improvement Fee (RIF) of $100, an amount that was supposed to approach what the average gas car driver pays in gas taxes annually.

Three researchers who have studied the ins and outs of gas taxes for years--Martin Wachs, professor emeritus at the UCLA Luskin Center, Hannah King of UCLA, and Asha Weinstein of the Mineta Institute--have just published a report estimating how much revenue that is likely to be.

Gas and diesel taxes, even at the new higher rates, will bring in less money over time. But even if electric vehicles are adopted at the current lackadaisical rate, the registration fees will largely make up for that loss in revenue.

And if California does reach its goal of five million zero-emission vehicles by 2030, the researchers estimate that revenues will be even higher.

That may seem surprising, since the assumption has been that increased adoption of electric vehicles is a threat to transportation revenue since drivers of those vehicles don't pay gas taxes. But because the TIF is based in part on vehicle value, and new electric vehicles tend to have higher value than gas burners, as more zero-emission vehicles are adopted, TIF revenue will go up.

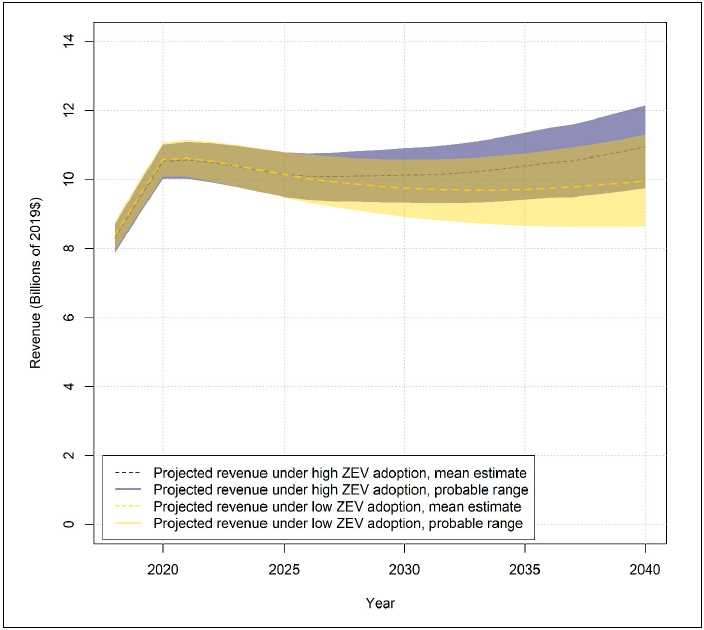

Of course there are a lot of assumptions behind these estimates, from how quickly zero-emission vehicles are adopted to population size and the overall number of vehicles being driven. Other hard-to-guess factors include the fuel efficiency of the overall fleet--especially given current federal resistance to increasing it--the price of gasoline, and how much people will drive.

The researchers used sources such as a national projections from the US Energy Information Administration where they could. Details on their sources and methodology can be found in the report.

They estimate that the $8 billion in revenue collected in 2018, the first year of S.B. 1, will increase to $11 billion by 2020. After that, revenues fall, but they go back up. By 2040, they project $9 billion in revenues in their "low-adoption" scenario and $11 billion under a scenario where California aggressively adopts zero emission vehicles.

The California Transportation Commission continues to explore other ways to raise transportation revenue, such through road-user charges that drivers would pay per mile driven. But this study shows that even without such a system, there will be a continuous source of money to maintain and improve California's highways, streets, and roads--and that it was a very good idea for the legislature to make sure S.B. 1 included a way for electric vehicles to contribute.