Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Canada's Centre for Active Transportation has released a guide for planners on how to better plan for and encourage the integration of bikes, walking, and transit.

This is a topic planners struggle with, as these modes often seem to be competing for limited road space as well as ridership. It doesn't have to be that way. Transportation works better for everyone if the modes are integrated and support each other. That means it is just as important for transit agencies to help make it easy and safe to walk or ride a bike to catch a bus or a train.

But how? Planning is usually mode-specific, with separate teams, separate plans, separate funding, and separate projects designed for each mode. It is not common practice--yet--to think about the ways all these modes work together and to integrate them at the planning stage.

The guide, "Improving Active Transportation and Public Transit Integration," offers a menu of very different "best practices" from cities in Canada and the U.S., describing in detail how they use infrastructure and programming to improve travel for all modes together.

"Given the long-standing axiom that all transit users are pedestrians at some point in their trip," reads the guide,

it would be logical to think of planning for transit as planning for pedestrian and cyclists as well. But, logical as it may seem, taking an integrated approach within our car-dominated cities requires persistence and the forging of alliances. This guide provides a resource to staff at planning and transit agencies, as well as community advocates, to help them make that case. Further, this guide demonstrates the value of including active transportation in transit planning from the very start.

The guide highlights six best practices:

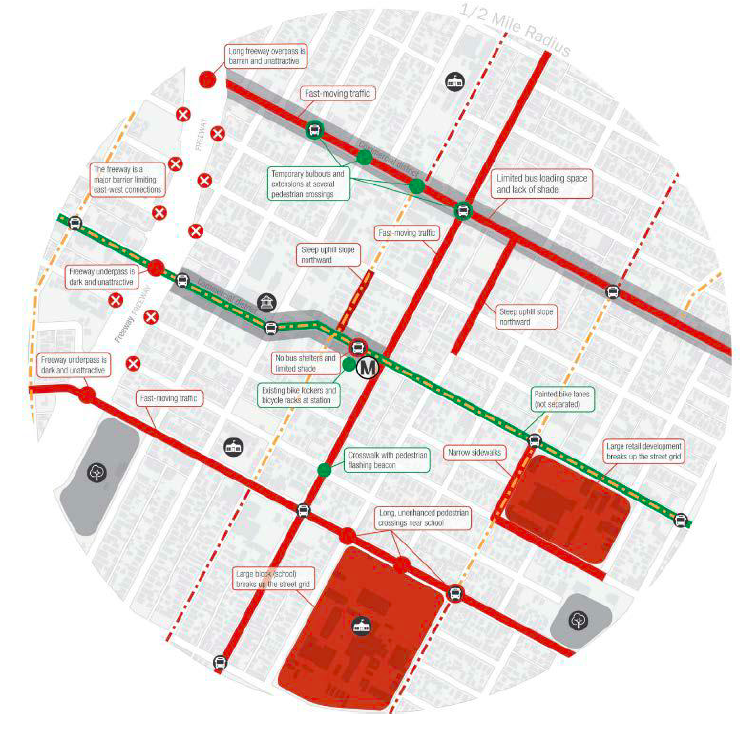

- Undertake system-wide analysis. Improving a single bus stop or crosswalk, or building a short bike lane, will have little effect on overall transportation goals. It's important to start by taking a good look at the existing network.

- Develop specific and detailed plans. Goals are not enough; plans need to identify specific places that need improvement and what improvements are needed, and include estimates of how much they will cost.

- Conduct outreach to riders but also to agency staff. Operators often know what challenges need to be addressed but are not frequently consulted. The guide doesn't say so, but outreach should also include people who might ride transit but don't. The challenges people face--be they cost or distance or time concerns, need to be identified.

- Provide dedicated, predictable, long-term funding. Reliable funding can encourage collaboration and creative problem solving

- Form partnerships, assign clear roles.

- Improve both active transportation and transit at the same time. Large transit projects that involve construction are a good opportunity to improve active transportation simultaneously, and the best outcomes happen when it is integrated from the beginning of the planning process.

Two California examples are offered among the guide's "best practices." L.A. Metro's Active Transportation Strategic Plan outlines a regional network and discusses specific ways to improve walking and biking near transit. And the San Francisco Bay Area's Safe Routes to Transit grant program, funded by tolls on area bridges, helps cities make local improvements that enhance the entire network.

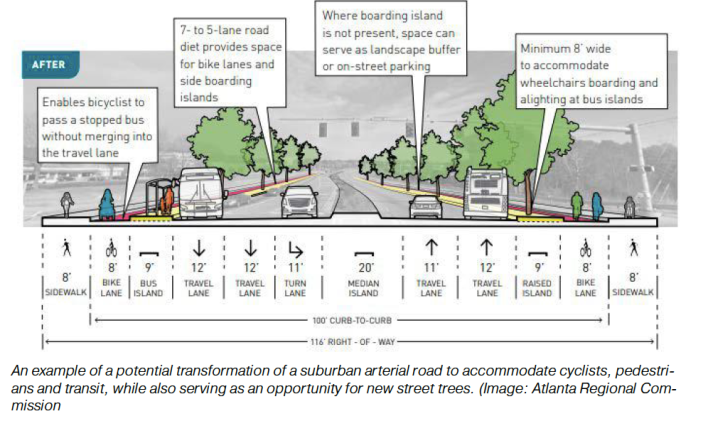

Other best practices discussed--the guide doesn't claim to be comprehensive--include Toronto's GO rail station access plan; Atlanta's "Idea Book" for planners; Vancouver's regional cycling strategy; Denver's bicycle parking plan; and Portland Trimet's detailed plans to improve walking and biking to transit.

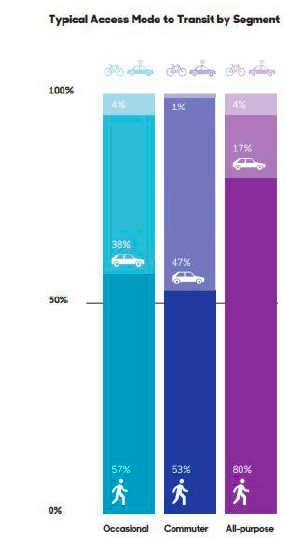

The guide stresses why all of these approaches are needed: research from TransitCenter finds that a majority of people walk to transit in most jurisdictions in both Canada and the United States. "This represents a considerable opportunity for future planning," says the guide. "A number of transit agencies have conducted detailed audits of their transit facilities and the surrounding environment to both diagnose problems and identify opportunities for improvement."

The guide functions almost like its own "idea book" for things that would enhance transit access. They include such details as shade, bike parking, allowing bikes on-board transit vehicles, parking lots that are active transportation-friendly--things that a rider experiences as lacking but relatively few agencies think about or integrate into their stations and stops.

It also, importantly, discusses conflicts between modes--transit and bikes, transit and walking--and ways to prevent them or make them less lethal. Large transit vehicles that have poor visibility can create a hazardous situation for riders. So too can streetcar tracks, which can throw bicyclists onto the ground, and bus stops that are badly located because planners didn't think to survey the context from the perspective of a pedestrian..

This guide should be a beginning textbook for street designers and planners. It contributes to the ongoing nationwide discussion of the importance of complete streets--including a push at the state level in California as well as at the national level--by showing planners and engineers that not only is it crucial to design streets for all users, but it is possible, and is already being done.

"Improving Active Transportation and Public Transit Integration" is available from the Centre for Active Transportation in Toronto.