Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Judging from the opening remarks by Congressman Jeff Denham (R-Turlock), the federal hearing on high-speed rail in California seemed like a set-up for grandstanding hostility. Denham complained of the project's growing price tag, saying its “confusing” business plans “are clearly not grounded in reality.” The original bond measure, he claimed, promised California voters that a high-speed rail connection between Los Angeles and San Francisco would be completed by 2020 and cost only $33 billion. For the record, the bond did not claim it would cost only $33 billion).

“This is a poster child for mismanagement,” he railed. Denham had called for a federal audit of the California High Speed Rail Authority (CAHSRA), he said, because it has consistently missed deadlines and run into cost overruns, changed its plans, and reduced its promised scope of service. “There is no reason to believe that anything with regard to this project will go according to plan.”

“We've got other issues in California,” he said, and “a fraction of [the money invested in high-speed rail] could have solved our water crisis, with the same jobs--some would argue, with more jobs.”

Later in the hearing, Congressman Doug LaMalfa (R-Richvale) expanded on this notion. “We could build twenty dams for the price of what we're spending on high-speed rail,” he said--as if money were the only thing holding California back from building dams everywhere.

But it was clear that other Congressional members on the panel take a slightly different view of state infrastructure investments.

Congressman John Garamendi (D-Davis), while wanting to better understand plans to finance the project, said he was excited about the economic impacts it has already had, including the jobs it has produced. The completion of the first segment in the Central Valley will bring important benefits to communities there, he said.

“California didn't become the fifth largest economy by chance,” he said, pointing to other state investments in infrastructure, transportation, and education. “We've got things to do, places to go, and we need people to build it.”

Brian Kelly, current CEO of CAHSRA and former head of CalSTA, the agency that oversees CAHSRA, gently pointed out that CAHSRA has met all of its federal funding deadlines. And, although funding has not been procured for two of the trickiest (and most expensive) segments, there is enough money to complete several key parts of the ambitious project, with immediate local benefits.

Denham questioned Kelly sharply about the differences between Prop 1A, the voter-approved bond that got high-speed rail project going, and the current business plan. What is the reason for delays, Denham wanted to know, and where will future funding come from?

Kelly started to refer him to Chapter 4 of the CAHSRA business plan, but was interrupted before he could elaborate. “Is it labor?” asked Denham. “No,” said Kelly.

“Is CEQA the holdup? Are we done with environmental review?”

“No, we are not,” said Kelly. “We had some requirements to quickly spend federal dollars, and so got into [early] construction before we had all the right-of-way and third party agreements finished.”

“If the state [can] waive CEQA for stadiums . . . streamlining could be done if this were a real priority,” said Denham. “The rest of the nation would like to hear what you are doing about that.”

Kelly began to respond, but Denham cut him short and moved on. . . to Garamendi, who asked Kelly to finish his response.

Kelly said that the Authority has asked the federal government to assign responsibility for review under NEPA—the National Environmental Policy Act—to California. Because NEPA requires its own process to comply with federal funding rules, agencies are basically forced to go through the environmental review process twice--once for the federal government and once for the state. Giving the state authority to handle the NEPA process at the same time as CEQA could cut the amount of time for review considerably, said Kelly.

Combining NEPA and CEQA has been done, for example, to build highways.

“We have a request before the administration,” said Kelly, “and we're waiting for approval.”

Denham was busy talking to someone else and didn't seem to hear the response.

Under further questioning, Kelly said that financing was and “is the single most important challenge of this project, from day one.” Voters, through Prop 1A, provided $9 billion, which at the time was estimated to be about one-fifth of projected total costs, he said. The original idea was that the federal government would provide about a third of the money, the state about a third, and private investors would kick in the rest.

So far the federal government has contributed about $4 billion, under Obama's stimulus package--nothing has come from the current administration, and Denham has actively opposed any federal money for the project. Private investors won't be expected to come on board until the project has moved further along.

“We are approaching it in a building block way,” said Kelly. “We don't have all the funding right now. Our plan is to use the money we do have to build as much as we can to create a usable service where we can.”

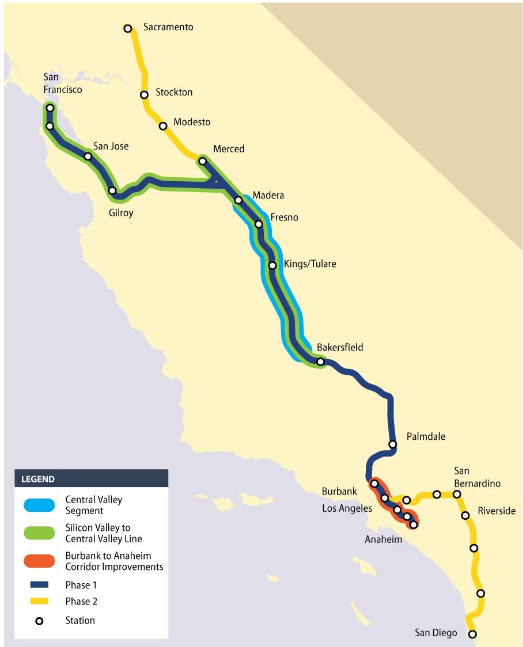

That means focusing on separate segments. The early investments are in the Central Valley, where bridges and viaducts for high-speed rail are already being built; and on “bookend investments” in the Bay Area, where Caltrain is being electrified, with plans to extend service to Gilroy, and in Southern California. There, CAHSRA is partnering with other agencies on upgrades to Union Station and several rail grade separation projects. All of these early investments will bring immediate improvements for local rail transit.

That leaves two remaining, unfunded pieces: a tunnel through the Pacheco pass between the Central Valley and Gilroy and another through the Tehachapis from Bakersfield going south.

Denham and La Malfa tried to drill down into this funding gap, seeing it as a fatal flaw in the project, but others testified that this is a common way to handle large projects. Garamendi pointed out that the President is poised to sign a reauthorization of the National Defense Act, which has no secure funding source for many of its provisions. “It's an ongoing issue, year by year, going forward,” he said.

CAHSRA has estimated that eighty percent of the funding for phase 1—the build-out between L.A. and San Francisco—has already been secured, including federal funds, the Prop 1A bond, and estimated proceeds of about $750 million annually from cap-and-trade. “That's a whole lot better than we're doing for a plan to replace our Navy,” said Garamendi.

Denham wanted to know what kind of leverage the federal government has over the project—what could it do to ensure the state met its obligations, he asked Calvin Scovel, the Inspector General, who is conducting the audit.

The answer was fourfold: the FRA could suspend any as-yet-unspent funds; it could use administrative funds to apply against any missing state match; it could apply the Debt Collection Act of 1982; or it could suspend or debar CAHSRA from participation in any grant programs. “That would require a finding that the Authority was not a responsible agency,” said Scovel.

Mark DeSaulnier (D-Contra Costa) pivoted the question to ask Lou Thompson, Chair of the California High-Speed Rail Peer Review Group, to outline possible actions the state could take.

First, it could just stop now. “And . . . that's not a good idea," agreed DeSaulnier. "What's the next option?”

“They could finish what they're building now—that would protect against any federal claim. It would not provide much value to the state,” said Thompson.

A third option would be to finish work on the “bookend” projects in addition to the Central Valley work, which would bring more benefits, he said. And a fourth option would be “for the legislature and the governor to recommit to the project—to say that we really want to do this, even in the face of uncertainty.”

“That's precisely what the U.S. Congress did on the reauthorization act for the Navy,” said Garamendi. “Even if the money's not there yet, the commitment is.”

And without that commitment, it's hard to manage any large project. “You have to restructure your commitments and take risks you shouldn't have to take," said Thompson. "If the state wants to do this, they should recommit to it.”