Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

After several draft maps, months of outreach, and many public meetings held throughout the nine-county Bay Area, Caltrans District 4 has released its Bike Plan. It focuses on the state highway network, which frequently forms the spine of city main streets throughout the region. That network also frequently poses barriers and obstacles for bike connections, where local networks cross highways, for example, and the point of the plan is to identify those barriers and prioritize solutions.

District 4's Bike Plan is the first comprehensive district-level bike plan produced by Caltrans using the framework of its recently completed statewide bike and pedestrian plan, Towards an Active California. To write it, district staffers looked at where improvements were needed, identified opportunities, gathered public feedback, and analyzed projects to put them in priority order for future planning.

There are some surprising things in the report, especially for people who are used to thinking of Caltrans as an automatic “no” on innovative safety changes. Bulb-outs and bike signals, for example, where bike networks cross busy state highways. A dedicated bikeway along State Highway 123, also known as San Pablo Avenue. The bike lane planned for the Richmond San Rafael Bridge.

Many of these improvements reflect local plans and priorities, although district staff went further to collect input directly from community members in an extensive outreach effort. That meant holding numerous public meetings, conducting an online survey that provided a map on which people could weigh in on gaps and needs, and convening focus groups specifically targeting underrepresented minority or low-income communities. Those were hosted by community organizations who recruited ethnically diverse groups who fit a particular criteria—they were bike riders, members of a low-income community, and dependent on alternative means of transportation, for example.

“We asked about challenges and barriers community members experience to biking, and also asked what things they could see as getting them to bike more,” said Sergio Ruiz, District 4 Pedestrian and Bicycle Coordinator and lead staff on the district plan. “That helped inform the way we prioritized projects.”

The plan prioritizes improvements according to a list of factors: how much existing and potential demand there is for them, the quality of the existing facility, how much of an improvement a proposed project would make, local support, and cost. In addition, if a project would benefit a disadvantaged community, it was bumped up on the priority list. District staff used data from CalEnviroScreen as well as the Metropolitan Transportation Commission's Communities of Concern to determine this last point.

Appendix C of the plan includes a summary and detailed discussion of these various outreach efforts.

Nine counties is a wide, diverse area, and local circumstances, from level of active advocacy to interest from city planners, are very different. Also, the improvements identified in the plan are still conceptual; most projects will require more detailed study, funding, and coordination between local jurisdictions and Caltrans before they can be built.

But this bike plan provides a much-needed guide for where to go next. “It will help inform future Caltrans projects, but it will also help inform local projects, whether through encroachment permits or partnering with local jurisdictions,” said Ruiz. “These projects and the needs analysis will be incorporated whenever work is done on the highways, from resurfacing to upgrading curb ramps. We can look at the work in the plan, where we identify potential barriers, and use that to come up with solutions.”

Just because they are in a bike plan, of course, does not mean the projects are about to be built. But many are in development, said Ruiz. He pointed to a resurfacing project in Sebastopol, which will include green-painted bike lanes. “We partnered with the city to develop a new striping plan throughout downtown Sebastopol,” said Ruiz. “We work with the cities and counties to improve the bike networks,” he said. “We want them to interconnect.”

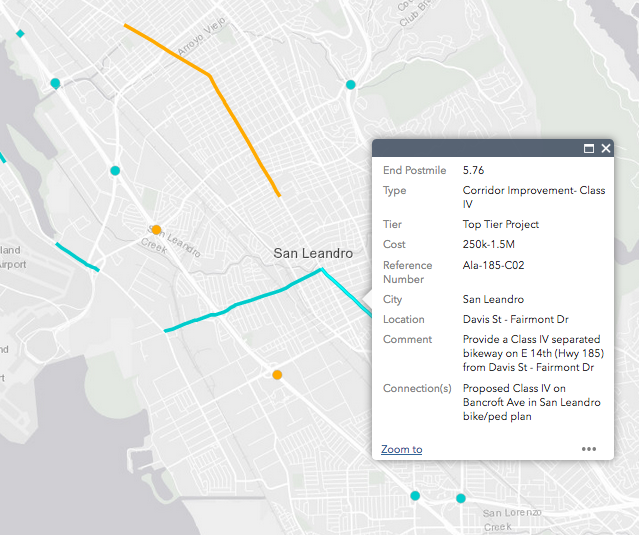

The plan itself contains detailed maps and project lists, which might slow down some computers—but a lower-resolution version is also available. In addition, a separate mapping tool offers a comprehensive interactive map of the projects in the plan. Clicking on specific projects brings up details of those projects, including their extent and whether they came from local city bike plans.

Ruiz says that District 4 is also getting ready to initiate a pedestrian plan later this year. “It will follow the same framework,” he said, “but there will also be differences, because measuring pedestrian needs is a different process.”

Other Caltrans districts do not have comprehensive bike plans like this one. They could do much worse than use this plan as a template. Although, as Ruiz points out, many of the other districts are smaller and have different issues, such as more rural routes, there is still a need to find out what residents in those districts need to be safe and encouraged to get on their bikes.

“Even within our district, not a lot of consistency in the quality of planning at the local level,” said Ruiz. “Some of the areas are doing great work, but other areas not as much, or they have different goals. One of the challenges on this project was bringing it all together, and making it consistent across the region.”