Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

At a hearing yesterday of the Joint Legislative Committee on Climate Change Policies, California Air Resources Board (CARB) chair Mary Nichols celebrated the accomplishments to date of California's efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the state.

She also sounded a few alarm bells about the future of those efforts. “A significant part of [California's] success relies on support from the federal government,” she said, but that support is disappearing. “Every month brings another rollback and increasingly alarming policies that threaten public health and the future of our climate programs,” she said.

“I expect that [California] will continue to lead the way, by providing an example, and driving new technologies, with an eye on decades into the future. But federal actions may undercut our efforts.”

The hearing was held to discuss the recently passed Climate Change Scoping Plan, a document that has been under development by CARB for the last year and some. Nichols characterized support for the plan as “overwhelming,” though she acknowledged that “we have a lot more work ahead of us” to reach ever stricter greenhouse gas reduction targets set by the state.

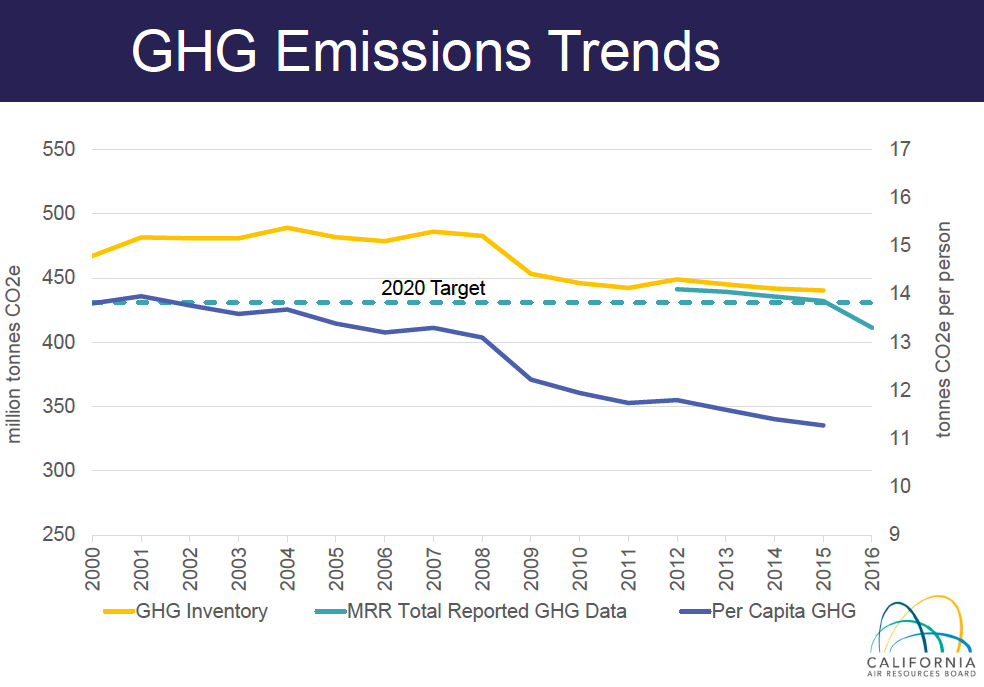

Nichols provided charts showing reduced emissions over time. California's experience, she said, shows that it is possible to cut emissions and grow the economy.

While the state uses a mix of regulations, incentives, and cap-and-trade, the scoping plan largely focuses on the cap-and-trade system, which is a policy still in its proving stages.

Nichols asserted that cap-and-trade, the state's signature policy on reducing carbon, “is an essential component” of California's regulatory approach “because it creates the highest certainty that we will reach our targets at the lowest cost.”

Cap-and-trade sets a cap on industry emissions and auctions off permits to companies for the “right” to pollute up to that cap. It allows industries to buy, hold, and trade those permits, puts a monetary value on emissions and, the hope is, creates a monetary incentive to reduce them.

Nichols talked about the benefits of this market mechanism for reducing carbon: It provides certainty to industries—“As much as that is possible, given uncertainties in economic trends and technology development,” she added—it is a cost effective approach, and it allows California to attract global partners, which is how these efforts will pay off in the long run.

“We will benefit in California both economically and environmentally,” said Nichols, “as our policies are copied elsewhere.”

Also, by raising money, cap-and-trade “provides the benefit of direct investments in disadvantaged communities. It also creates a sustained market signal that helps create stability. Our modeling shows that the cost of other regulatory options is billions of dollars higher, to achieve similar results,” noted Nichols.

However, the largest source of emissions in the state—the transportation sector, which accounts for half of all greenhouse gas emissions in California, and ninety percent of the state's diesel emissions—is harder to tackle, and largely unaddressed by cap-and-trade. The state has so far relied on encouraging new technologies, clean fuels, and sustainable land use planning that can make driving unnecessary.

But the largest of those mobile sources, including trucks, locomotives, and ships, said Nichols, are not subject to CARB's authority because they are regulated by the federal government. And that is a problem, given the current administration's lack of interest in addressing environmental problems.

California is unique because the state has a waiver that allows it to adopt stricter vehicle fuel efficiency standards than federal requirements. Other states have been allowed to follow California's lead and adopt the same standards, but California has been the leader.

“We continue to seek a productive relationship, but the Trump administration may choose not to extend our waivers, or even to attack our authority,” she said. If that happens, “We would fight with every legal and other tool we have at our disposal—but if we were to lose, we would [also] lose significant reductions needed to achieve all our various climate goals.”

The ensuing conversations hinted at the complexities involved in trying to create an entirely new mechanism to shift society away a reliance on polluting industries for economic viability. Ross Brown, discussing a report from the Legislative Analyst's Office, pointed out some of the consequences of the way cap-and-trade allows companies to “bank” allowances for the future. This could affect whether the state's future targets will be met, as it is possible that allowances bought today could be used to sidestep future greenhouse gas reductions.

Committee members and Senators Henry Stern (D-Woodland Hills) and Nancy Skinner (D-Oakland) both expressed concerns about measuring and accounting for unanticipated emissions, such as from wildfires or undetected methane leaks like the one at Aliso Canyon.

Chair Nichols also addressed questions that have been raised by some about whether cap-and-trade will lead to actual in-state pollution reductions. Environmental justice advocates have pointed out that if the state's climate policies allow industries to reduce pollution elsewhere, while not doing anything about local emissions, it could potentially do more harm to California residents than good, despite investments in those communities from cap-and-trade.

Those are legitimate concerns, said Nichols, “but it is true for all our regulatory programs, not just cap-and-trade.” An an example, she pointed to individual air district programs that “reflect local preferences and local circumstances, including feasibility and cost effectiveness” that can lead to widely varying emission levels from facility to facility.

“To address these disparities, we need to look at the regulatory system as a whole,” said Nichols. That would include not only cap-and-trade and other greenhouse gas policies and regulations, but the efforts of local air districts as well. “This has never been done before,” said Nichols.

Nichols had remarked that the recently adopted scoping plan “builds on past scoping plans.” Assemblymember Cristina Garcia (D-Bell Gardens) chair of the Assembly Natural Resources Committee, which co-hosted the hearing, questioned whether that was the right approach.

“Is it fair to continue to build on the same brainwork that has left communities like mine behind?” she asked.

Nichols responded that, when she talks to people in other countries about California's cap-and-trade investments in communities, “They are flabbergasted, and don't know what I'm talking about. They frequently don't know the term 'environmental justice.' That's not to say that we're so brilliant, but we are definitely ahead of other places in terms of thinking how to address climate justice,” she said. “And while money in and of itself is not going to solve all the problems, it is an important component.”

Garcia pressed the point that “over-reliance on cap-and-trade might work for the whole system, but it might leave my community behind.”

Committee Co-chair Eduardo Garcia (D-Coachella) raised a related issue that came to light at a CARB hearing in December. At that meeting, a CARB staffer had asserted that the agency considered cap-and-trade to be a “direct emissions reduction measure.”

Garcia is the author of A.B. 197, a bill that was attached to the one that renewed the cap-and-trade program, S.B. 32. Garcia's bill required CARB to focus on more than just the economics of cap-and-trade when considering emissions reduction regulations. Specifically, CARB was called on to consider “the social costs of the emissions of greenhouse gases,” and to prioritize “emission reduction rules and regulations that result in direct emission reductions at large stationary sources of greenhouse gas emissions sources and direct emission reductions from mobile sources.”

Environmental advocates believed that the wording required more focus on direct regulations on industry, and less on cap-and-trade, which can be gamed by industry and which, they charge, may actually encourage more local emissions. But CARB's assertion in December that they consider cap-and-trade to be a “direct emissions regulation” pulled the rug out from under that assumption.

Nichols was reluctant to get too deeply into the topic. “I know this is a definitional problem,” she said. “I don't want to brush it over, but it's important that we point out that direct emissions reductions occur for various reasons—that is, real emissions are being reduced” from cap-and-trade. Garcia pushed back. In the hearings on A.B. 197, he said, “there was a lot of debate, and the consensus was that cap-and-trade was not to be considered a direct emission reductions tool.”

Nichols responded that CARB has “looked at the language of the statute and we are confident that we are complying with the letter and spirit of A.B. 197.” Garcia gently reminded her that he was one of the authors of the bill, and that he knew what the legislature intended with it.

“I believe that people's principle concern is about health pollutants,” responded Nichols, “and not allowing cap-and-trade to become a tool to allow [industry] to not reduce emissions. We believe that our current emissions programs are adequate, because we are seeing reductions.”

“We will have to find better measures,” she said, not for the first time, since the state's goals grow more stringent over time. “But,” she said, “we don't think cap-and-trade is either the cause or the cure for that.”