It started as a rhetorical question meant to mock people who believe our country made a mistake on many levels by overbuilding its freeway network and morphed into the basis of current USDOT policy that seeks to defund any transportation program or project that doesn't prioritize automobile and oil dependence: "How can a highway be racist?"

A new report by UCLA’s Institute of Transportation Studies answers that question conclusively by examining the legacy of California’s freeway construction. The report illustrates that the state’s highway network—much of it built in the 1960s—inflicted deep and measurable harm on low-income residents and communities of color.

Using a mix of quantitative data analysis and detailed qualitative research, the study traces how major freeway projects reshaped neighborhoods in Pasadena, Pacoima (in Los Angeles), Sacramento, and San José, documenting patterns of displacement, environmental burden, and long-term community disruption. The four case studies, spanning both inner-city districts and suburban edges of growing cities, underscore how these impacts were neither isolated nor accidental, but systemic across California’s urban landscape.

Demolition and displacement were the most visible and immediate effects of the freeways, but toxic pollution, noise, economic decline, and stigmatization remained long after. In suburban areas, white, affluent interests often succeeded in pushing freeways to more powerless neighborhoods. Massive roadway construction complemented other destructive governmental actions such as urban renewal and redlining. Freeways and suburbanization were key components in the creation of a spatial mismatch between jobs and housing for people of color, with few transportation options to overcome it. Understanding the history of racism in freeway development can inform restorative justice in these areas.

- abstract from The Implications of Freeway Siting in California

UCLA didn’t just prepare a report, but used this research to compile a series of journal articles, policy briefs and reports, all collated at one website. The policy briefs and story maps expand on the work done in the main report, discussing how freeways impacted smaller cities such as Fresno, Colton, or Stockton.

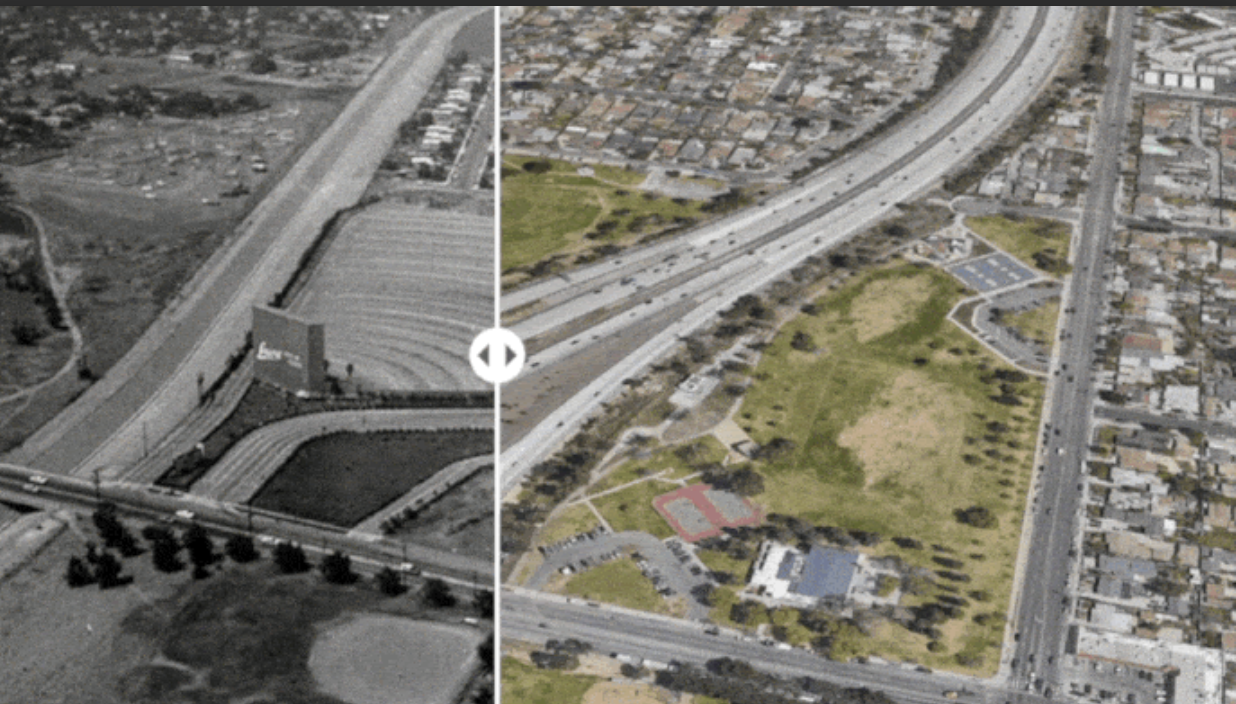

Whether discussing the ways the California Crosstown Freeway (State Route 4) sliced Chinatown, Japantown, and Little Manila in Stockton or how the Simi Freeway (State Route 118) demolished over 1,200 homes in Pacoima; the stories are all similar but different. But sadly these types of projects didn't end in the 20th century.

Knowing the extent of this damaging legacy doesn't mean it's easy to make changes. Historians, sociologists, and advocates have known how highways damage and destroy communities, yet roads continue to be widened or built through communities, and housing is seized and destroyed through eminent domain. And this doesn't just happen in middle America or red states, it happens here, in California.

At Streetsblog Los Angeles, Joe Linton has extensively documented Los Angeles Metro and Caltrans' present day push to widen freeways. Several recent freeway expansion projects, many completed during the last half-decade, erased swaths of Southern California neighborhoods.

Communities are resisting highway expansion. After decades of struggle, Metro canceled planned lower 710 Freeway widening that had been slated to demolish scores of homes/businesses in Latino and Black neighborhoods. Announced by Metro in 2020, one egregious widening was slated to take out hundreds of homes/apartments in predominantly Latino neighborhoods. While Metro eventually pledged to find a way to construct the highway widening without taking homes, it was only after a herculean campaign by local advocates.