A new analysis of the costs of not helping Bay Area public transportation agencies fill a $2.5 billion funding gap found that it would cost former riders twice that much - $5 billion - in annual car ownership costs alone over the next five years. That's not even accounting for the climate, congestion, and emission costs from that many more cars on the road.

And that's just in the San Francisco Bay Area.

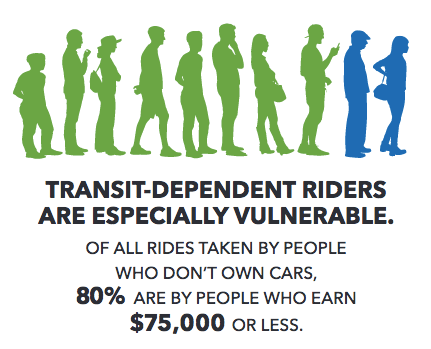

Those costs would also fall on people who can least afford it - and many would just not be able to front the costs of buying a vehicle to begin with. And those who cannot do so, for a myriad of reasons, would be left in the lurch.

Most transit agencies rely heavily on fare revenue, and all suffered significant recent decreases in ridership numbers, which have not yet recovered to pre-pandemic levels. In the Bay Area, agencies are projecting a $2.5 billion shortfall starting in 2025. Without intervention they will be forced to cut services.

But cutting services would lead to further ridership losses as bus and trains become less convenient and less useful for the riders who depend them. Warnings about this "fiscal cliff" and the "death spiral" it could lead to have been raised with increasing urgency as the state goes into its budget negotiations. Now TransForm, a Bay Area transportation and land use think tank, has done an analysis to see exactly what could happen to Bay Area transit agencies in this worst-case scenario.

TransForm's analysis estimates that in the Bay Area alone, there would be 735 million fewer transit rides taken over five years if services had to be cut. This is based on projections from agency Short Range Transit Plans. Many, thought not all, of those shifted trips would be taken by car. Using data from a 2021 report from the National Academy of Sciences and the Transportation Research Board, TransForm estimates that around 33 percent of those rides would shift to drive alone, ride-hail, taxi, or carpool.

That would lead to an increase of 140 million miles driven, or about 35 million new car trips.

"If the state doesn’t step up to fund operations, the cost will be transferred onto the shoulders of everyday transit riders, particularly riders who can least afford it," concludes TransForm.

That could mean higher costs in terms of fares, but it's more than that. Less service would make it even harder to get to appointments and jobs. Pressure to buy cars will grow, but private vehicles are a huge expense, both for the upfront purchase cost, plus ongoing costs to run and maintain. Average annual costs of owning a car is $10,000, a prohibitive cost for many.

"Former transit riders [would] spend nearly $1 billion annually on a mode of transportation that should be on its way out," writes TransForm.

If the state declines to provide funding to help cover the $2.5 billion shortfall, it would end up costing society - and a lot of individuals - at least $5 billion in direct costs, plus the additional un-estimated costs of higher emissions, negative health, safety, and environmental outcomes, and increased congestion.

That is, it would be cheaper to save transit than to let it fail.