Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

For three days, government agency planners and advocates have been listening in to the Active Transportation Symposium, presented by the California Active Transportation Resource Center and Sacramento State. The goal of the symposium was to bring together planners, advocates, and others working on active transportation to compare notes, discuss successes and lessons learned, and update each other on progress in planning for the future of biking and walking in the state.

One major thread woven into just about every presentation is a sticking point for all planning projects, not just ones focused on active transportation, and yet projects looking to make the kinds of changes that bike and pedestrian projects bring must deal with it. That is: the disconnect and faulty communications between planners and the people who are most affected by the projects they build.

The point was made repeatedly: People know what they want their communities to be like, and they have a vision for how to get there, and they frequently know what solutions would work best for them. But between the obscure way planning processes work, planners not understanding how to "reach out" to communities, and the habit of using feedback as a data point to bolster already-made plans, the concept of "garnering public feedback" needs a deep rethink.

That is, planners need to do more than ask community-based organizations to hook them up with residents, more than pay people for the time they spend giving input on projects. They need to learn to listen with respect to what people say their needs are, and be clear about how their viewpoints will be reflected in plans and processes going forward.

This point was made in the kick-off presentation from Monique López, Founder of Pueblo Planning, and it was repeated and expanded on by many of the presenters, some of them planners who have found ways to incorporate some of Lopez's principles into their work. It was also reinforced by the symposium's last speaker, Dr. Destiny Thomas, whose short discussion on shifting planning narratives to address past harms - among other topics - was tacked on to the end of the last session, about bicycle highways, yet was very much on point.

This is the second symposium presented by the ATRC. The first of what they hope to make a biannual series took place in person, pre-COVID, and really was an opportunity for people working in active transportation to meet and discuss topics relevant to their work, and to compare notes. Doing it online is always going to be more difficult, although the sponsors did their best, even including a networking session towards the end for people to break into groups and talk.

While talking over Zoom will always be too contained and limited to offer much spontaneous interaction, the symposium did offer plenty of food for thought for planners, from those who are just beginning to learn about active transportation to people who have been working in the field for years.

Symposium topics ranged from bicycle and pedestrian safety, considerations and opportunities for quick build projects, building strong community relationships, the work being done at state and local levels on conceptualizing "bicycle highways," and connecting to transit.

And building community connections. López talked about growing up in Imperial County, where they saw firsthand how planners let themselves off the hook with minimal public outreach on a waste incineration plant. López recounted how difficult it was for residents to even find out about the plant - even though it had been on the books for years.

"Communities have a vision about what they want their community to be like," they said. "But planning processes are set up for disconnection." In the end, López helped organize and pass a ballot initiative to keep waste incinerators out of Imperial County, thus mooting the issue in this case.

Seeing that "planners are doing things behind the scenes, leaving my community out of the decision-making process," and wanting to know more about their role, López went back to school. What they discovered was that "it doesn't have to be that difficult to facilitate a community's vision."

Now López works as a "connector," helping create and maintain relationships "between those that are in the position of making budgetary or policy or programmatic decisions and the community, particularly communities that are often left out of these processes."

One problem with the old way of doing outreach, López said, was that although planners have discovered that they need to bring in community-based organizations who know the people living in the areas affected by their plans, they frequently don't follow through very well. "Planners would ask CBOs to come to meetings, but people would not be told how their input was going to be used, or even get copies of the final reports," said López. "The outreach process can be very exploitative in that way."

López offered a list of things for planners to consider when setting out on a project: Build relationships, repair past harms, respect community members by listening deeply and communicating clearly, and make the process reciprocal. That is, don't just grab people's opinions via survey and use the answers as data points.

You have to make sure you speak with and plan for the people who will be most impacted by changes, who are usually the most vulnerable among residents. These are frequently Black, indigenous, and people of color, low-income people, queer and trans people, unhoused people, and people living with disabilities.

López pointed to the importance of adopting Targeted Universalism: For example, if planners have a universal goal of improving walking and biking, if they focus only on the people who tend to speak up, or who are the easiest to reach - or even just the majority - they will only improve circumstances for a subset of people. But if they center the needs of the most vulnerable people, they will improve walking and biking for everybody.

"We see our role as facilitators, as ensuring places of healing," López said. "We don't force people to understand or utilize the technical language of planning; instead we facilitate storytelling and art-making for people to communicate their lived experience, their vision, and the strategies they know will solve problems."

Planners "also must ensure that, as we write planning documents, we acknowledge the harm that has been done and may still be happening, and ensure that every solution [incorporated into plans] will repair these harms," López added.

Similar notes were sounded in many of the other symposium sessions, including one from former Streetsblog USA editor Angie Schmitt's, author of Right of Way: Race, Class, and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America.

Although the mainstream narrative about pedestrian safety tends to focus on "distracted pedestrians" who are looking at their cell phones, she said, those are not actually the people most at risk of being killed for walking. Instead, Native Americans, Black people, seniors, and people who live in low-income neighborhoods all have a much higher risk of being it by drivers. "These are not the people we center our safety discussions around," she said. But they should be.

In the U.S. history of planning, car drivers have been at the center, and without any real discussion about what are streets for, or about who has a place in the streets, they have become relegated to vehicles, with other users shunted off to the margins.

"People on the ground understand what the issues are," she said, "but are used to not being listened to. Planners need to listen to people."

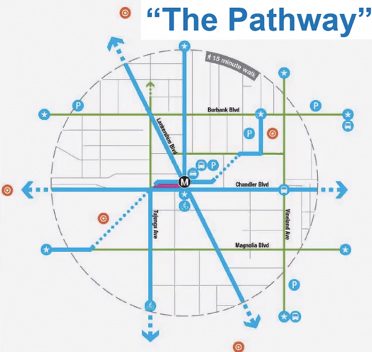

Many of the other presenters, whether planners engaged in conceptualizing bike highways or facilitating bike and pedestrian projects on the ground, made similar comments. "It's a constant challenge: we want the process and the project to reflect the needs and desire of people who live here," said Brent Pearse, of the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, about San Jose's Bicycle Highways program. "We can't do it on our own."

It's a theme that will continue to be raised as state agencies make progress on investing in and uplifting active transportation modes, from Caltrans to CalSTA. For example, the California Transportation Commission's Equity Advisory Roundtable is meeting as this post is being written.

Building strong community relationships was far from the only theme at the symposium, however. Informative sessions included: discussions of successful Active Transportation Program grant applicants - such as the nine-year, ever-improving process undergone by the Yurok tribe at Happy Camp that finally culminated in a $10 million grant to calm a local highway; work being done at the state and local levels to connect transit and bike networks; how Oakland has been able to incorporate inexpensive materials into its planning process to get things built quickly, provide opportunities to test concepts and improve plans before final implementation, and improve communications across departments. There was even an appearance by Mr. Barricade - er, Vignesh Swaminathan - who discussed some of the work he has done on protected bike lane projects, incorporating important drainage considerations as well as safety.

For a list of presentation topics, check the ATRC website, here. All of the sessions were recorded and will be available some time next week at that site.