Streetsblog recently joined BikeTalk and the California Bicycle Coalition in a conversation with new Deputy Director of Planning and Modal Programs at Caltrans, Jeanie Ward-Waller, about changes and challenges at Caltrans. Below is an edited version highlighting some of what we talked about; listen to the entire conversation at BikeTalk.

Ward-Waller has been working for Caltrans for four years. Her background is as a structural engineer, but before joining Caltrans she had worked as an advocate for safe streets with Safe Routes to Schools and as Policy Director for the California Bicycle Coalition, under Executive Director Dave Snyder. She talked about some of the changes happening at Caltrans, in the statewide office, and work that has been started there to support safe and healthy transportation modes.

Ward-Waller started by describing her career trajectory. As an engineer, she said, she had been focused on the work in front of her.

"When you're on the job, you're just thinking about this one project, and you've got a very specific role. I've got to make this building stand up; I've got to figure out what each beam and column looks like and what loads it's gonna see throughout its life. And you never think about the larger implications of it, like: is this the right building to build in this location in the first place? Obviously that's the job of city planners and architects and developers, but I found I was interested in those issues."

She also found that the ethics of the engineering decisions being made about infrastructure projects was rarely addressed by the engineers themselves. They were busy solving technical problems, and left ethical and climate concerns up to someone else. But "we can't not think about those bigger issues, of the downstream effects, the unintended consequences of the decisions we're making," said Ward-Waller.

Snyder remembers being impressed when he met her, he said. "I remember you saying that you had learned how to build bridges, and how to build roads, and that you wanted to change your focus to helping us decide what we should build in the first place. I was thinking: yeah - exactly! And really glad that someone with your skills and intellect and training wanted to join us as as the group of people who were trying to change what the engineers built, rather than just, you know, building. "

"And look at you now," he said.

Ward-Waller is heading up the Caltrans division that oversees planning as well as all programs outside of highways. The new position resulted in part from a push to change the culture at Caltrans from a "hidebound bureaucracy" to one that recognized California is changing and has transportation needs that aren't being addressed. That push led to a new strategic plan in 2015, which Ward-Waller described as bringing "a huge sea change" to the department.

"It takes a long time for it to get from acknowledging at that strategic policy level that these are issues that we care about, to actually building it into everything we do, institutionalizing it, and making it part of the culture," she said. "It takes a really long time to change all of our practices and procedures and ways of doing business, but I've been at Caltrans now four years, and I've seen a huge shift in my time."

Snyder asked about the contrast between her role as an advocate at Safe Routes and CalBike and her current one at Caltrans. "When you were working with the advocates, you had no constraints with regards to what authority you had to push for solutions. You could push for the exact right answer and the exact right process; the constraint was that you weren't in charge of the final decision, you could only influence decision makers. But now you're a decision maker. And yet Caltrans still doesn't have the perfect process, you're still expanding highways and stuff like that. You have more authority, but you can't turn the ship around immediately. Why does it take so long?" he asked.

The constraints are many, acknowledged Ward-Waller, but "this goes for all of us, frankly," she said. "Even as an advocate, while I could have a lot of authority over my own ability to advocate and the things that I wanted to focus on, I still had to work with coalitions of other advocates. You build power in coalition, so you're always working towards compromise in terms of what your priorities are and where you push and where you get a big group to work together to push collectively."

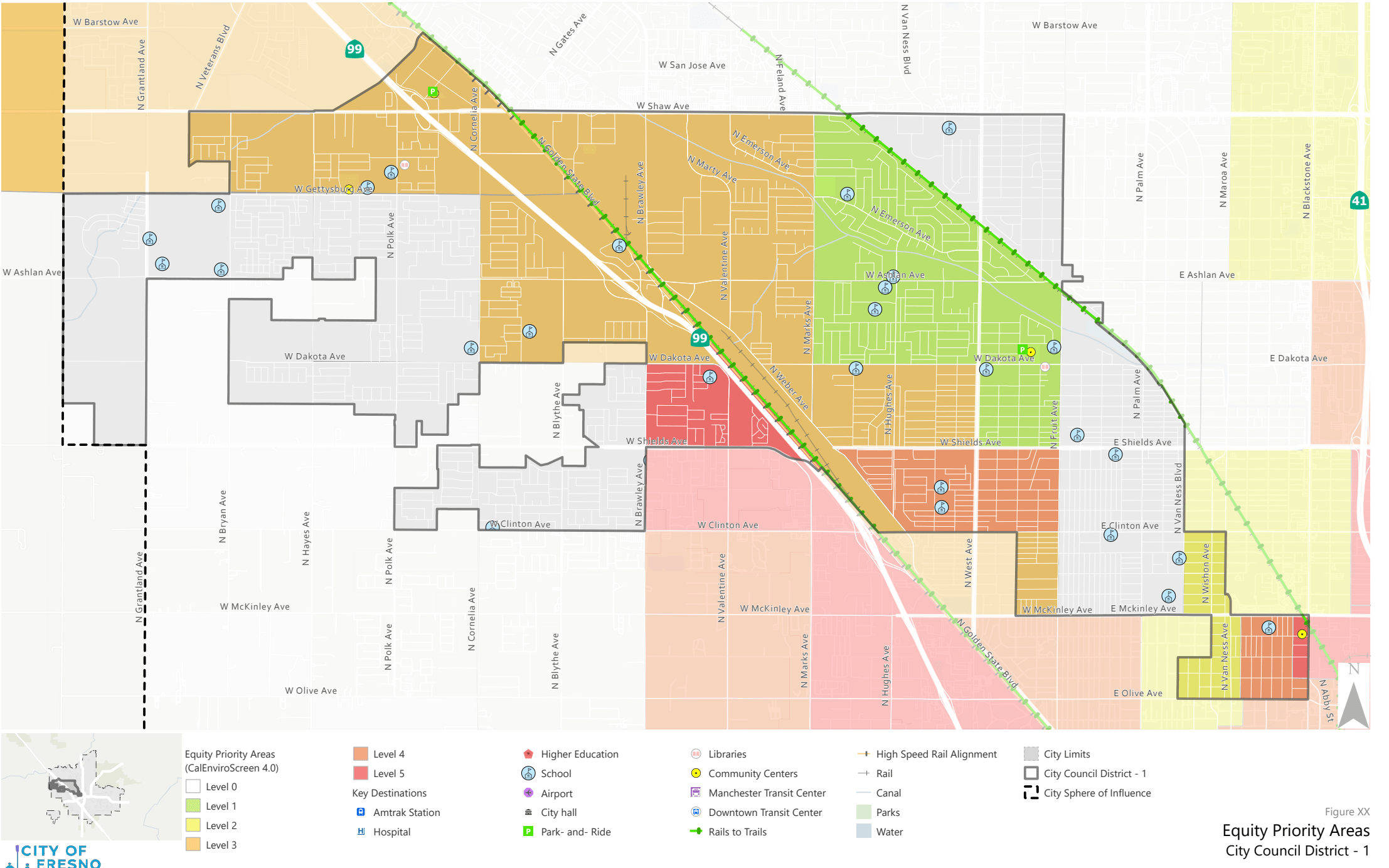

"At Caltrans, yes, I'm in an influential position now, which is just terrific... but I still have to work with all those same different stakeholders. And we're trying really hard to expand the stakeholders that we work with, and the folks that we reach out to and listen to. Equity is a huge priority for us right now, so figuring out how we reach underserved communities and understand their needs better and make sure that that's a big part of how we're doing our work differently is important."

"I also have to work with an executive board; I'm only one member, and we have 25 or 30 people on our executive board, including twelve district directors. I'm just one of many decision makers and we're still building compromise and working towards solutions that work collectively. And that's not even to mention, we report to the governor's office, we are given our authority by the legislature, we operate under the oversight of the Transportation Commission - and their decisions, particularly around what gets funded, really influence our decisions."

"And then of course you know we have partners all across the state. We own the state highway system but the state highway system runs through cities and counties and regions, and all of those partners and the decisions they're making about what they'd like to see on our system also plays a big, big part."

"We're making a lot of changes, but a lot of those changes still are just institutional policies and procedures that take time to manifest in projects. Projects take, in some cases, decades to plan, from inception and an idea through construction. We're trying to be more nimble, to find ways to do things like quick builds, and implement more changes to the roadway. Some changes can be done through routine maintenance - that is an opportunity to restripe and make changes more quickly. So we're looking for those opportunities."

But what about the so-called "legacy projects" that have been in the pipeline for years? Caltrans and its local partners are still planning and constructing highway widenings and removing housing, and those projects are ostensibly being built to ease traffic for drivers but do little to benefit the communities they go through - especially the people who are displaced.

"There's a good reason that some of those projects are in the works... it does take a long time to build big infrastructure, and sometimes you really do need to replace or rethink what a roadway is going to look like," said Ward-Waller. "We need to take time to do that; we need to talk to the communities; and pulling the funding together that takes years and years. So we need to do good planning work, and often that will take a long time to result in an actual project - and we should be looking critically at every decision that we make, through the lens of our policy priorities today, and where we know we need to go in the future."

Then there are all the plans: highway plans, state route plans, "non-motorized" plans that are being transformed into active transportation plans. Some of these are updated every quarter but some, especially in rural areas, don't get updated very often. There are a lot of plans "on the books" to widen rural routes to make them high-speed high-capacity routes. Ward-Waller said that Caltrans is leading "serious conversations" about retiring some of these, but completely redoing plans takes time.

"We're creating what we now call 'comprehensive multimodal corridor plans' so you're thinking not just about the state highway - you know, from edge of right of way to edge of right of way - but 'let's treat this as a corridor, including adjacent rail or transit, adjacent local roads, and in a lot of cases, even including the land use adjacent to the roadway.' This is a new thing for us to be thinking about: what are the land uses that folks are actually trying to access in this quarter? But it's so important."

That means considering a wide range of potential solutions that may not have been tried before on the state highway system, like managed lanes or transit-only lanes, or pricing - or just running more transit. "That's one way to get a lot more capacity out of the road without widening it," said Ward-Waller.

"In some cases it's just totally unrealistic to add capacity to the existing roadway, so the question is: how can we do more adjacent to the highway? Bikeways are certainly one option; running more transit on the local street; just improving connections across our facility could potentially take traffic off the highway in a lot of cases. Ultimately that will result in a lot of those projects looking very differently, so those conversations are happening today. Again, it takes time, because it's not just for us to decide; we have to work with the community, with the local and regional agency; we have to build consensus around what we want to do in those locations. And that's really important."

"Bringing a community that's most impacted by that project or by that corridor into the conversation is one of my biggest priorities right now. Making sure that we are making those decisions and hearing about the needs of the communities that have been most impacted by our facilities, I think, is critical."

There's more in the podcast. For example, Snyder grilled Ward-Waller about California's outdated design guidance, which requires onerous exemptions to do some things - like make lanes narrower - that national standards allow. Ward-Waller agreed that work being done at the national level to update safe road design guidance does not need to be repeated at the state level. This is especially the case because Caltrans leaders are involved in that national work.