Cities might soon get federal money to tear down inner-city highways that federal dollars built in the first place — and use that money to reinvest in communities of color that those highways destroyed.

Shortly before the holiday recess, then-Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer and a coalition of 25 Democratic senators introduced a $435 billion economic justice bill called S5065 that included a $10-billion pilot program aimed at helping communities tear down urban highways, and rebuild the surrounding neighborhoods with the needs of underserved communities in mind. The Restoring Neighborhoods and Strengthening Communities Program — known among advocates as the "Highways to Boulevards" initiative — would only be available for projects located in regions with a high concentration of low income residents or residents of color.

Perhaps most critically, the initiative would make significant funds available specifically for the "community engagement and capacity building" necessary to identify what underserved residents actually want to do with all the valuable land freed up when freeways are torn down. Such funds are rarely the focus of federal transportation grants, which typically prioritize hard construction costs over the dignity of the surrounding community.

"There’s already funding available for highway deconstruction in various other pots of money at the Department of Transportation, especially as so many of our highways reach the end of their life," said Lynn Richards, president and CEO of the Congress for the New Urbanism, which collaborated on the writing of the bill. "And of course, there always seems to be money for highway construction. What there's almost no money for are for the feasibility studies, the capacity building, and the coalition building with the people who are actually impacted by highway projects — or by highway removal projects. That's what's really special about this bill."

Unlike the Federal Highway Act of 1956, which essentially handed communities 90 percent of the money they needed to build freeways wherever they wanted — even when (or perhaps because) they destroyed Black neighborhoods with that money — the new program will strive to ensure that Highways to Boulevards projects are undertaken at a community’s discretion. Funds from the pilot can be used for bike lanes, sidewalks, transit improvements, and basically any transportation project that "doesn't increase net capacity for vehicular travel."

Critically, it can also be used to establish community land trusts, which can generate money for anti-displacement measures that ensure long-term residents can remain and reap the economic benefits of having their neighborhoods transformed into human-centered places. (Other advocacy groups, like Transportation for America, have heralded community land trusts as an essential companion to tear-down grants.)

"If you just provide money for highway removal, you’re just repeating the mistakes of the past," Richards emphasizes. "The last thing you want is a bunch of outsiders coming and saying, 'We’re going to do this, and we don't care what the neighbors want.'"

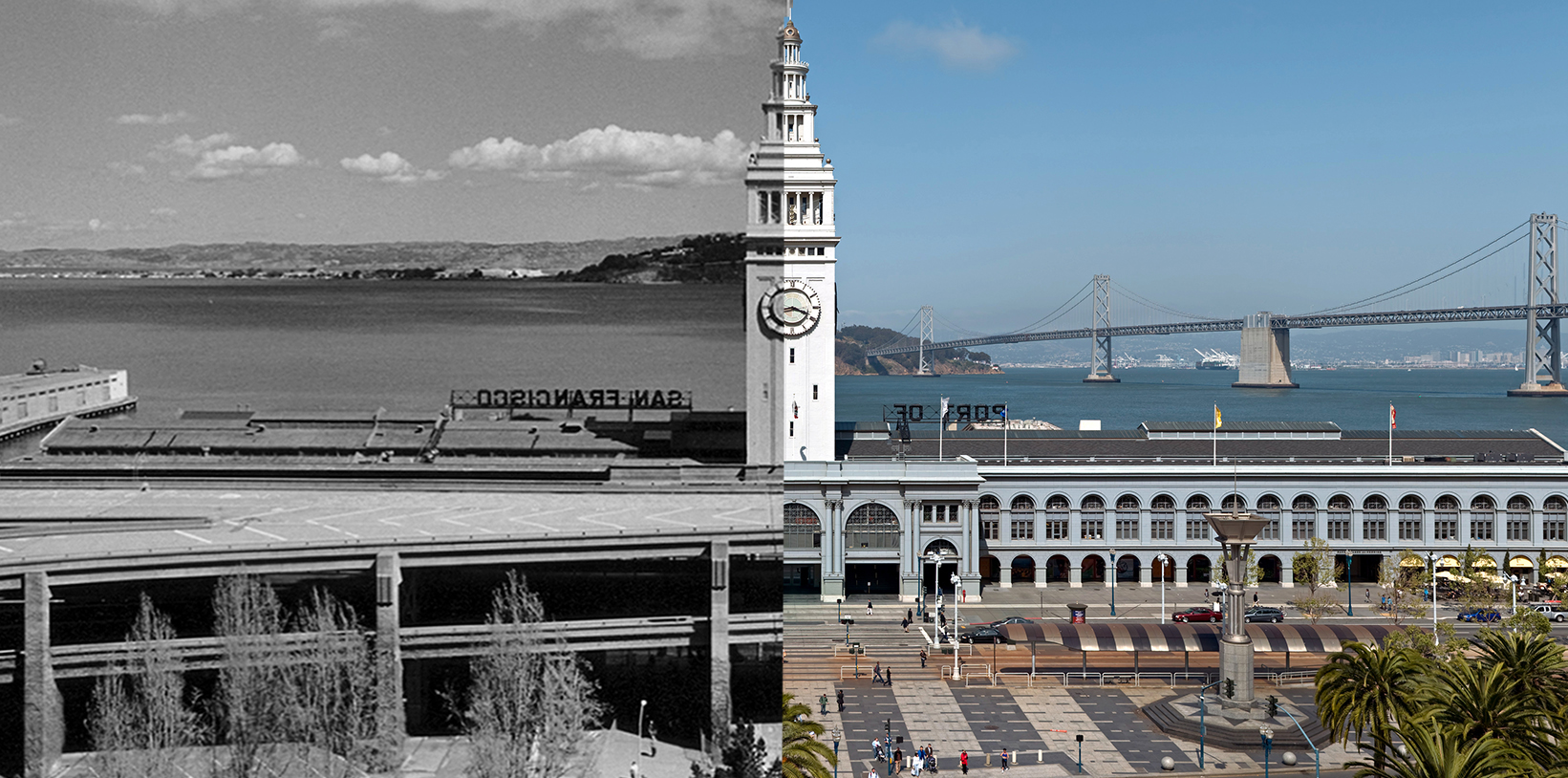

The concept of removing downtown highways isn't new, even if such projects have struggled to secure federal dollars. At least 18 American cities have done it, and advocates are fighting for their state and local leaders to consider their own teardowns as an alternative to replacing the countless crumbling roads and bridges that groups like the American Society of Civil Engineers say are a looming threat to public safety.

"We’ve kind of put a Band-Aid on a lot of these highways, and a lot of them are well past their 50-year lifespan," said Ben Crowther, program manager for CNU's Highways to Boulevards effort. "And a lot of communities just don't want to keep repairing them. ... I can’t think of a single time it has cost more for a community to remove an aging highway than to rebuild it."

And the benefits of rebuilding are negligible at best. Countless studies have confirmed that adding or maintaining urban highway capacity has only a negligible impact on commute times, and those few saved minutes often come at steep costs for communities of color.

"A downtown highway is barely an asset, and virtually all its benefits come at someone else's expense," Crowther stresses. "This isn’t even about removing an entire highway. We’re looking at a one- or two-mile section of the highway — the ones that run through these dense urban areas, where they tend to burden minority communities with pollution, noise and crashes. And they aren't even key nodes. They’re spur highways, stub highways — highways that lead into cities into urban downtowns, and don't always even move a lot of people. "

The incoming Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg seems eager to push highway teardowns. In a statement on Twitter just two days before the Highways to Boulevard program was introduced, he pledged to make "righting these wrongs" wrought by the last century's racist transportation planning "an imperative" of his stewardship of U.S. DOT. His office would be directly responsible for administering the new discretionary grants.

Black and brown neighborhoods have been disproportionately divided by highway projects or left isolated by the lack of adequate transit and transportation resources.

— Pete Buttigieg (@PeteButtigieg) December 20, 2020

In the Biden-Harris administration, we will make righting these wrongs an imperative.

Before that happens, the larger bill that contains the Highways to Boulevards program will need to pass the Senate Committee on Finance, as well as the Senate at large. But with the leading sponsor of the bill poised to become the Senate majority leader — and especially if it receives robust advocate support — Richards is optimistic about the future.

"I'm doing a little bit of a happy dance," she said. "I really think it could happen."