Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Speaking to a room full of student engineers at UC Davis, epidemiologist and researcher Neil Maizlish said that health benefits from Californians shifting from car trips to active modes of transportation could be huge. Most of that would come from reducing chronic disease as people increase activity levels.

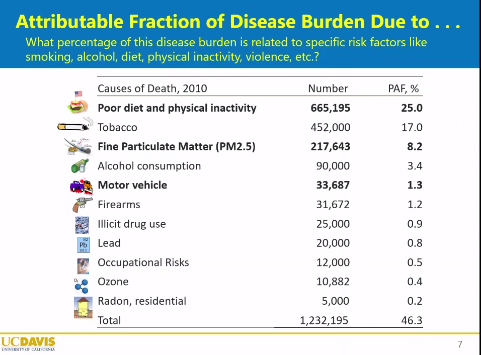

The vast majority of the public health "burden" -- the health problems that cause mortality and disability and cost society money -- are chronic diseases, he said. These are things like heart disease and diabetes, and they are attributable, in part, to lack of exercise -- which means they can be prevented and reduced by increasing regular daily activity, like walking.

This might be the biggest way cars are killing us. Rising crash rates, air pollution, and climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions are a big concern, but according to Maizlish, their health effects are dwarfed by the inactivity we endure when the norm is to hop into a car for all travel.

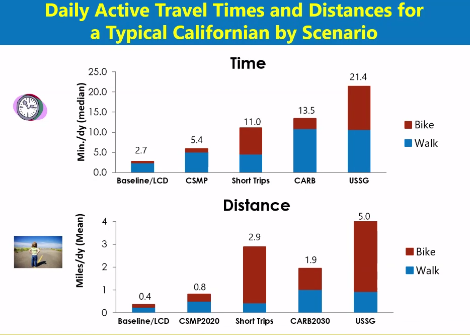

Various agencies have set mode shift goals to reduce driving. Caltrans, for example, has a stated goal of tripling bike trips and doubling walk and transit trips by 2020 (hey, Caltrans, your deadline approacheth). Each regional Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) writes a Sustainable Communities Strategy with goals for shifting people out of cars; the Air Resources Board's 2017 Scoping Plan calls for quadrupling walking and transit trips and a ninefold increase in biking; the American Surgeon General recommends a minimum of two and a half hours of weekly active movement.

ITHIM, the Integrated Transport Health Impact Model Maizlish was talking about, uses these goals and recommendations as potential scenarios for travel. It estimates what would happen if half of the short car trips now made were done by walking or cycling, or if travel didn't change, but all vehicles were suddenly low carbon or zero emission. It calculates changes in particulate matter from exhaust, physical activity from walking and biking, and injuries from traffic collisions, using state data like the California Household Travel Survey and SWITRS (the state traffic crash database) as inputs. The model estimates how many early deaths would be prevented, how many years of disability (from traffic injury or diabetes, for example) would be prevented, the diseases specifically related to particulate matter like heart disease and lung cancer, and road traffic injuries.

It produces some interesting results. Caltrans' goals, for example, would result in double the average amount of daily walking from a little over two minutes per person to about five minutes a day.

"We're not talking about marathons, folks," said Maizlish. "We're talking about five minutes per day." As he points out, this should be achievable; "but there's a lot of work between setting the goal and achieving it," he added.

He noted that the MPO scenarios are not at all ambitious, and would produce minimal results. Even the Caltrans mode shift goals would have small impacts.

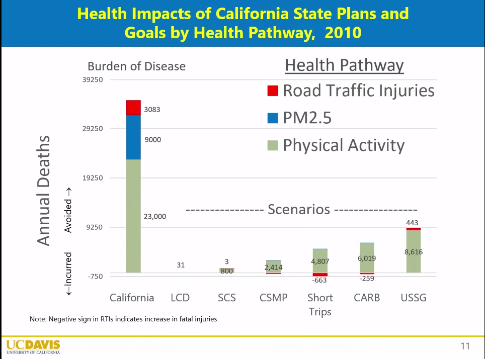

One key point is that, while air pollution tends to dominate the discussion -- and is important, especially for the environment and the climate -- strictly from a health perspective, getting people to be more active will have bigger impacts.

Bicycles can mitigate both emissions and the health burdens from lack of activity, so encouraging people to switch car trips over to biking trips would have the biggest health impact of all. This would also reduce greenhouse gas emissions, making it a powerful a climate strategy.

"Strategies that optimize bike travel are really good for health but they're also good for reducing car trips," said Maizlish. "We want a balanced portfolio, but we need to think about the specific role the bicycle has in carbon reduction."

His findings argue for stronger focus by all agencies - Caltrans, California Transportation Commission, Air Resources Board, and MPOs - on encouraging and facilitating safe bicycling in cities and everywhere feasible.

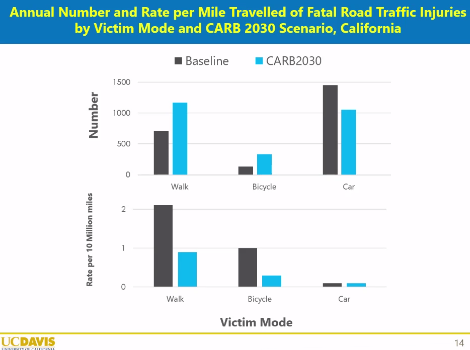

One of the model's findings, about traffic injuries, points out another potential issue that should be addressed. That is, as more people bike, the rate of injuries and crashes per mile biked would go down. However, the raw number of injuries would actually rise, because more people would be on bikes.

The phenomenon of safety in numbers -- wherein as more people bike, the number of bicycle traffic injuries go down -- explains the lower crash rate. But at least during the transition towards more widely adopted bicycling and walking, the overall number of bike and pedestrian crashes would rise.

This would need to be addressed by the same kinds of policies that can increase biking and walking -- e.g., better, safer infrastructure -- but could take more focused safety policies as well. Could we suggest, for a start, banning SUVs?

Ironically, the greatest crash safety benefit from reducing the overall number of miles driven by everyone would actually go to car occupants, whose risk of injury would drop as driving fell.

"One of the biggest threats to car occupants is other cars," said Maizlish. "When you reduce vehicle miles traveled, they benefit most."

Maizlish will present ITHIM findings tomorrow morning at the California Environmental Protection Agency in Sacramento. Information here.