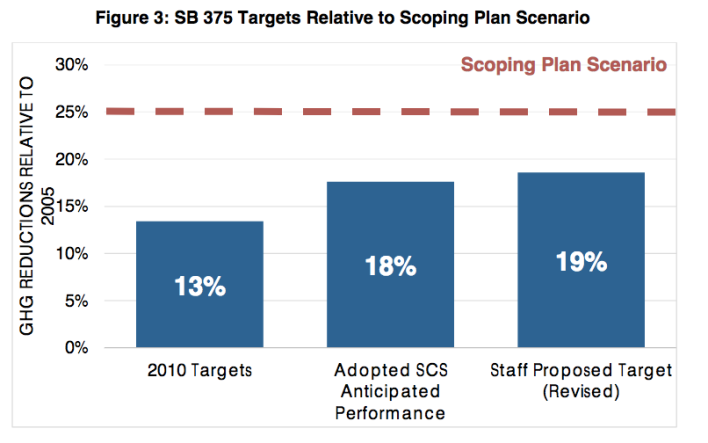

At a recent California Air Resources Board (ARB) meeting, the board adopted regional greenhouse gas reduction targets for 2020 and 2035, as required by S.B. 375. Each region was assigned a target--ranging from a three to fifteen percent reduction in per capita passenger vehicle greenhouse gas emissions relative to 2005 by 2020--with the amount increasing by 2035. Smaller regions generally have smaller targets; no region was assigned a target over nineteen percent for 2035.

The update voted on at the meeting was, according to staff, a “paradigm shift” in how the ARB approaches tracking and evaluating the effectiveness of Sustainable Community Strategies, which are part of regional transportation plans. Chair Mary Nichols said the update “brings greater focus to tracking and monitoring policies and investments at the regional level.”

This is key. Since it was passed in 2008, S.B. 375's effectiveness has been difficult to track, and its success has been marginal.

One of the first climate change laws passed in California, S.B. 375 was an attempt to get regional governments to better align land use and transportation planning so as to make it possible for Californians to cut down on the amount of driving they do. It requires, among other things, that Metropolitan Planning Organizations—MPOs, the regional planning agencies—come up with strategies that can help them achieve reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

The MPOs are responsible for planning regional transportation systems, and creating these Sustainable Communities Strategies was a way for them to influence how land-use planning happens, even though that remains subject to local control.

Transportation planning, even at the regional level, has traditionally been done in response to local “needs,” which in California has meant building freeways to get commuters to jobs that are farther and farther from their homes. MPOs have said there is little they can do to force local land-use planning to shift. They say the targets are too high, too hard to reach, and ultimately out of their control.

The one region which has probably found a way to gain some measure of influence on land-use planning is the Bay Area, where the Metropolitan Transportation Commission—the regional MPO—came up financial incentives for cities to build more densely near transit. But its plan, Plan Bay Area, took considerable effort and received a lot of pushback, and some cities have simply ignored it. The result is that even in the Bay Area, which has probably the best transit system in the state, transit still sucks in most places, safe bike facilities range from limited to nonexistent, and walking is neither invited nor accepted.

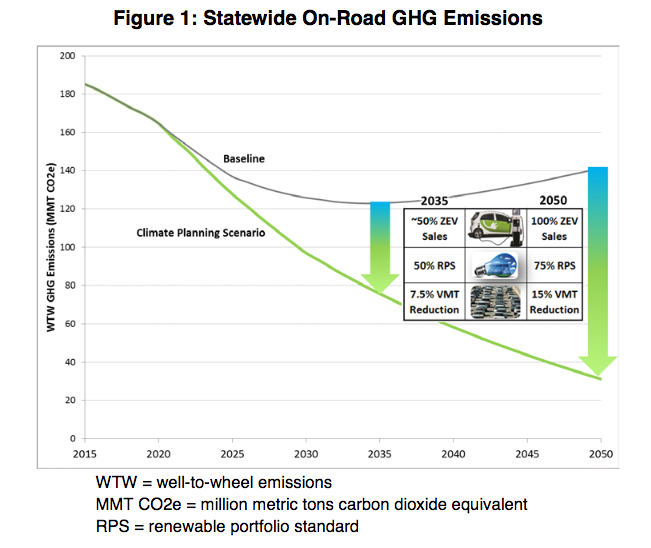

After a year-long discussion about how strict the new greenhouse gas emission reduction targets should be, ARB staff came up with a “compromise” that set targets higher than MPOs wanted but lower than advocates have asked for—leaving a substantial gap between what California says is needed and what it's asking the regions to do.

No one has offered suggestions as to how to close that gap.

At the recent ARB hearing, advocates continued to push for stricter targets, saying that if the regions don't aim high, transformative change will not happen and California will not meet its climate goals.

The San Diego region was singled out in particular as needing higher targets. This push came both from community advocates—like Ana Castro Reynoso, representing the San Diego-based Environmental Health Coalition—as well as ARB board members.

Reynoso pointed out that SANDAG, the region's MPO, has a “long history of misleading San Diego residents,” including supplying deceptive projections both of how much its transportation plan would reduce driving as well as how much revenue a local sales tax proposal would raise. ARB staff's proposed targets for San Diego, she said, are “more status quo” than game-changing. A higher target of 25 percent for the region, she said, would not just be “a paper target; it gives us a more ambitious target to push for.”

Last year's passage of SANDAG reform bill A.B. 805 “clearly demonstrates that we need strong enforcement from the Air Resources Board,” she said.

Residents of the communities around San Diego described the region's existing and planned transportation system as expensive, car-centric, emissions-producing, and climate-change-inducing. Several community members spoke of the difficulties of raising children near freeways and struggling with asthma. Margarita Morena, who lives in National City, said that “there is no transportation system [in the region] that takes into account my community and its needs.”

Other speakers pointed out that the City of San Diego has a Climate Action Plan with much stricter targets than SANDAG is willing to consider, and that members of SANDAG have openly stated that they don't believe their regional transportation plans must be consistent with local Climate Action Plans. They have also, they said, stated that reducing vehicle miles traveled is irrelevant to climate goals.

Just for the record: ARB staffmember Heather King stated at the meeting, “We will not hit our climate goals without [reducing vehicle miles traveled]. Reducing VMT solves problems that electric vehicles and clean fuels cannot.”

Others at the meeting pointed out that SANDAG dedicates less money to transit than any other MPOs in the state; that its transportation plans don't seriously consider prioritizing infill and transit over sprawl and freeways, and that, despite having an early action program to build a bike network, only four miles of bike lanes have been completed since 2013.

Of course these issues are not restricted to SANDAG. Other regions are still spending more money on highways than transit. SCAG is planning to build a new freeway, the Highway Desert Corridor, through empty desert in the Inland Empire; SACOG has identified a new rural highway, the East West Connector, as the most important transportation project in Sacramento area.

The urgency to settle these questions, in addition to the need to take action on climate change sooner than later, is that suddenly new money is available from the state gas tax. These “zombie” transportation projects that lie around in the planning stage for years until funding becomes available are starting to line up for money.

Bryn Lindblad from Climate Resolve told the board that the High Desert Corridor will even be receiving $2 billion of what SCAG is calling a $120 billion “transit investment.” The project will not only “unlock sprawl development,” as she said, it will “cut in half all the VMT reductions” that the remainder of the $120 billion “transit investment” would achieve.

“It's like we're trying to air out a smoky room by opening all the windows, but we're still fueling the fire inside the room,” she said.

Diane Takvorian, a member of the Air Resources Board, was also very concerned about SANDAG, and closely questioned that agency's representative. She said she was disappointed that the staff presentation “was not responsive to the San Diego community's call for increased targets.”

Although other regions also should probably have higher targets as well, she said, she particularly wanted to address San Diego's goals because of SANDAG's history, because SANDAG was the only MPO that did not call for higher targets in its 2015 SCS, and because of the changes on the way as a result of A.B. 805, which include new SANDAG responsibilities for transit and disadvantaged communities.

She proposed an amendment to adjust SANDAG's 2035 target upward from nineteen percent. “SANDAG's target probably should be 25 percent,” she said, “but I'm going to recommend that we change it to 21 percent.”

But ARB Chair Mary Nichols said that she was reluctant to vote on the issue because Ron Roberts, the San Diego region's representative on the Air Resources Board, was not at the meeting.

Besides, she said, “we've heard enough to know these numbers are largely symbolic.”

In the end, the amendment failed on a rare split vote, and the new targets were passed as recommended by staff.

It's true that the targets are symbolic. They symbolize how hard regions will need to work to reduce greenhouse gas emissions so we don't destroy the climate. They symbolize a number that communities can hold MPOs accountable for when regional efforts to reach the targets are too weak. They symbolize how hard it is to make wholesale shifts in the way we plan, fund, and build our transportation system, which California must do. Targets also symbolize the difficulty and importance of the changes each individual must start making in how they travel.

And when those symbolic numbers are set low, California's chances of shifting climate change are also low.