Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Researchers at UC Riverside presented new findings on pollution exposure for bicycle riders in a webinar this morning that raised more questions than it answered—although admittedly that is sometimes the function of research.

Bike riders are vulnerable road users, exposed to a variety of dangers, but the dangers imposed by pollution are not usually taken into account when planning bike routes.

Kanok Boriboonsomsin and Jill Luo are working on a method for measuring how much pollution bike riders breathe in while they are riding. Their research is in the early stages, and they warn that it's not yet ready to be applied to planning, but their early findings do give pause.

Riverside city engineer Nathan Mustafa said their results “are definitely an eye opener.”

Breathing in air pollution is “not what you necessarily think of first when planning bike routes; the number one safety concern is usually avoiding collisions,” he said. “But this is a concern we should be mindful of.”

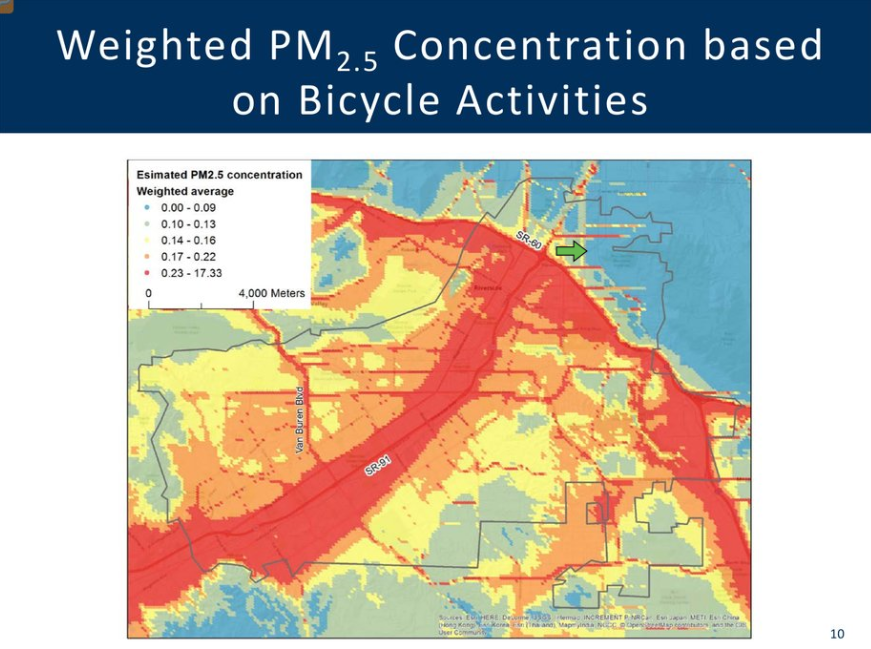

For example, the researchers found that traffic volume on a road doesn't necessarily predict the level of pollution a rider is exposed to. In the case of highways 60 and 91 in Riverside, where they conducted their research, the emissions from highway traffic means a high level of exposure to pollution on nearby roads that have relatively low-volume traffic. In fact, it is very close to the same exposure for a bike rider on the freeways themselves, and is related to wind direction as well as vehicle type and other factors.

For the moment, the research relies heavily on modeling local pollution, rather than actual measured data, because as of now there is very little local data available. Currently there are only forty air pollution monitoring stations throughout the entire SCAG region, which means air quality information is only available for large areas that don't correspond to specific routes—especially bike routes.

That might change with A.B. 617, which calls for better local monitoring of air pollution sources, although it remains to be seen what program last year's bill will create. The technology to measure local sources of all kinds of emissions exists, but it has yet to be deployed extensively.

The researchers focused on the city of Riverside, which has been moving toward facilitating active transportation. The city is about to embark on planning its first integrated Active Transportation Plan, and has in the works an ordinance to require complete streets components on road construction projects. It also recently designated an “Innovation District,” into which it hopes to attract new businesses and economic growth, while facilitating active transportation, transit, and other ways of reducing vehicle miles driven.

The research ranked local bike routes according to a variety of weighted qualities, such as connection to destinations, posted speed limit, estimated daily traffic volume, and grade. Then they added their estimated air pollution exposure rates, and saw the rankings of local streets change. For example, the case study showed that “University is not the most desirable route in terms of exposure to particulate matter [which the researchers used as a proxy for air pollution],” said Luo.

However, “that's the corridor we want to turn into a bike route with protected infrastructure, bike-share, and other uses,” said Mustafa. But he doesn't interpret this to mean that the bike route should be scrapped. “It's a call to action on that route to reduce vehicle miles traveled,” he said, “as opposed to just shifting bikes away.”

“When we plan out and approve land uses, we need to look at how we mitigate VMT along that corridor,” he said.

Later, Mustafa elaborated. “It's not just road diets. This is about action on the city's part.” The city wants to encourage economic growth in its Innovation District, but “in a sustainable manner,” he said. “We want to grow in a way that facilitates shorter trips and longer range transit; in a way that connects to the mobility hub that UC Riverside is constructing on their campus.”

That doesn't necessarily mean removing cars from the road, but encouraging other ways of getting around. “Even if you approve all the right land uses,” he said, “If we haven't done our job to make it comfortable, convenient, and safe to use our roads,” the city will not be able to reduce vehicle miles traveled, as called for by California state and regional guidelines on climate change. “The closer we come to achieving the state's objectives,” he said, “the closer we come to achieving our own safety and sustainability goals.”

Several webinar participants asked questions about how the pollution was measured, and how researchers determined the level of harm to various types of bike riders. Much work remains to be done on these issues.

But Bill Nesper, Executive Director of the League of American Bicyclists, pointed out something that bears repeating. That is, as currently understood, the health impact from people not riding bikes—from inactivity and car-bound living—is much bigger than the risk from all dangers to bicyclists, including breathing in pollution.

It's something we'd like to know more about in the future.