A report released today from the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) recommends that California's air monitoring agencies start using available technology to measure local air quality, especially where people live close to facilities that emit harmful pollutants.

The California Air Resources Board (CARB), with local air quality management districts, currently maintains forty sites that monitor local air quality statewide.

But those don't measure local emissions; the data they collect informs regionwide emission reduction plans. Instead, says the EDF report, it's time to begin using newer, cheaper, and readily available technology to measure emissions at their source—which is frequently right where people live.

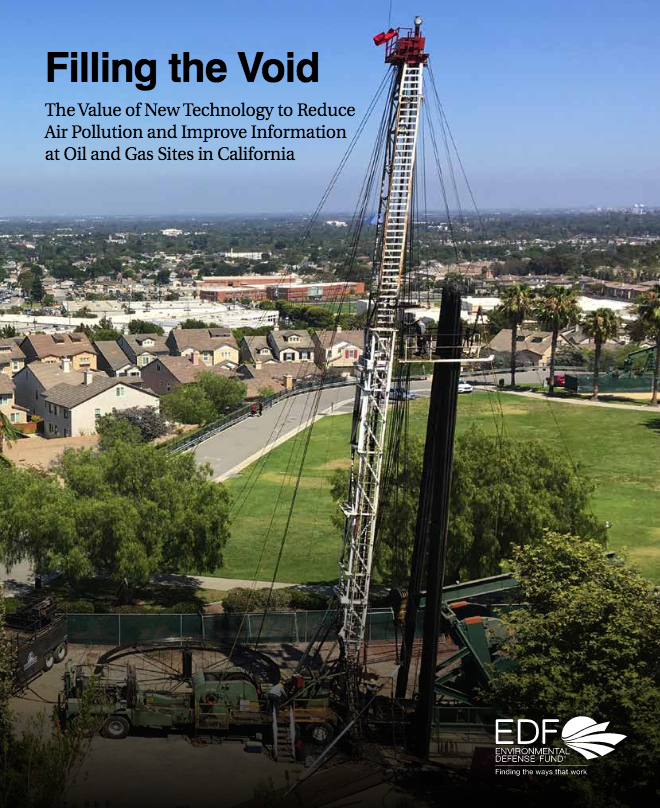

According to Timothy O'Connor, one of the report's authors, there are 54,000 active oil and gas wells in California—many in the Central Valley and many more in the L.A. basin—and not one of them currently monitors the emissions it produces. Hundreds of thousands of people live within a half mile of these facilities, many of them literally next door to them.

There are few regulations requiring the industry to monitor these sites. A bill passed earlier this year as part of the cap-and-trade extension, A.B. 617, calls for CARB to monitor local emissions, but many groups argued that the regulation isn't strong enough. It was seen as a sop to communities who were learning that cap-and-trade did nothing to reduce the emissions that directly affect their health, and as a way for the oil and gas industry to soften the rest of the cap-and-trade bill.

EDF, and the report's authors, are concerned that in implementing A.B. 617, CARB is going too slowly. “They're in the process of identifying what sites they want to monitor, and planning to deploy monitoring on a short-term basis,” said O'Connor. “But that's what California has been doing for years: deploying monitors for a short period. We're talking about installing monitors permanently.”

Permanent, high quality monitors can accurately measure not just methane but benzene and volatile organic compounds and other harmful pollutants 24-7, every day of the year. “These operations do not operate at a steady pace,” said O'Connor, “They may only emit for only a few months a year, or when there's a problem [like a leak]. But that's when people are exposed,” he said.

“We think these technologies can be deployed ubiquitously, and at a low enough cost to make it viable.”

“We do know that there are some limitations to rapid scale deployment,” said O'Connor. “There would be supply chain problems, and it would cost resources. But that doesn't mean we shouldn’t start.” He pointed out that the more the technology is tested and developed, the more costs will come down. “They can deliver data in the field right now. The way to do it is to identify those communities where people live close to active production facilities—in California, over 11,000 people live within ten feet of an active well. We should start there, then move on to other sites as we learn more through the deployment process.”

The report goes into some detail about the types of monitors available, and under what circumstances different types can best be deployed. But it also calls for regulatory changes that aren't in current law, including A.B. 617. For example, there is no requirement to include oil and gas sites in monitoring programs currently being developed

In the past the technology has been too expensive to put monitors everywhere, and it hasn't been seen as a viable path to data gathering. Because of that, regulations didn't focus on it, said O'Connor. But it's time for that to change.

EDF's report includes a list of recommendations for CARB and regional air quality management districts, including following L.A.'s lead by conducting an assessment of every producing facility in the state. In addition, they need to reevaluate current rules to update them in the light of better, cheaper monitoring technologies.

The state agency could require industries to install the monitors themselves. Or cities could follow the example of Los Angeles, which has begun imposing monitoring requirements through its land use control ordinance.

The data collected would need to be made available to the communities affected, and would inform plans to reduce and mitigate emissions. In addition, more and better monitoring data can help conduct health-risk assessments to improve regulatory decision-making, and provide solid data on appropriate buffer distances between facilities and communities.

The full report can be accessed here, and its recommendations are listed here.