The League of American Bicyclists regularly ranks states on how well they are doing to create safe and welcoming conditions for people who bike. Their last ranking, in 2015, put California at number eight.

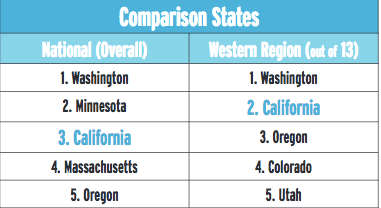

In the 2017 rankings, California leapfrogged ahead to third in the nation, behind Washington and Minnesota, of most bike-friendly states in the country.

California, says the League's report on the state's progress, “seems to be getting serious about biking and walking.”

The dramatic change from two years ago can be ascribed to a number of factors. One is Caltrans' release of the first-ever statewide bicycle and pedestrian plan this year. California is one of only five states that have updated their bike plan since 2015. Caltrans' press release says that the plan is part of the state's “multi-tiered” effort to ensure “the safety and comfort of people who bike.”

The plan, says Caltrans, “has allowed California to lay out a blueprint to fully integrate bicycling and walking into the fabric of the California transportation system. It is also Caltrans’ roadmap to achieve the department’s ambitious goals to double walking and triple bicycling trips by 2020, and reduce bicycle and pedestrian fatalities by ten percent each year.”

“It's very exciting that California adopted its first bike/ped plan,” said Ken McLeod, the League's policy director. “Some states with fewer resources just aren't going to invest in moving the state of infrastructure forward. When a state like California does these things, that can benefit other states as well.”

Another factor in California's leap in the rankings is the increase in funding for the Active Transportation Program. S.B. 1, the new gas tax, almost doubled the size of that program, from $130 million to $230 million annually. This is still a puny portion of the state's overall transportation budget, but nevertheless California is doing better than most states: the League ranks California sixth out of the fifty states in terms of dedicated bicycle funding.

California also increased funding for grants to integrate transit, bicycling, and walking into local transportation plans under the Sustainable Transportation Planning Grant program. And Caltrans also set itself goals to increase bicycling and pedestrian trips, which was a dramatic change from the department's previous perception of the “non-motorized transportation sector.” Much more needs to be done to get more traffic engineers on board with this new paradigm, but having the goal is a first step.

Another point in California's favor in the rankings, specified in the League's “report card,” is Caltrans' nascent plans to collect bicycle-related data, including crashes and counts. “Having accurate data on existing conditions is crucial for tracking progress and understanding differences between [Caltrans' twelve] divisions,” says the report.

California ranked at the top—first of all fifty states—for its policies and programs, in part due to the existence of Caltrans' Complete Streets policy, its endorsement of NACTO design principles, and the inclusion of active modes in transportation planning.

The state did less well when it comes to legislation and enforcement, however--23rd-- mostly because of a law on the books that requires bicyclists to use bike lanes. That is somewhat open to interpretation; sections of the vehicle code authorize bicyclists to “take the lane” under certain circumstances, and bicyclists are required to use the bike lane on roads that have one if they are traveling slower than traffic “except when making a left turn, passing, avoiding hazardous conditions, or approaching a place where a right turn is authorized.”

Several years ago, Caltrans Director Malcolm Dougherty asked the very pertinent question: “How is it that we are not the runaway number one bicycle-friendly state?”

It's true that there is no reason that California shouldn't be first in the bicycle-friendly state rankings. California has the highest number of bicycle commuters of any state and the sixth largest economy in the world—not just the nation—in addition to which the state claims status as vanguard in the fight against climate change.

But while California has a high bike commuter rate, it also has the fourth highest bicycle fatality rate per capita--and often in absolute numbers as well. The League report, in addition to ranking the states, makes suggestions for what states can do better. Bike safety is an area that California needs to work on—and also one in which the state could be a leader and innovator, says the report.

One of the purposes of the League rankings is not only to encourage states to consider the importance of focusing on improving biking conditions, but to provide feedback about how they can do better. Caltrans paid attention to previous suggestions, and took seriously past feedback, for example, on the importance of a statewide bike plan. The 2017 League report includes suggestions to:

- Continue and grow efforts to collect, report, and analyze statewide data on bike use and conditions

- Develop an inventory of bike facilities

- Focus on bike safety, using research and best practices both from within and outside of the state

- Repeal the state's mandatory bike lane law

To be considered in the League rankings, state DOTs have to fill out a long survey that asks for a lot of information. In the past, the questions on the survey asked for more than three hundred different bits of data, from bicycling conditions to laws relating to bikes to the existence of statewide advocacy groups.

“We got a lot of feedback from state DOTs that this is just too large,” said the League's McLeod. “At the same time we felt that we couldn't communicate the detailed information we were collecting” in a way that would do it justice. So they took a year off and reworked the survey, creating a new one that was “shorter, actionable, and impactful,” according to McLeod.

The new survey is only about a third as long as the previous one.

Even with the giant survey of 2015, all fifty states participated that year, sending in what data they had to answer the questions. In 2017, 46 states participated (although the League used what information it had to rank all fifty states).

That's a high level of interest, especially when, as in any ranking, some states are clearly not going to do very well.