As we close out bike month, it is worth noting that despite the growing acknowledgement that transportation must address equity, diversity, and the wider range of barriers that lower-income cyclists and pedestrians face when trying to access their streets, the frame of reference guiding programming around most "Bike to Work" days and weeks remains that of a rider of choice.

Yet, so many of the lower-income cyclists seen on South and Southeast L.A.'s streets have few choices about how they get around. And because their communities have been left behind when it comes to public investment, are heavily crisscrossed by freeways and heavy truck traffic, lack green space and street trees, and/or are home to toxic industries, their commutes are that much more fraught.

So much so that East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice (EYCEJ) - an environmental justice organization located on Commerce's wide and busy Atlantic Blvd. - found itself reframing the "Bike to Work" narrative last week.

Using the hashtag #BikeToResistance, EYCEJ staff and supporters documented the environmental health hazards they regularly come across along their routes and the glaring lack of infrastructure available to help them navigate safely past massive trucks and/or through wide streets populated with fast-moving cars.

The social media story-gathering effort was part of a larger push to highlight deficiencies in active transportation infrastructure in the Southeast cities. It culminated in last Thursday's release of Southeast Cities Measure M Local Return: Creating People Friendly Priorities, a report documenting the overwhelming need for investments in bike and pedestrian infrastructure in Southeast Los Angeles.

The report is much more than just a discussion of the region's active transportation needs, however. It's a call to arms - a plea to the Southeast cities to take a leadership role in investing local return dollars from Measure M in infrastructure that serves the area's most vulnerable road users.

As it stands at the moment, the Gateway Cities Council of Governments (COG) - serving 27 cities in the Southeast region - has balked on committing local return funds to active transportation.

The obstinance of the COG on this issue could have significant consequences for the Southeast cities, which tend to be lower-income and densely populated, largely Latino with sizable immigrant populations, and historically more underserved and generally more reliant on biking, walking, and transit than other cities under the Gateway umbrella. The COG's stance also stands in stark contrast to those of other county regions, which plan to dedicate between $30,000 and $361,000 to active transportation.

It’s also not the first time the COG has worked against the interest of its more vulnerable constituents. It has yet to allocate Subregional Equity Funds tied to Measure M. And when it came to backing an approach to the multi-billion dollar I-710 project - the effort to alleviate congestion along an eighteen-mile stretch of freeway while making goods movement along the interstate greener - the COG refused to support a comprehensive proposal that staked out active transportation and other benefits for the fifteen communities the corridor cuts through. [See more on Community Alternative 7, here.]

Given that the COG presents such a big hurdle, the EYCEJ report appeals directly to the Southeast cities, asking that they dedicate 100 percent of the local return dollars to improving and implementing active transportation infrastructure for the next ten years, coordinate with other cities within the Southeast to ensure connectivity, and work closely with the area's community-based advocates who know those communities well.

Commitment to funding active transportation for the next decade is particularly important, the report notes, because while the Southeast cities might have bike plans on the books or in the works, there currently are no bike lanes to speak of on their streets. South Gate has a two-plus-mile bike path that runs alongside Southern Avenue and weaves in and out of power towers, and considers a 0.8-mile stretch of what seems to double as a parking lane along the tail end of Southern (as it nears the river) to be a bike lane. And there is, of course, the river bike path serving all the communities that butt up against it. But active transportation has yet to be given its true due in the Southeast.

Part of the reason is lack of capacity. Efforts to create plans have thus far been funded by outside grants and generally drawn up by outside consultants. In order for the cities to be able to both plan and implement an active transportation infrastructure network, they need to find a way to make that aspect of the planning process more sustainable and make themselves more competitive for project funding. In the meanwhile, the local return dollars could help fill that gap.

Bryan Moller of Urban Health Strategies, the primary author of the report, and EYCEJ are hoping that the passage of S.B. 1 (a gas tax that will fund road repairs) will make it more palatable for Measure M local return funds to be dedicated to safer passage for the area's most vulnerable road users.

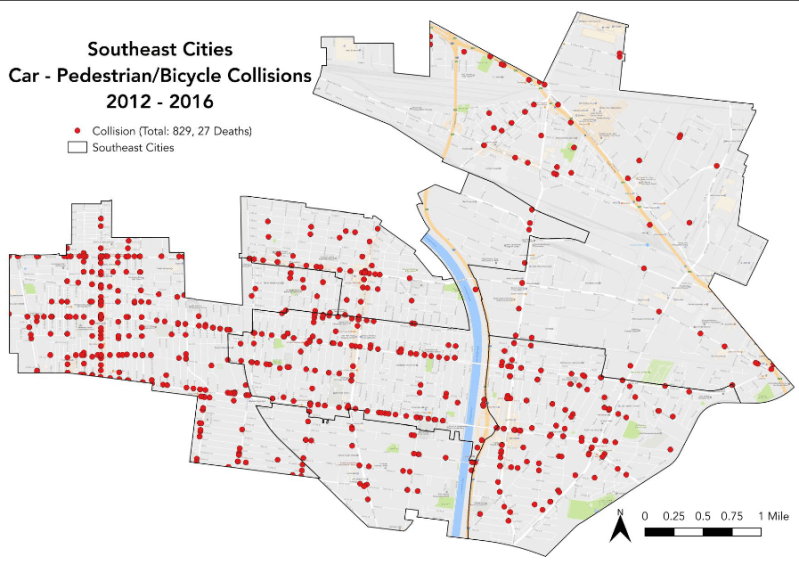

To make these asks more compelling, the report maps out the collisions that occurred in each of the Southeast cities between 2012 and 2016. And the results aren't pretty (see top photo).

Because the data is so recent, Moller says, it is important to remember that it is incomplete - and that more collisions may be included once the data is finalized. Even so, it presents a stark picture of just how unsafe some of the area's thoroughfares can be, with 27 people dying in nearly 850 bike/pedestrian crashes with vehicles over a four-year period.

Commerce, the smallest community population-wise, proved the most deadly.

Although there were a total of just 56 bike/pedestrian collisions with vehicles, eleven of them proved fatal. In other words, the odds that a pedestrian or cyclist will survive a crash in Commerce are about one in five.

As one might expect, the bulk of the collisions occurred along major thoroughfares packed with pass-through traffic.

With semi trucks comprising a significant proportion of the traffic rumbling down streets like Washington Boulevard, so little in the way of walk/bike infrastructure, and so few options by which one can move efficiently across the community, it's no wonder the odds of surviving are so bad.

Huntington Park, with a population about 4.5 times that of Commerce, saw far fewer deaths - just three - but nearly six times the number of collisions.

As with Commerce, collisions are concentrated along the wider and fast-moving thoroughfares that cut across and through the community.

But even with such clear evidence of where the danger lies and such a high number of crashes - 325 bike/ped collisions with vehicles - city officials seem to be reluctant to make interventions along those routes.

Just last fall, embattled councilmember and demoted vice-mayor Karina Macias moved to take the bike lane and other complete streets treatments planned for State Street off the table.

The reason given at the time, according to Moller, was the councilmember's complaints (over community members' objections and despite HP's own studies) that there hadn't been enough outreach and that a road diet would increase traffic. The result was that the years Huntington Park had spent trying to get an Active Transportation grant from Caltrans for that very project turned out to be for naught - the money would be released and the community's vulnerable road users would remain unprotected.

It's a turn of events that unfortunately isn't that surprising. In its 2014 bike plan, HP seems to shy away from the idea of bike lanes on the whole, describing its thoroughfares as having "relatively narrow street width" and declaring that "the potential for on-street bicycle lanes is limited due to the need to use streets for travel lanes and parking." Which means that even though Gage St. is consistently at the top of the list of dangerous streets for cyclists and pedestrians, HP is only contemplating putting sharrows there. A more recent complete streets study offers several potential alternatives for HP's major avenues. The fact that Macias was so quick to back down on improvements along a fast-moving four-lane street that cuts through a largely residential area and sees significantly less traffic than streets like Gage, however, raises questions about how seriously those alternatives will be considered.

This lack of infrastructure, Moller says, deters residents from trying to bike or walk in communities where biking and walking might otherwise make perfect sense. Like in Bell, for example, a city which, at its widest, is just about two miles from end to end. With most of its schools located toward the center of the city, the majority of Bell's students live within a mile or less of their school - easy walking/biking distance.

Yet because there are so few east-west streets that run all the way through and there's been no effort, as yet, to calm traffic, the streets that would do the best job in getting those folks where they need to go remain quite dangerous.

Residents of the Southeast communities are aware of just how dangerous the major thoroughfares are and how few options they have if they want to move across or through their communities. South Gate's 2012 study, for example, found that 82 percent of people surveyed saw not having safe streets to ride on to be a significant barrier to bicycling. There are quieter, bike-friendlier streets, to be sure - but they ultimately don't take folks where they need to go and they still require crossing and/or navigating the larger thoroughfares at some point.

For these reasons and more, say both Moller and mark! Lopez, Executive Director of EYCEJ and Goldman Environmental Prize winner, coordination between the Southeast cities is key.

Bike and pedestrian infrastructure along Atlantic Boulevard/Avenue - a major connector threading Commerce, Bell, Cudahy, and South Gate together and connecting them to Lynwood and East L.A. - won't be nearly as effective as it could be if it isn't continuous, says Moller. Where Cudahy has been active in seeking funds to make Atlantic safe for pedestrians and looking to make complete streets improvements to it, Atlantic doesn't appear to be on Bell's radar - there are no plans to add bike infrastructure there. In fact, Bell's bikeway plans seem to be aimed at moving people through the community from east to west. Except along the borders of the community (one of which is constituted by the already existing river path), there are no plans to help cyclists make connections within the community or move through it from north to south.

That EYCEJ should make these asks regarding active transportation and insist that the Southeast cities commit to them for the next ten years fits well with their original objections to Measure M. Fearing the Southeast would get more pollution rather than better transit and better active transportation options, and be more easily steamrolled in the weighing of options around the I-710 project, the organization had been vocal in their opposition to the ballot measure.

Lopez and EYCEJ remain concerned that funding formulas for local return will be adjusted and the Southeast cities will bear the brunt of those adjustments. But given that M did indeed pass, and passed with sizable support in the Southeast communities, Lopez believes that the long-underserved region is due its fair share. And given that the potential local return is dwarfed by the funds cities will be getting to fix potholes and do other road repairs, it's time the needs of those with the fewest transportation options available to them were finally addressed.

That sentiment is echoed by Tamika Butler, Executive Director of the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition, who argues that, with Measure M's passage and strong support from voters in the Southeast, "it's more critical than ever" to let the lower-income communities of color that originally opposed the measure know "that their concerns are not forgotten or overlooked." In the fight to right the past and current wrongs of environmental racism and segregation, she continues, "we stand with EYCEJ and Urban Health Strategies as they push elected leaders in Southeast Los Angeles to dedicate 100 percent of local return dollars to infrastructure for people who bike and walk... Behind EYCEJ's leadership, a real solution is being proposed to begin addressing the problems" faced by so many in these under-resourced communities.

Putting the active transportation asks in the larger context, EYCEJ's Lopez points to the number of ways that investments in infrastructure have done the Southeast communities harm. The siting of rail yards, freeways, and toxic and polluting facilities in and around communities of color and the parade of trucks encouraged to trek through them have left a terrible legacy. It is, he says, environmental racism enacted through the planning process.

Working to mitigate the impacts of mega-projects looming on the horizon (e.g. the I-710 and the Lower L.A. River Revitalization) while battling to ensure the clean-up of a decade-plus' worth of Exide's lead emissions is handled properly has only served to underscore how many different ways the health and well-being of lower-income communities of color continue to be undermined by a planning process that is neither inclusive of nor responsive to those communities.

In this context, attention to active transportation matters, Lopez says, because, "For many of us, walking and biking isn't just a choice, it is the only transportation option we have available. We ride in the face of the threat of violence: the historical lack of investment in our communities and the harm and death that comes as a result of...this lack of investment."

"The days of telling us we don't know what's best for us are gone," he continues. "The question is, will our cities work to resolve this or [will they continue to] perpetuate the violence?"

***

Find the report by Urban Health Strategies and EYCEJ, here. Learn more about some of the ongoing environmental issues the Southeast has faced by joining EYCEJ on their Toxic Bike Tour this July.

Many, many thanks to Bryan Moller for the hours he spent helping me navigate the Southeast cities' planning processes.