SCAG sent a last-minute letter attempting to delay progressive updates to California's outdated environmental standards.

In the letter [PDF], Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG)—the regional transportation planning organization for much of southern California—requested exemptions for highway expansion projects and freight corridors from proposed state rules that could show their true environmental impact in a way that old rules do not.

Regular Streetsblog readers know that the Governor's Office of Planning and Research (OPR) has been working on rules that will remove traffic congestion from consideration as an environmental impact under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

The impetus came from the slowly dawning realization that measuring—and mitigating—traffic Level of Service, which is what CEQA rules have done for twenty-plus years, was creating many unintended consequences that were detrimental to the environment. The way CEQA rules are carried out, if it looks like a project is going to cause traffic delay, planners must figure out a way to fix it. That in turn has led to street designs with wide lanes and overbuilt intersections that discourage people from choosing more environmentally friendly ways to travel than cars.

The rule-change process has taken a long time. Over the past two years, OPR staff traveled to all parts of the state to discuss Level of Service issues to gather ideas and feedback from experienced planners and engineers. They settled on substituting Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) for Level of Service (LOS). Streetsblog coverage of the reasons for that choice can be found here; in brief, measuring how much travel a project induces rather than how much it slows traffic gives a better idea of its true environmental impact.

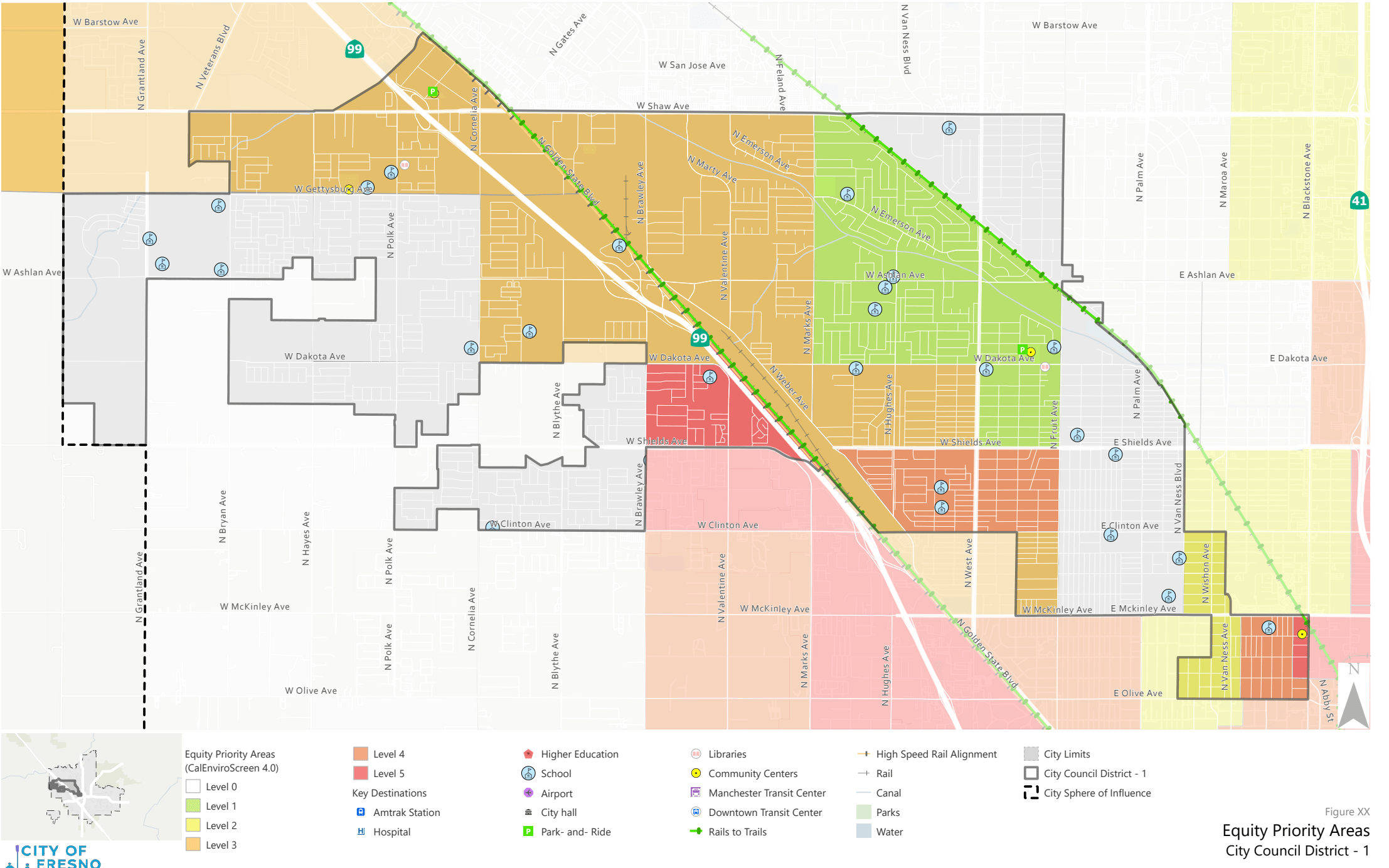

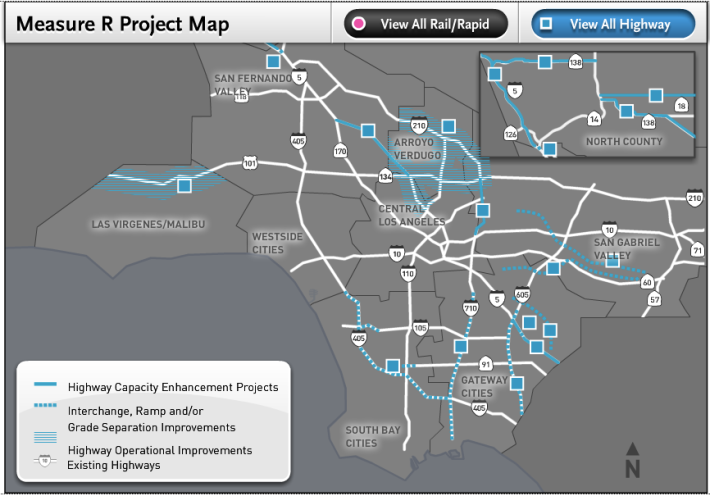

The deadline for comments was February 29, and SCAG's letter came in just under the wire. In it, SCAG requests that OPR limit the new VMT measure to projects that are close to transit, and also to “grandfather in” highway expansion and freight corridor projects that have already been approved in planning documents.

“In other words,” said Amanda Eakin of the Natural Resources Defense Council, “SCAG is saying not to apply the VMT metric to the projects that are most likely to cause more VMT.”

To the NRDC, SCAG's request makes no sense. “As a state,” she said, “we've acknowledged all the problems with LOS, and have agreed to move to a new measure that can promote greenhouse gas reductions and other environmental goals. It makes no sense to apply the new metric to only certain projects.”

“If we know that capacity expansion projects are going to increase VMT, then we have to be examining that now,” she added.

Ping Chang of SCAG told Streetsblog that SCAG's primary intent with the letter was to request that OPR focus first on transit priority areas and allow a longer opt-in period for other areas. “It does take some time for cities to revise their internal systems,” he said.

But a longer opt-in period isn't the same as grandfathering in certain projects, and SCAG's stated reason for skipping VMT analysis is simply that they had already been approved, sometimes by voters (such as the Measure R projects in L.A. and Measure M projects in Orange County).

SCAG's objections seem to be that the guidelines still need some work. “For areas within Transit Priority Areas,” said Chang, “they are ready. In other areas, we still have a lot of questions as to how they will be implemented.”

That's fair, although it's not clear why the distinction. Is it that for projects that are likely to induce more travel, the consequences of finding that out are unknown—and maybe scary?

VMT analysis is already carried out for those projects, according to Chang, but it is not used to determine mitigations under CEQA. “This changes the standard,” he said.

Chang said that among SCAG's objections is that, if VMT analysis has to be done on for individual projects, it could show a falsely high level of new travel.

“Transportation use is a network,” he said. “No road can function in isolation. Changes are a result of a network as a whole, and individual project analysis needs to take into account this network analysis.”

But he also denied that induced demand is real, saying that any increased travel as a result of SCAG's highway expansion projects will only come from “natural increase.”

“We are not attracting a lot of people to our region because of our transportation investments,” he said. “We are not attracting a lot of jobs from other regions. This is about catching up. The reality is that our transportation investments are primarily about catching up to the demand.”

For others, however, the concept of induced demand is well established and not so much subject to question as likely to cause some consternation, especially in connection with highway expansion projects. And as NRDC's Eakin pointed out, if projects are going to induce travel, no matter where it comes from, we should know that now.

Greenhouse gas emissions aren't going to decrease magically while Californians increase driving, and building highway expansions to meet existing demand doesn't leave any room for thinking about better, more enviromentally friendly alternatives.

SCAG's letter raises good questions about the details of how to implement the new guidelines, and there probably is more work to be done to figure out how to properly measure the VMT effects of individual projects within a larger regional context.

It's a point well taken, since one lesson learned from the outdated LOS measure was that regional vs. local impacts could be quite different. An LOS measure, for example, shows less congestion impact for projects in areas that have low traffic volumes, but similar projects in areas with higher existing traffic numbers show a much bigger increase in traffic delay. Thus LOS has helped make small-scale infill more difficult to build than large developments in outlying areas.

But tweaks to the guidelines don't mean the rule-making process has to be slowed even further. And grandfathering in highway expansion projects just because they have already been approved doesn't add up. Those projects are the ones whose effects on traveling—whether measured by individual project or in the context of other development—need to be studied.

OPR is currently proposing a pretty generous two-year opt-in period, during which cities, counties, and regions can “adjust their internal systems” to meet the new rules. San Francisco has already formally adopted VMT and dispensed with LOS—and while not all regions are in the same position as San Francisco, they have already had two years to think about what's coming, and they have two more to adapt to the new rules. Meanwhile, climate change is not getting any less urgent, and the projects being built now will have an impact on all travel—be it by car, bike, foot, or transit—for years to come.

If SCAG and others really need more than two years to adjust, they should be more specific about why, rather than just ask for a blanket dispensation for certain projects.

For updates on California policy that affects transportation, follow @StreetsblogCal on Twitter, or subscribe to our daily email in the box at the top right of this page.