The success of a parklet in Redding, California, may one day lead to official Caltrans design guidance for similar projects on state highways.

At least, that is the hope of local advocates at Shasta Living Streets, who built the parklet as a pilot, with Caltrans permission, on the state-controlled highway through downtown Redding.

As far as Streetsblog has been able to discover, Redding's is the only parklet Caltrans has permitted on a state-controlled road. There may have been one in Fresno for a few hours during Park(ing) Day this year, but that's been difficult to confirm—if anyone has details about that parklet, please tell us in the comments.

The only official Caltrans-sanctioned parklet was on California Street in Redding over two time periods—for three days around Park(ing) Day in September, and again for ten days in the same spot last week.

But, organizers say that they have been told that no more such pilots will be approved on state highways, at least in District 2, until Caltrans develops some kind of standard policy for parklets.

By all accounts Redding's parklet was a huge success. It brought lots of visitors on the days it was in place, and even after it was removed people were still looking for it, according to Shasta Living Streets director Anne Thomas, who spearheaded the effort to create the parklet.

“Walkable cities and public space amenities like parklets are part of the Shasta Living Streets vision for business districts in our region,” said Thomas. “We looked for ways to share that vision—to help people understand what these things are and why they are valuable, and to facilitate and speed up the process for getting them, including removing barriers.”

Brian Crane, the city's Director of Public Works, says that as a result of the pilot, the city of Redding is putting together its own local standards and policies for long-term permanent parklets. These guidelines would apply to streets that are not controlled by Caltrans.

The potential for Caltrans to create state standards was an unexpected bonus. “I've asked [headquarters to] consider some form of guidance so we can be consistent,” said Dave Moore, the interim director for the local Caltrans district. “But I don't know what the end product will be.” He and his staff have not completed their evaluation of the parklet, which would help inform any guidance Caltrans ultimately creates.

Kevin Herritt, chief of Caltrans' Office of Standards and Procedures, says that Caltrans is already working on it. "We're looking at what's already out there, and what's already been done," he said. Oakland and San Francisco, for example, have developed local standards, and there's no point in reinventing the wheel. "A lot of it is community-related," said Herritt. "Whatever the community desires, we're going to have to coordinate and blend in with. We're going to be flexible and make sure the guidance works for them."

“Providing livable space in and around the state highways is part of the Caltrans mission, vision, and goals,” said Moore, “and we're probably going to see more requests like this across the state. We'll need to take a good look at them and see if we can make them consistent with other needs on highways.”

“Typically, though, state highways are the least appropriate places for parklets,” he added, although many of us can think of exceptions where state highways function as local streets.

In Redding, as in many California cities, the state highway cuts right through the downtown business district. State Route 273 splits into two parallel one-way roads in Redding's central district, along Pine and California streets. Last year, California Street was due for a repaving, so Shasta Living Streets worked with Caltrans to support a redesign of the street to make it safer for pedestrians in the area. It ended up on a “road diet,” which narrowed it from three vehicle lanes to two, with extra space given over to a bike lane.

A successful open streets event put on by Shasta Living Streets in May showed local businesses the possibilities inherent in slowing down traffic and making the street more inviting for people who are not in cars. “Businesses liked this event,” said Thomas, “and that's when the idea of a pop-up parklet was first discussed with business and downtown property owners, who liked the idea.”

Shasta Living Streets also worked with California Walks to host a local workshop to discuss how to make downtown more walkable. “Most of the people in the workshop asked for amenities like parklets for downtown,” said Thomas.

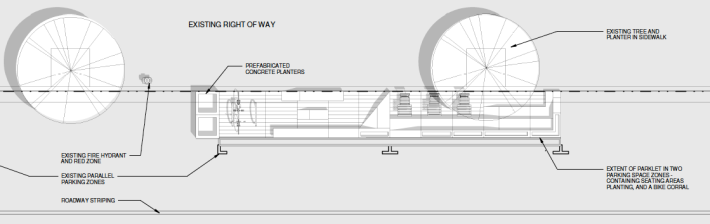

The road diet on California street left plenty of room—a good five to six feet—in the right of way between parked cars and the outside travel lane. That was where organizers wanted to put the parklet, and the extra space may have helped ease Caltrans concerns, according to Crane.

“Without the road diet it would probably have been a little more difficult to get Caltrans to agree,” he said.

Thomas also wanted to make sure that local businesses would see the benefit of a parklet, so Shasta Living Streets volunteers not only built the parklet, using $5,000 of donated wood, they also fixed up an adjacent empty storefront. “We called it 'Popup Parklet and Market Hall,'” said Thomas, creating what she called “a kind of mini-Ferry Building, with an art exhibit inside. There wasn't a whole lot to buy, but in the morning, there was coffee and pastries, and in the evening we had wine and beer.”

“During the first pilot, in three days we got 4,000 people coming to see the parklet. Everybody looooooved it. People were amazed.”

She said that during the three days that first pilot was up, the parklet also got visits from the mayor, from city councilmembers, and from the local Caltrans district.

“It drew so many people, and we had TV, newspaper, and online coverage,” she said. “There were easily many more people who knew about it than the number who visited. For weeks afterward, local businesses said people came to them to ask where it was; they wanted to check it out.”

The excitement created a wave of support to try it again, and nearby businesses pushed for a longer pilot.

Local Caltrans staff were interested but wary, anticipating that getting permission from engineers at headquarters for a longer time period would be difficult. Without promising anything, they encouraged Shasta Living Streets and the city to submit a request for a pilot that would last for two weekends plus the week in between.

“If you submit something, we will respond,” is how Thomas said they phrased it. It was also an opportunity to do a longer test to see whether some local objections that had been raised—that someone would run into it in a car, or that homeless people would sleep in it—were actually a problem or not.

“We had to put a fence on one edge,” said Thomas, “and surround it with traffic cones. We minimized the size as much as possible.” But the response from Caltrans, in the end, was “yes.”

“This is how change happens,” said Thomas.

The buildings along that section of California street are being rehabbed, repainted, and newly rented since the street diet, said Thomas. There is even renewed interest in the space that was used for the Market Hall. “Our project is adding energy to that,” she said.