For more than fifty years, U.S. transportation planners and engineers have focused their energies and our investments on building a transportation system that moves private cars as quickly and efficiently as possible. This worked to make it easy for many people to get around - up to a point. Increasingly, however, a pileup of factors is making it harder and harder to rationalize the practices, funding mechanisms, and even philosophies that made the 20th century the embodiment of personal freedom via driving a car.

Those practices were adopted as solutions to real problems, writes Dr. Susan Handy, Distinguished Professor of Environmental Science and Policy and Director of the National Center for Sustainable Transportation at the University of California at Davis, in Shifting Gears: Towards a New Way of Thinking About Transportation, from MIT Press. But they stem from a set of core values that remain largely unquestioned. Handy quotes Charles Marohn, who says these values "are so deep, so core to the profession that practitioners do not consider them values... They are merely self-evident truths."

Handy's book takes a deep look at those core notions, and an equally critical look at some of the new ideas that are trying to shift transportation planning towards building a safer, more equitable, more environmentally sustainable system.

Freedom is one of those core ideas. It has become equated with cars: the freedom to drive wherever, the freedom of the open road. On the face of it, that's not a terrible notion, but fifty years of trying to accommodate that freedom has resulted in more cars, terrible congestion, pollution, and a lack of safety and freedom for people who aren't in cars. Freedom from cars was not what traffic engineers were thinking about.

More core notions: speed is of the essence. Congestion needs to be solved. Mobility requires being able to go quickly and smoothly from any point to any point.

Accepting these ideas as principles led to adopting strategies that seem to work, at least at first: increase capacity (add more room for cars); create traffic controls and enforce rules; separate different road users so as not to interfere with the fastest movers.

Old Ways Are Not Working

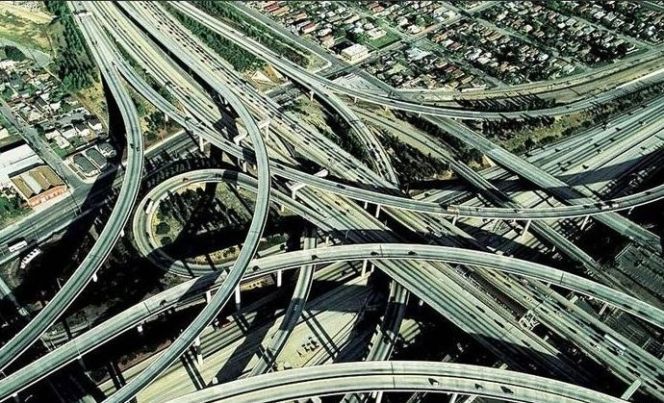

Handy's academic work, and the work of others, has shown that congestion can't be solved - at least not by any of the strategies used over the last fifty years, including adding more room for cars. The well-understood notion of induced demand has been discussed - and dismissed - for years, even as it is becoming clear even to casual observers. People who endured years of construction on the 405 in west L.A., for example, expected to a new lane to help ease the hellish slowdowns there. But it just filled up with more traffic almost immediately.

Other engineering "solutions" have brought new, bigger problems, largely ignored by transportation planners as not being their responsibility. Homes and communities have been wiped out by road expansions, or left to deal with increasingly bad air quality from the freeways that cut through them. Pedestrian death and injury rates are staggering and tragic. Expanded pavement requires more maintenance, but takes funding away from road repair, which is in really bad shape. Water quality is being destroyed by microplastics, oil, and brake particles from street runoff. Wasteful and harmful fossil fuel use is encouraged, when it should be reduced. Huge amounts of resources are poured into materials to pave roads and make cars, twelve million of which are scrapped ever year. Wide expanse of pavement cause excessive heat. Roadkill is everywhere.

These harms are not equally distributed, either, with lower-income communities of color bearing the brunt of them, from bulldozed communities to bad air to high injury rates.

The benefits of this transportation system are also not equally distributed. The quicker car travel that is the focus of these "solutions" aren't much help to the thirty percent of the population that cannot drive, especially when new highway investments take the lion's share of transportation funding, leaving public transportation, bikeways, sidewalks, and safety improvements to fight for scraps.

The limits of traditional thinking about transportation planning is leading to a necessary paradigm shift, says Handy, but it is slow. "The ideas that explain why we have the car-oriented transportation system we have also explain why change is so difficult," she writes. The shift can be seen more clearly on a local level, where cities are responsible for local streets as well as land use planning. But "cities working to improve conditions for transit, walking, and bicycling are working against decades-old policies favoring cars that the cities themselves have adopted."

These include everything from parking policies to road engineering to land use policies that make it easier, and cheaper, to build on undeveloped land at a city's edge than on smaller infill parcels, where public transportation could more efficiently serve more people.

Looking Deeper at Why

"I wrote the book for anybody interested in what's going on in transportation, who wonders why we've done things the way we've done them, and why things aren't better than they are," she said in a recent interview.

"There are a lot of books out there that say, 'Here's what we should be doing.' But I wanted to go a level deeper and take a look at the way of thinking that explains what we've been doing, because I feel very strongly that do to things differently, we can't just change policies. We have to change how we think about things. And it will be hard to get much change until we examine some of the deeply embedded beliefs we have about transportation and what transportation professionals should be doing."

But to make any change, first one has to identify what change is needed. That's what has been missing for transportation planners, who are stuck in a paradigm they were trained for but which is not holding up as time passes. They "are doing their jobs the way they've been trained, the way various guidebooks say they should be doing their jobs," said Handy.

"We may be adopting new ideas, but we haven't yet let go of the old ideas," said Handy. "It's been a slow process of these alternative ideas finding their way into professional practices, and policies being implemented." This has created "kind of a muddle with our transportation thinking." What seems to be happening lately is a "throw everything at it approach," where induced demand is kinda sort accounted for, and some of it is "mitigated" with various strategies - but a lot of road building is still happening.

"It's not clear that makes sense," said Handy. She gives a local example in Sonoma County, where "we're spending $700-and-some-million on building a commuter rail system (Sonoma Marin Area Rail Transit, aka SMART) and at the same time we're spending $700-and-some million to widen the freeway that's parallel to the rail."

"If we were serious about increasing transportation options, we'd be putting all that investment into transit," she said.

"Since writing the book, I've come to see a big part of the problem is the obsession with congestion," said Handy. "Even when in comes to investments in transit - there's so much focus on the need to reduce congestion. Yes, it's a problem. It's awful to be in it, and it imposes real costs. No one wants to be stuck in it. But we have a lot of other problems we need to be addressing."

Paradigm Shift

When Handy looks at the ways things are changing, she finds some hope. For example, there is a growing attention to - and understanding of - the principle of induced demand. The elimination of parking minimums has been opening up an understanding that requiring and providing free parking everywhere may not be the best use of space. There is also a growing rejection of the 85th percentile rule for setting speed limits, which just led to faster and faster speed limits in the name of... who knows what.

But congestion remains at the top of concerns, frequently - no, always - used to explain the need for investments in road expansions, because to traffic planners, increasing capacity remains the solution. While Caltrans director Tony Tavares has stated that it the state transportation department has done a complete pivot on highway expansion, Handy writes that the pivot is "more aspiration than reality."

The risk is that if we continue planning transportation the way it's always been done, we not only don't make anything better but we waste investments.

"I think it's wrong to think about solving congestion by reducing congestion," Handy said in the interview. "Another way to think about it is to make congestion less relevant. One way would be to increase local accessibility and give more priority to walking, bicycling, and transit. If you don't have to get on a freeway to get the goods and services you need, you don't worry so much about congestion."

Handy ends the book with a discussion of the slow pace of change. New guidance has allowed traffic engineers more flexibility, but they have been slow to take advantage it. Flexibility can make decision-making more complicated - which can, ironically, lead to a reliance on "engineering expertise" to make the final call, putting final decision-making power into the hands of engineers - who are still trained in the old ways of thinking. That leaves other experts - community members who know what their communities need, for example - out of the loop. "Every decision about transportation implicitly or explicitly reflects a definition of the problem to be solved and an ordering of competing goals - and these are matters of values rather than technical expertise," she writes.

That's why it is important to dig deep beneath standard practices and strategies to understand the values that underlie them, and to ask: is this the transportation future we want? Or do we want something else?