In a major settlement with the families of gun violence victims, an American weapons manufacturer is being held accountable for its dangerous advertising campaigns — but legal experts say it's unlikely that the victims of traffic violence can successfully sue American automakers on similar grounds despite similar violent ads.

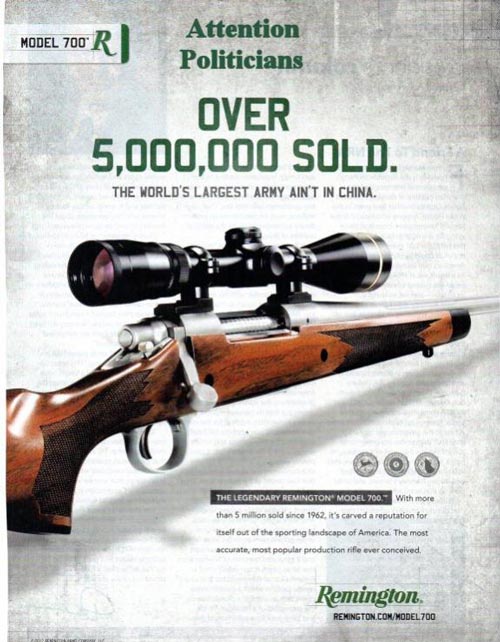

On Feb. 15, the families of nine of the victims of the Sandy Hook shooting announced that they had reached a $73-million settlement in a lawsuit against Remington firearms, which manufactured the AR-15 rifle that shooter Adam Lanza used to kill 20 children and six adults at a Connecticut elementary school in 2012.

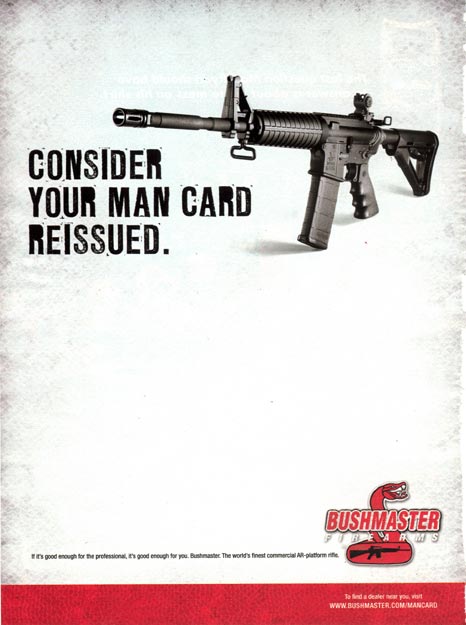

The legal grounds for the suit focused largely on Remington's marketing and advertising campaigns, rather than on the inherent danger of the company's guns themselves. Weapons manufacturers enjoy broad immunity from litigation under federal law, but a carveout in the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act in 2005 allowed the Sandy Hook families to successfully argue that the company had “marketed, advertised and promoted the Bushmaster XM15-E2S for civilians to use to carry out offensive, military style combat missions against their perceived enemies" — essentially encouraging violent men like Lanza to commit massacres with their product.

Remington has long been notorious for marketing guns like the AR-15 — which was originally developed for military use — as civilian weapons capable of transforming average men into macho super-soldiers, without which their "man card" might be revoked.

Street safety advocates quickly pointed out that U.S. automakers often employ similar messaging, including whole ads devoted to staged focus groups questioning the relative manhood of sedan and pick-up truck drivers, voiceover copy that openly compares Dodge drivers to "predators," and endless depictions of drivers speeding, swerving, and otherwise breaking the law and endangering others, with only a microscopic disclaimer to clarify that only a "professional driver" on a "closed course" should attempt such maneuvers. Studies have shown that drivers who watch depictions of reckless roadway behaviors are more likely to think that driving that way themselves is okay.

Whether Connecticut's consumer protection laws might apply to reckless automakers, though, isn't totally clear — and legal experts say it's unlikely that the families of loved ones lost to traffic violence could get justice under similar statutes in other states, either.

For one, fair trade laws are typically aimed at preventing companies from under-selling the dangers of their product in such a way that it poses a "public nuisance" — or in some cases, a threat — to their consumers and the public at large. That's part of why companies that make legal products that everyone knows kill tens of thousands of people a year, like guns and cars, are rarely the target of successful lawsuits, unless their manufacturers lie about the scope of the harm that they cause.

"The public nuisance approach, which we have seen in the opioid litigation and now in the climate change cases, seems have more to do with misrepresentation by the manufacturer, rather than commercials that depict reckless driving," a representative for the American Bar Association told Streetsblog. "With opioids, the manufacturers insisted they were safe. With climate change, the oil companies denied the effects of their products caused. While the latter remains to be seen on whether liability will attach, I have a hard time seeing its application to autos."

Second, the fact that liability did "attach" in the Connecticut case was only the judgment of a single court — and plaintiffs in similar cases might not be so lucky, even if they also lost loved ones to gun violence in the very same state.

In a recent article for the Conversation, law professor Timothy Lytton of Georgia State University explained that when it held Remington accountable under the state's Unfair Trade Practices Act, the Connecticut high court had actually broken with the opinion of judges in other communities, who ruled in previous cases that state consumer protection laws don't apply to gun-makers unless they're written specifically about gun-makers.

"The court said that a relevant statute only had to be 'capable of being applied' to gun sales, not that the law needed to be specifically about firearms, as other courts had held," Lytton wrote. "It is this interpretation that could potentially prompt a flood of lawsuits across the country."

But because the Sandy Hook case was so unusual, Lytton himself isn't convinced that "potential" flood will actually be unleashed — and that means the makers of other dangerous products, like cars, probably don't have much to worry about.

Critically, Lytton points out, the Sandy Hook lawsuit ended in a settlement, which means it does not set a legal precedent even in the jurisdiction where the settlement was achieved — and it will never have an opportunity to be challenged up to the Supreme Court, where it could someday set a national one. Moreover, he argues that "Remington’s reasons for agreeing to settle may have more to do with the company’s struggle to reemerge from bankruptcy than a newfound willingness among gun-makers to settle claims" — which means people who sue financially healthy gunmakers would face far more significant challenges.

Take a tip from Sandy Hook parents who just got a big settlement from Remington. We need to go after these companies for their marketing. Get the documents. It's all intentional. Listen to Alex Witt on MSNBC last night, and substitute Dodge for Remington, you have the case.

— @bikeloveny@post. (@bikeloveny) February 16, 2022

Without a strong legal precedent in place, a litigant who sues a thriving U.S. automaker for the harm caused by its habitually dangerous ads would face an even steeper uphill battle. Experts we spoke to said it doesn't seem like a U.S. court has ever applied a general consumer protection law related to dangerous advertisements to car manufacturers, and there don't seem to be laws on the books specifically aimed at protecting the public from the negative consequences of ads that depict reckless driving, either.

Of course, that doesn't mean automakers shouldn't face accountability for bad ads — or that lawmakers couldn't be doing more to crack down on commercials that treat a vehicle's deadliness as a selling point rather than a defect, at least when it comes to people outside the car. Regulators in the United Kingdom and France have done just that, and automakers themselves in Australia have adopted their own strong voluntary standards.

Until American leaders follow suit, U.S. traffic violence survivors will probably have to seek justice in other ways — like lobbying for safer vehicle designs, street designs, and policies that might prevent other families from enduring tragedies like theirs. If they win, automakers may still be able to show their drivers doing donuts and speeding on TV — but at least the real-world motorists who do the same thing will be less likely to kill.