The average motorist will pay a whopping $650,000 on the low end to own a car over his or her lifetime, and society will pick up over 40 percent of the tab, a new study finds — and because those numbers are based on German travel behaviors, costs are likely even higher in America.

In a new study in Ecological Economics, an international team of researchers comprehensively modeled the costs of automobile ownership over 50 years, accounting not just for the price the driver pays to keep the car running, but the cost that society pays as a direct result of that driver's choice of mode.

Both categories, unsurprisingly, were pretty expensive. With fuel, insurance, repair, the price of the vehicle itself, its depreciation over time, and even occasional costs like car washes, licensing fees, and parking fees, the average German driver can expect to pay about $404,375 for a lifetime of driving — provided she sticks to small models like the Opel Corsa (an economy-class electric hatchback that's around the same price and length of a Mini Cooper SE) and drives it less than 9,320 miles per year, which is roughly the German average.

That same drivers' neighbors, though, will collectively have to pay about $245,600 in public subsidies over the course of that driver's life, between the costs of building and maintaining autocentric infrastructure, public health costs for which the driver is not directly responsible — think uncompensated crash damages, air pollution, and noise pollution — the rising costs of climate change, and, of course, free parking. And again: these estimates are based on an electric car.

The study did not model the comparative costs of active and shared transportation, but earlier research has showed that biking generates a net benefit to society of 32 percents per mile, while costing the rider herself next to nothing; transit users, meanwhile, generally enjoy a higher per-mile social subsidy than drivers, depending on how you calculate those subsidies, but actually end up costing society less over time, because U.S. motorists travel so much further every year.

Of course, the financial toll of vehicle ownership goes up the more expensive, heavy, dangerous, and dirty a car is.

To get a sense of just how much, the researchers also modeled the lifetime costs of a Mercedes GLC SUV, which topped out at over $1.09 million over the course of the motorist's lifetime, 29 percent of which was borne by society on the whole. The researchers say their methodology could be applied to virtually any car on the market, if it's adjusted for national trends.

That gives some idea of the lifetime costs of a typical (read: gigantic) American vehicle, but there are still critical — and depressing — differences between the countries' travel behavior that would need to be accounted for.

The average American, for instance, drives 13,476 miles per year, or about 44 percent more than her German counterpart — and it's probably not because she's circling the block looking for a free parking space. Transportation research firm INRIX estimates that the average German motorist spends 41 hours per year searching for a spot; in America, that estimates is just 17 hours.

Regardless of the precise dollar figure, though one thing is clear: countless Americans would benefit from a transportation network that doesn't require them to take on the onerous costs of private vehicle ownership in order to participate in society, or to subsidize the choices of their neighbors who do.

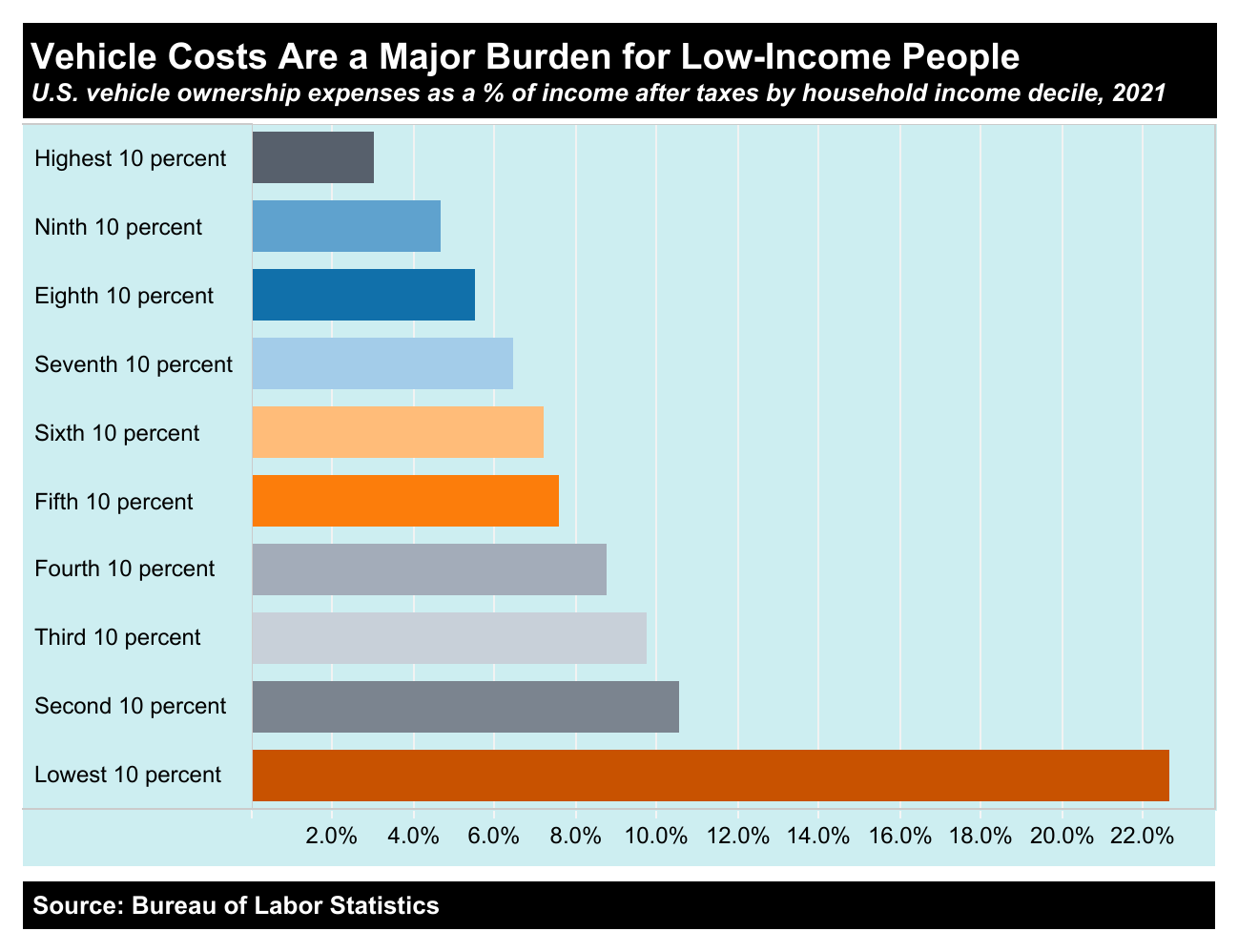

And particularly for the poorest Americans, those costs can mean the difference between thriving and barely surviving.

In a recent study from Inequality.org that was re-published by Streetsblog, researchers found that "for the poorest 10 percent of U.S. households, the share of after-tax income going to vehicle costs (22.6 percent) is 7.5 times as large as the share spent on vehicle costs by the richest 10 percent" — and that wasn't accounting for all the money that diverted from those households' taxes to pay for the societal costs of driving.

"U.S. transportation policies privileging roadways and personal vehicles over all other modes of travel have not served the economic and transportation needs of all," wrote study author Basav Sen. "They are a public subsidy for disproportionately white, wealthier households, at the expense of the rest of the population."

Correcting for those inequities would be a revolution in transportation — but experts say it might be easier to accomplish than you'd think.

"In our research, we’re not saying you should start taking away cars from people," the study's lead author Stefan Gössling told Forbes. "We’re just saying it’s probably more prudent, economically, to invest in those infrastructures that are less costly — such as for active mobility — and where people will make a switch voluntarily.”