Depending on who you ask, the race to create an autonomous vehicle is either a heroic quest to end traffic violence, or a dangerous gamble that's draining resources from proven traffic safety solutions in favor of a fool-hardy technological race that could end with the automobile claiming the top spot in our transportation hierarchy forever. Some say it's both. But no matter how you look at it, there's no doubt that debate itself is reshaping our transportation culture.

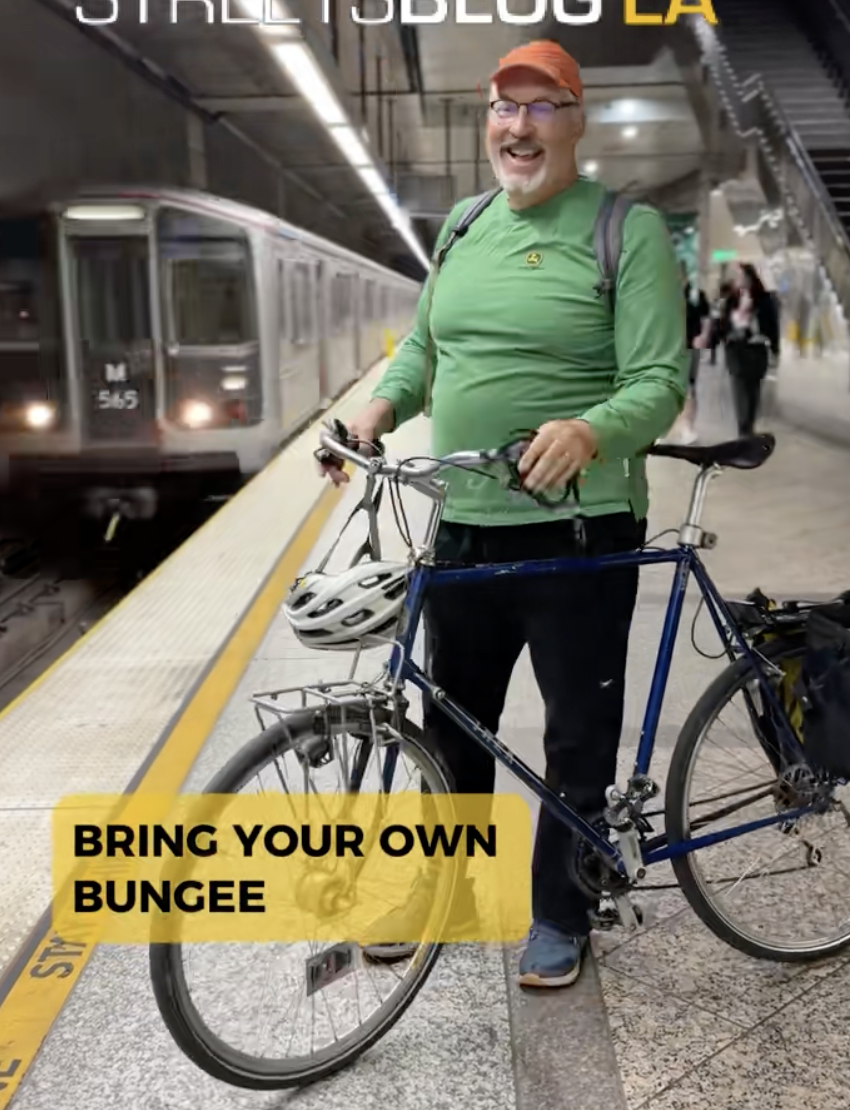

Transportation reporter Alex Davies won't wager a guess when a fully autonomous vehicle will arrive. But in his new book, Driven: The Race to Create the Autonomous Car (Simon & Schuster), he does offer a telling glimpse into the surprisingly recent origins of the industry, which some think is poised to rapidly upend our transportation landscape in the coming years — and some worry will kill even more vulnerable road users if it's allowed past the starting gate too soon.

Beginning with a massive, government-funded robotics competition that sent some of the nation's top scientists scrambling to send Lidar-equipped Humvees and motorcycles racing across the Mojave desert — and ending in a federal prison sentence for one of the industry's most celebrated engineers (though that story got a surprising epilogue on the last day of the Trump administration that didn't quite make it into the book) — Driven is an epic and sprawling adventure. But for street safety advocates, it's also a rare invitation into the psychology of the people who would replace the human driver will a robotic replacement, no matter the cost.

We spoke with Davies via phone. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Streetsblog: Tell us a little bit about the genesis of this book.

Davies: I was working at Wired covering transportation and technology when I started the book back in 2017, which meant that I was often covering self-driving cars from day-to-day. Those were the peak hype years for AVs, and of course. I’d always ask people how you’d get into this field. A lot of them would say, "Well, I went to the [Defense Advance Research Projects Agency] Grand Challenge in 2004." So I did an oral history project on the Challenge for Wired, and every person I talked to had these crazy stories about these races in the desert. I thought, there’s so much here that I couldn’t fit into that article; it was clear that this is a really seminal event, the origin story of a whole new industry.

SB: Why, exactly, do you think the U.S. government and so many companies have poured so many billions of dollars into the development of AVs? And more broadly, why do think human beings are so obsessed with creating cars that can drive themselves?

AD: The desire to develop the autonomous car really was synchronous with the invention of the automobile. Even the horse and carriage was a semi-autonomous vehicle, when you think about it. A horse won’t crash into a wall even if the person holding the reins isn’t paying attention. And then of course, with the invention of the horseless carriage, car crashes started happening immediately, and people wondered, also immediately, how we could eliminate crashes while still maintaining access to this new technology.

But the real funding push that came in the 1960s and '70s — and especially in the '80s, when you saw the first serious efforts to build AVs that worked with the help of sensors — that push came from the military. Especially as weapons technology evolved, our government wanted to get soldiers out of harm’s way by taking the people out of military vehicles in war zones. The thing that really got the DARPA races going, though, was Congress, in its final military funding in Bill Clinton’s last term, slipped in this one little line in the bill was that said, by 2015, one-third of military ground vehicles should be self-driving.

At the beginning of the DARPA challenge, I certainly don’t think people were talking too seriously about street safety, or really about civilian applications of AVs at all. It wasn’t until the third DARPA challenge — what they called "the urban challenge" — that they even started thinking about taking these things into a place where people might walk. The thing that got a lot of the characters in this book into AVs wasn't saving lives, but just the interesting, cool nature of the challenge itself: just the idea of taking a robot into the Mojave desert and letting it drive around over this treacherous terrain on its own. Unsurprisingly, there’s a pretty heavy overlap between people who competed in the show Battle Bots and people who took part in this competition.

SB: Did road user safety become a bigger factor once private companies started thinking about ways to commercialize this tech?

AD: Even when Google came on the scene [with its autonomous vehicle development initiative Project Chauffeur in 2009], no one really mentioned street safety much. Their primary motivation was simply that there’s a lot of money in the transportation space. The story of the tech industry in the 2010s, really, was the story of tech getting into mobility.

That said, I do think that some engineers were genuinely motivated to save lives, at least a certain point. They know how many people die in car crashes every year; they know how much congestion eats into our economy. But their motivations for building AVs are all different, and yes, in some ways, there are competing motivations.

SB: A lot of street safety advocates feel strongly that even a perfect autonomous vehicle wouldn't be worth the billions of dollars it would take to develop it because we know how to end traffic violence without it. The two cities that have actually ended traffic deaths already, Oslo and Helsinki, achieved Vision Zero with good road design and good policy alone, rather than AVs.

AD: I really sympathize with that view, and I do think cities should be doing more with really basic tools like sidewalks. I'm a big fan of the speed bump in front of my house! [Laughs.] But I think to answer the question of why AVs are worth it, you have to tease apart the broad notion of street safety as a whole, and the specific areas of our road network where so many traffic deaths happen: on highways, at high speed. For people inside cars, autonomous vehicle technology could save a ton of lives. I don’t think it’s the greatest tool for saving a lot of pedestrian and cyclist lives.

And I guess the other part of the answer is: why can't we do both? Why not develop great AVs for use in limited situations, and build a lot of sidewalks?

The fact that we seem to have unlimited billions to dump into this far off dream of self driving cars but practically nothing for solving our real transportation problems, which are policy related, right now bodes poorly for us.

— Angie Schmitt🚶♀️ (@schmangee) January 26, 2021

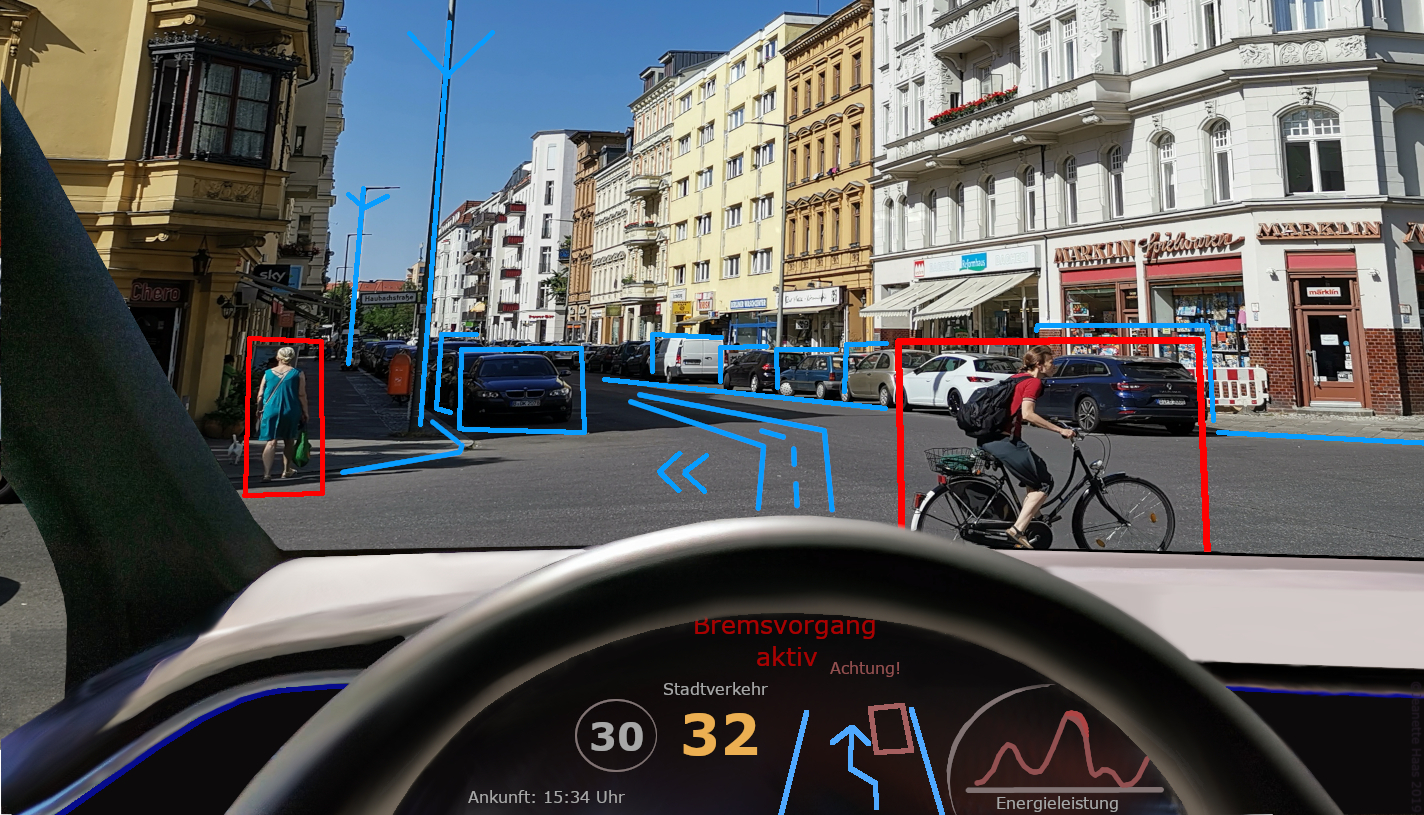

SB: Why, exactly, is it so hard to build a self-driving car that stops for pedestrians, cyclists, and people who use assistive devices?

AD: It’s hard because cities are such dynamic places. City streets work based on human relationships, right? Say four cars come to an intersection at the same time; as a human driver, you have all these choices available to you. You can wave another driver on; you can wave a pedestrian forward; you can hesitate a little longer before you roll foward if that pedestrian is a little kid and you're worried they might dash into the street. You can make all these nuanced choices. Those things are really, really hard for robots.

So much of the problem with roadway safety is that humans are good at things that robots are bad at, and vice versa. Humans are horrific at always paying attention — we are almost physiologically incapable of doing that for a long time — but we’re really good at communicating with one another. Robots are terrible at communicating [with people], but they’re often great at sensing their surroundings, and they're getting better at it all the time. But it’s still really complicated for a robot to figure out what’s a person, what’s a tree, what’s a person standing on a curb looking at their phone. It's a little easier for them, in a highway context, to say, "That's a guard rail, that's a lane line," but our cities are so much more complex than that.

SB: One of the big fears about AVs that I hear from pedestrian advocates is that if autonomous cars become the norm, we'll try to make cities less complex to make it easier for autonomous cars to navigate them — and that will be really bad news for people who don't drive.

AD: Oh, I’m sure the people designing this vehicle would love to have a cleaner street design; good lane markings, clean crosswalks everywhere, and yeah, heavy enforcement of jaywalking rules so no one darts into the street. AV-only lanes are something that I hear a lot of chatter about. I obviously don’t think that’s what’s best for a city, or what’s best for everyone who lives in a city; it’s certainly not best for cyclists and pedestrians. There’s limited space on a city street, and any space you give to AVs is space you’re taking away from people.

SB: The subtitle of this book is "The race to create an autonomous car," but no one has actually won that race yet. Do you think that will happen in our lifetimes? And if someone does win, what might that mean for our cities?

AD: At the risk of being naïve, I do think AVs will happen in our lifetimes. I won't predict a date, because who knows? [Laughs.] But there’s enough evidence that this technology is working in real world situations today. Waymo is taking people out of cars, albeit in a 50-mile area of the calmest Phoenix suburb imaginable. You've got companies like Voyage and Optimus ride looking at places like large senior living communities that have a lot of residents who either can’t or shouldn’t drive, but still need to go to the doctor or the pool or the community center, and they're exploring giving them a low-speed autonomous option. The technology has just come so far in 15 years.

And more important, among the people I follow in this industry, a lot of the hubris has been wiped away. They know it’s going to be harder and more expensive than they thought. But the fact that people are still working on this gives me a lot of hope.

But when it comes to what AVs might mean for our communities — like any technology, they have the potential for good and for bad. Creating it alone is not enough; we also have to decide what it’s used for. And that should be up to everyone — regulators, yes, but also, the people who live in cities where AVs will drive. And it shouldn't just be up to the companies who make these cars.

For more info on the book, click here on the publisher's website.