Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Telecommuting, work from home, telework: the idea that people could eliminate the work commute entirely on at least some days of the week has long been considered one key strategy to fight traffic congestion, cut car trips, and help meet climate goals to lower greenhouse gas emissions.

Californians seem to be in the middle of an experiment to see whether it can work - certainly many people are experiencing the benefits, and drawbacks, of working from home right now. Even those who don't have the kind of job that can be done from a kitchen table have been experiencing less traffic congestion and faster trips.

So it's understandable for people to speculate what this could mean for planning, if it could be sustained, and the last few weeks have seen new thought pieces almost every day about the promises and challenges of telework. Widespread telecommuting could cut car trips and greenhouse gases - or it might kill cities. It could drastically change the need for commercial office space or reduce the number of cars people own. It could expand job opportunities for people living in smaller, less central cities, moving wealth away from coastal elites.

Maybe.

It's important to remember that this current accidental experiment is very limited in scope - and therefore so is what can be learned from it. The pandemic hasn't just kept people home - it has shut down large parts of the economy. With so many businesses closed, there's no way to know what general effects telecommuting might have on traffic patterns, housing choices, trip making, or any of the myriad issues upon which speculative eyes are being trained.

A recent conversation with Ellen Greenberg, who heads up Caltrans' Sustainability Office, came about because she mentioned some of these limitations at a recent California Transportation Commission meeting. Greenberg told the commission that the potential benefits are large, and several regions are exploring ways to encourage telecommuting. The Bay Area's Metropolitan Transportation Commission, for example, has floated a telework tax credit for those who choose to work from home. The Sacramento regional government has proposed a regional plan to accelerate broadband deployment, and the San Diego region has considered incentives and technical assistance to support the development of telework policies and programs.

However, said Greenberg, Caltrans is also discovering that the complexities involved make it more difficult to get the benefits telecommuting seems to promise, including less congestion and fewer vehicle miles driven (VMT).

That is because past research seems to show that more telecommuting may not lead to less driving.

People who telecommute may in fact end up driving more than people who have to drive to work. They may take extra car trips, like driving to lunch or taking the dog to a park. They may drive children to and from school, making several round trips instead of one drop-off on the way to work. On days they do go to work, their work trip might be much longer, since they are freed of that daily trip and may live farther from work - and that could add up to more miles driven in total.

In addition, Sam Speroni, a UCLA graduate student who is preparing a research review for Caltrans, has found very little consistency among pre-COVID research results. These have generally been based on limited data samples and usually focused on very specific questions such as environmental benefits, worker productivity, or potential technologies.

"I have been surprised at a number of things I've been learning," said Speroni. "One is how incoherent and inconsistent existing research is. You could find a study that comes to one conclusion, and a different one that says the opposite."

"Another is the attention telecommuting gets, relative to the size of it," he said. Telecommuting has never been a big part of the commuting picture, according to Speroni. About five percent of the U.S. workforce has a "zero-mile" commute, according to census data, and that includes everyone from residential farmworkers to home businesses, and even fishermen. Telecommuters are among them. In California, that small percentage has held steady for the last forty years or so, and while the absolute number may have grown, it remains a small percentage of the workforce.

"There isn't enough information to make a clear statement about, say, part-time telecommutes, or health outcomes," said Speroni, naming two more speculative points that have been brought up.

The giant decreases in traffic we've seen during the pandemic - in some places 75 percent of traffic disappeared - cannot be explained by telecommuting alone. Since businesses and schools are largely closed right now, even shopping trips have been reduced or curtailed, and others are just gone for now.

Also, the number of jobs that even have the potential for being done via telecommuting ranges from between one quarter and one half of all jobs, at most, depending on who's measuring. But that doesn't take into account home and family circumstances or worker and employer preferences.

"Within Caltrans, there's been an amazing shift," said Greenberg. Before the pandemic, despite some encouragement, telecommuting had very low adoption rates among the almost 21,000 people who work for the department. "But we found that we could do this," she said, and at one point almost ninety percent of Caltrans office employees - which are maybe two-thirds of their work force - were working from home.

That involved a number of challenges, including making WebEx meetings work, but also, for individual employees, finding adequate work space at home, ensuring fast enough internet connections, and avoiding distractions from children, partners, and pets who were also sheltering at home. It's all very familiar to many people now.

It's good to know telecommuting is possible, at least for some, but it remains to be seen whether it is overall a good thing. Whichever is the case, the dramatic changes in traffic levels that have occurred in the past few months don't really represent what life might be like in "normal" times, whatever that will mean in the future.

"New trip making habits are likely to emerge," said Greenberg, "so telework does not 'zero out' VMT." In general, people have a kind of mental travel budget - how much time they are willing to, or want to, spend traveling. For many years researchers who have studied this have pinned the "ideal commute" at about twenty minutes. That goes for car, transit, bike, or walking commutes - people generally seem to like about a twenty minute distance between home and work.

Also, "people are accustomed to using that time for driving," said Greenberg, and although not having to drive in rush hour traffic could be a huge stress reducer, it doesn't mean people don't want to drive at all. In fact, they may shift their driving to a different time. That has implications for traffic congestion, if it means lower peak-hour traffic volumes (and potentially higher off-peak traffic), which is not a bad outcome. But it means little for reducing VMT.

Other questions that cannot be answered just by looking at pandemic-time data include:

- School trips: Will school be in session? Will people drive their kids to school, if it is?

- Shopping: Will people shift to online shopping? Will that increase delivery truck trips, and thus VMT? Greenberg points out that delivery times are also important, because shorter promised delivery times tend to lead to less efficient, more mile-inducing deliveries.

- Health and active transportation: People can become more sedentary if they work from home and their commute is reduced to a few steps between a bed, a desk, and a fridge. This highlights the importance of making biking and walking trips an attractive option, both for mental breaks and for errands, shopping, and delivering children to school.

- Land use: Much has been written about the potential for people to move away from expensive cities if they can work from farther away without the penalty of high rent. But people like being in cities. If they can stay, will they? Many young people have been forced to move back home to ride out the pandemic - but will they want to stay in town if they don't have to?

- Office space: Companies certainly could save money on office space and utilities if their employees stayed home, but that would simply transfer those costs to the workers. Not everyone has a spare room, or enough privacy, at home.

- Preferences: Some people like to work from home, and some people would rather not. For some, it increases their quality of life, and for others it is fraught. Home circumstances have a lot to do with this, but so do things like time spent grooming, and the perception of having options.

- Induced travel: Generally, when roadway congestion eases up, then more people choose to drive. Over time, it seems unlikely that trip reductions due to workers telecommuting won't just be replaced by other driver trips.

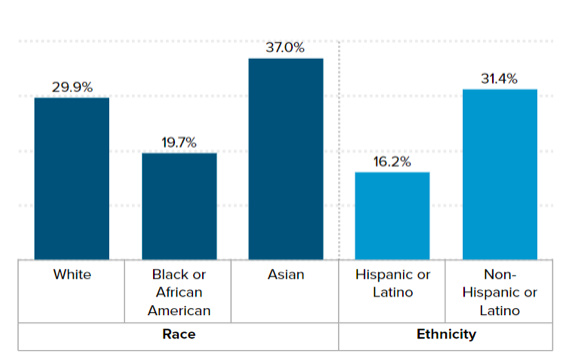

- Inequities: Only some jobs are even possible to do as work-from-anywhere jobs, and they tend to be available only to affluent white people. How would this be addressed?

"Also, this doesn't consider the role and structure of transit," said Speroni. Rail transit in particular has a role to play in telecommuting; pre-COVID telecommuters tend to use rail on their infrequent commutes, which speaks also to their generally higher incomes. In general, it is oriented towards downtowns, where the jobs tend to be. But most transit is also oriented towards commute trips. If those were to go away, would it come to seem overbuilt? Or maybe it would it need to play an even bigger role, to encourage more part-time telecommuting?

One thing is certain, and that is that the answer is unknown. Ask again later.