A new nationwide study suggests that people living in neighborhoods with higher levels of fine particulate air pollution are more likely to die from COVID-19 infection than patients who live in areas with cleaner air.

The frightening data from Harvard's T.H. Chan School of Public Health is especially concerning in California, where the people living next to highways, major roads, and polluting industries--and thus subjected to higher levels of pollution--tend to be low-income communities of color.

The Harvard study compares county-level COVID-19 deaths (as of April 4) with each county’s long-term average concentrations of pollution particles smaller than 2.5 micrometers in diameter, also known as PM2.5 or “fine particulate” pollution. The authors found that counties with just one more microgram per cubic meter in their average fine particulate levels had, on average, a fifteen percent higher mortality rate from COVID-19.

The results “underscore the importance of continuing to enforce existing air pollution regulations to protect human health both during and after the COVID-19 crisis,” write the study’s authors. Note, however, that the U.S. EPA has decided to follow exactly the opposite course, and has used the pandemic as an excuse to suspend enforcement of existing regulations.

The study results also underscore the importance of addressing the historical injustices that have put some Californians in a more vulnerable position for all health outcomes. We already know that rates of asthma are higher in many low-income communities of color; we know that air quality is worse in some places in the state than others, and that many of those places are home to disadvantaged communities. It is just another thumb on the scale for these communities that they are more likely to suffer the worst consequences of COVID-19.

State policies on climate change, air quality, and transportation planning address this inequity, although usually as an afterthought. For example, via hard-fought, single-issue legislation that calls for better local air quality monitoring, or broader representation on state decision-making bodies, or via higher scores for transportation projects that benefit disadvantaged communities in one funding program, the ATP.

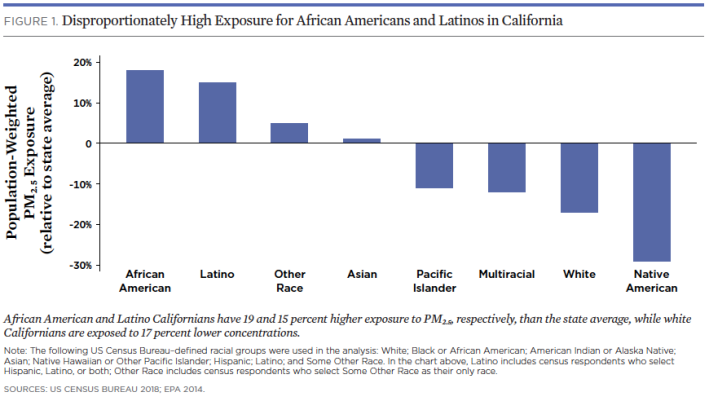

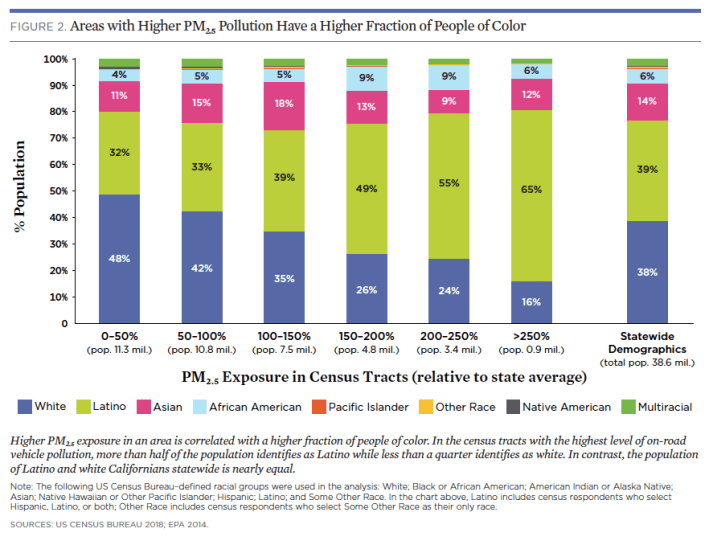

A 2019 report from the Union of Concerned Scientists [PDF] found that residents in the counties of Los Angeles, San Bernardino, Orange, San Diego, Fresno, and Kern had higher-than-state-average exposure levels to particulates.

That study also found that African American, Latino, and Asian Californians are exposed to more particulates from cars, trucks, and buses than white Californians. The lowest-income households in the state live in areas with particulate rates that are ten percent or more higher than the state average, while the highest-income residents enjoy pollution rates that are thirteen percent below the state average.