Caltrans hosted a webinar recently to discuss changes it will be adopting soon in the way the department measures, analyzes, and mitigates for the environmental impacts of transportation projects on the state highway system.

The department acknowledges that its current practices have not solved urban congestion and instead have led to more driving, more emissions, and unsafe conditions for people who don't drive.

The policy changes are in response to S.B. 743, which was passed in 2013 but has taken years to develop into practice. That law required the state to find a better way to measure the environmental impacts of transportation than by measuring vehicle delay. Until recently, agencies accounted for environmental impacts by analyzing Level of Service, or LOS, which looks only at how much delay a project would cause vehicle traffic. There was no analysis of how much new driving might occur.

To address the resulting auto delay, projects were required to widen roads and intersections to allow more vehicles through faster. Those mitigations made driving easier and faster, while the experience and safety of other road users was ignored.

Result: more driving. "This widespread response to new capacity is the reason we have been unable to reduce congestion in urban areas for more than a short time," said Chris Schmidt, who manages Caltrans' S.B. 743 program and led the recent webinar.

Two kinds of projects are subject to new rules under S.B. 743: Land use projects, which Caltrans weighs in on if they affect the state highway system, and transportation projects, for which Caltrans serves as the lead agency if they are on state highways.

Land use projects will be required to use the new measure, vehicle miles traveled, starting next July. Some cities, notably Los Angeles, Pasadena, San Francisco, and San Jose, have already adopted the measure in their planning practices.

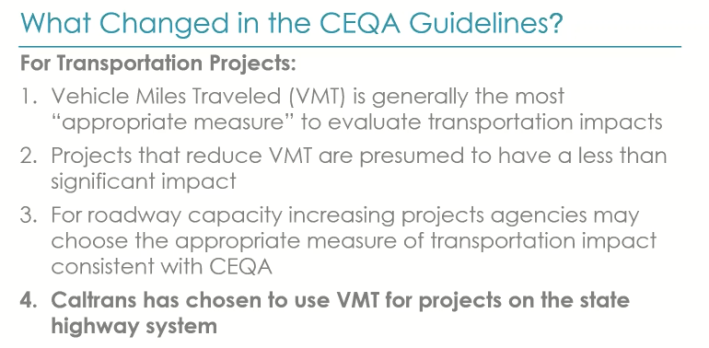

The Governor's Office of Planning and Research (OPR), which developed the guidelines for S.B. 743, gave lead agencies some leeway on highway capacity projects, saying they "could choose the most appropriate" way to measure environmental impacts.

Caltrans says it has decided that vehicle miles traveled (VMT) is generally the most appropriate measure to assess the impacts of transportation projects.

"These changes are profound, and will challenge the state of practice for all of us," said Schmidt to the more than 400 practitioners--city planners and engineers, Caltrans staff, and consultants--who were listening to the webinar.

Until recently, Caltrans has resisted acknowledging the concept of induced demand, which shows that building new roads and widening existing ones does not reduce congestion but in the long term--sometimes even in the short term--just adds more cars to the system.

California cities are beginning to understand that there is no room for more cars in the system. And state agencies are starting to acknowledge that reducing greenhouse gas emissions will require reduced driving, not just shifting to renewable energy. But as long as agencies continue to try to solve congestion by adding roadway capacity, driving will increase.

Note that not every last transportation project is subject to Caltrans' new rule. For example, most of the projects in the State Highway Operation and Protection Program will not be subject to it, because most of them focus on maintenance and rehabilitation, rather than increasing capacity.

Caltrans is still working out the details of these new policies, including when they will take effect. While the land use projects must begin using the new measure by July, no date has yet been set for transportation projects. It is a cause for concern among planners and agencies who are planning future projects, a process that can take years. According to Schmidt, "Caltrans has been working on the best date to begin, and intends to have further discussions to set a date in the near future."

Another key aspect that will require more work is the question of mitigation. Under the California Environmental Quality Act, agencies must analyze environmental impacts and find a way to mitigate what they can. As pointed out above, under the old system that mitigation took the form of wider and faster roads, to avoid delay. But VMT is harder to mitigate.

Schmidt mentioned some potential measures, including supporting people who shift from cars to other modes like biking, walking, and transit; supporting higher occupancy vehicles; mitigation banks, which could create a way to trade mitigation offsets; and transportation demand management policies. "Caltrans is committed to developing robust mitigation strategies," said Schmidt, and recognizes that it will need partners in that effort.

It's important to note that these measures are key to reaching state climate and health goals. Unless they truly are robust, and include strategies like parking and congestion pricing, automatically including complete streets elements in every project, planning and building better biking and walking infrastructure, and investing in transit operations and service improvements, they will just be a waste of time.

OPR has done extensive work on the question of mitigations -- a lot of research is collected together on its website here -- and Caltrans says it is committed to using the OPR guidance in its own documents.

The department is continuing to develop guidance on mitigation as well as on how to conduct the transportation analysis, on methods for calculating vehicle miles traveled and induced travel demand, on determination of impacts under CEQA, and on measuring and determining greenhouse gas emissions.

Draft documents should be available in early 2020, with a four-week comment period. More webinars are planned during that time; more information here, as it becomes available. Caltrans plans to release its final guidance in spring or summer of 2020.