Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Anticipation for the opening of the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge to bikes and pedestrians this weekend is running high. This major transportation facility has, until now, been an impenetrable barrier for people not in vehicles. Starting Saturday, it will finally be accessible to people without a car.

There has been a lot of back-and-forth in the past few years about the path. Some people, particularly press and politicians in Marin County, can't see the point of dedicating the space to bike riders or pedestrians. They continue to argue that this "pilot project" should be summarily ended, the sooner the better, so more cars can clog the bridge. MTC is studying the feasibility of making the path part-time only.

But others have been waiting for this path for over twenty years -- for so long, that it almost seems unreal that it will really happen. By some counts, the fight for the path has gone on for closer to fifty years, ever since one of the bridge's vehicle lanes was closed to install a pipeline so the East Bay could deliver water to Marin County during the drought in the 1970s. When the drought ended, the pipe was removed, and the third lane was set aside as a breakdown lane.

Bike advocates asked for, but didn't receive, access to the bridge at that point. Caltrans provided an unofficial shuttle to carry riders and their bikes across, and expected riders to be satisfied with that.

Then, a little more than twenty years ago, everything shifted. Caltrans cancelled the shuttle, for one. The only remaining way for bikes to cross was via a single bus, Golden Gate Transit's Route 40, which could only carry two bikes at a time and didn't cross frequently.

That was during the summer of 1996. That fall, Robert Raburn of the East Bay Bicycle Coalition--which had originally been founded in 1972 to fight for bike access on BART--organized a ride to protest the lack of access on the Richmond bridge.

"We gathered at Richmond Bart and biked about twenty minutes, some of which had to be done on the freeway," local bike advocate and activist Jason Meggs told Streetsblog. "I have a photo somewhere of a wall of CHP. Raburn has his hand out, with his finger pointing, and he's telling them: 'There is nothing in California state law that prohibits us from biking on this shoulder.' The cops had nothing to respond, so they gave up and left."

"They obeyed him!" said Meggs. In his history of advocacy, Meggs had "seen some terrible things where the cops didn't help, where laws didn't help. My faith in the system was very low," he said. Raburn's clear understanding of the law, and insistence on it in the face of the police, "really inspired me," he said.

Meggs knew biking on the bridge was possible, having done it a few years previously on a trip home to the East Bay from Seattle. Inspired by the EBBC ride, he decided there should be a protest ride every month.

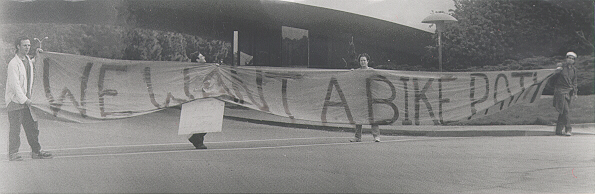

For the next several years, Meggs and others organized rides to the bridge that sometimes ended at the toll plaza and sometimes went further. They rode the freeway to get there. They argued with the CHP and Caltrans about whether they could hoist a banner.

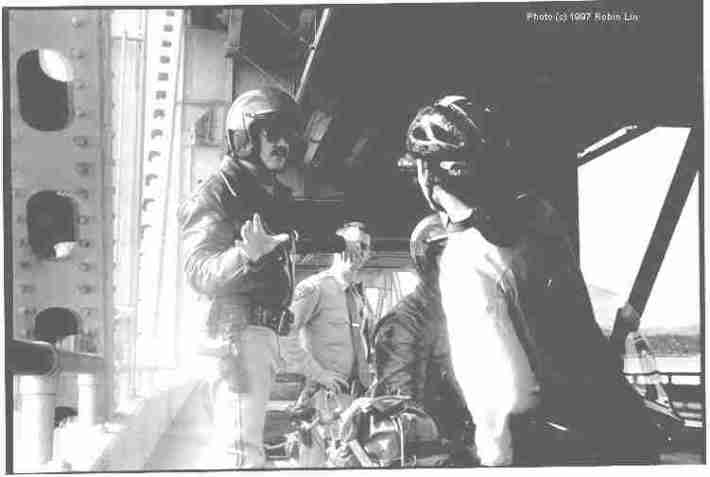

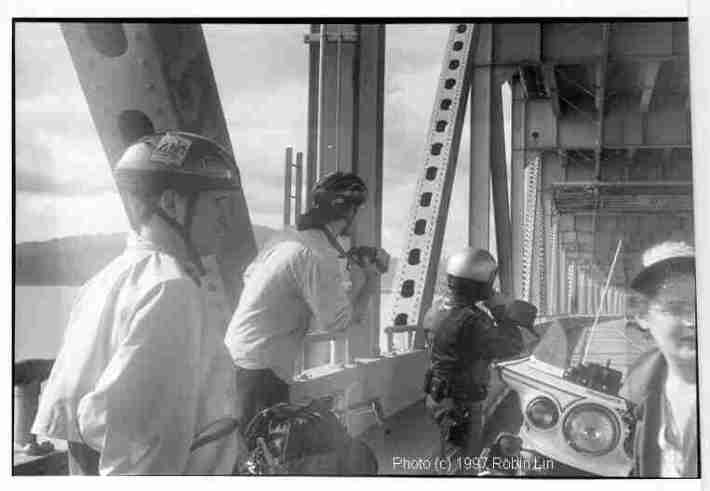

After exploring the entranceways, five of us decided to go over the top deck. We slipped inside the 'Jersey barrier' separating the construction crew into the side lane (gee, so this is what a separate bike path would feel like!) and rode past the construction workers ("You're crazy" said one of them) and up the bridge. WHAT A VIEW !!!!!!!!

Meggs and others were busy putting information out via the early internet--in which graphics took forever to load, if they did at all, and home computers were nascent. Word of mouth was key, so Meggs made flyers and passed them out at Critical Mass rides, which were taking place monthly in San Francisco but also in Marin, Walnut Creek, Silicon Valley, Alameda, Oakland, and other places.

There was a lot going on in those years, from 1996 to about 1999. San Francisco's Critical Mass was exploding, and the police and then-mayor Willie Brown tried to quash it. Their efforts backfired, though, when they arrested bike riders and the response was even larger numbers of bicyclists showing up to demand fair treatment and space in the street.

At the time, bicyclists were organizing for access on all the Bay Area bridges, including the Oakland Bay Bridge (ultimately successful, halfway, so far) and the San Mateo bridge (ultimately unsuccessful, but not quite dead yet). Meggs founded the Bike the Bridge! Coalition, which organized protests and several wildcat rides across the Bay Bridge long before there was a bike path on it. Among the things they learned on those rides: The tunnel was rideable, and "The Bay Bridge West Span has the best view in the Bay Area that can only be truly appreciated from bicycle, not from automobile."

Meggs also founded the Bicycle Civil Liberties Union to help support bicyclists caught up in legal issues or fighting unfair tickets, and to fight for safer conditions and justice for bicyclists. He developed a guide to fighting a bridge biking ticket using the vehicle code.

Other bike advocacy organizations were forming, and growing, including the Marin County Bike Coalition founded by Deb Hubsmith, a staunch advocate of bike access on the Richmond Bridge.

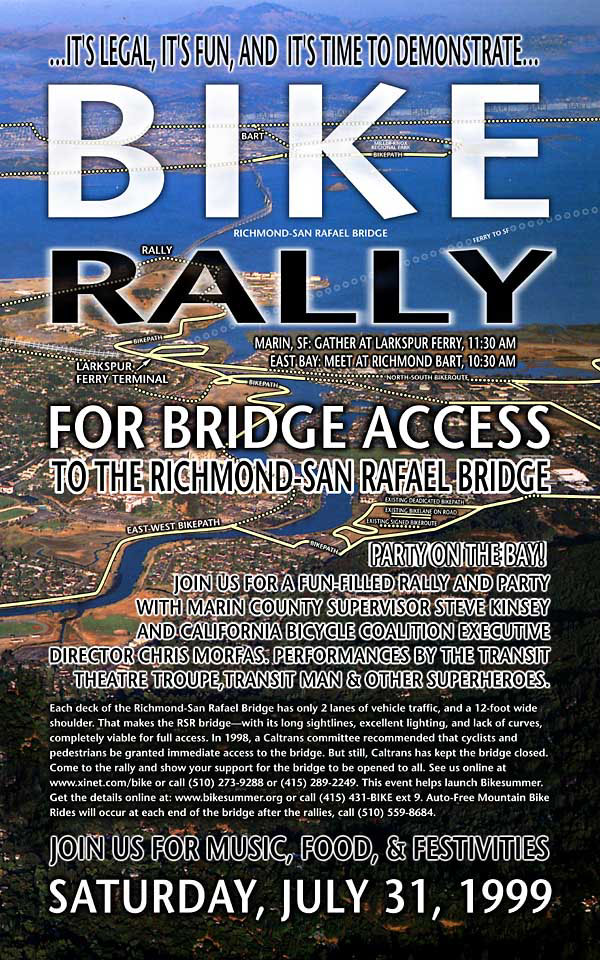

In 1999, Bike Summer came to San Francisco, and with it people from all over the world.

"We held major events in Berkeley and at the Richmond Bridge," said Meggs. They organized a "major assault" ride to the bridge, where, said Meggs, "We had a giant crowd on both sides, brought people out on buses."

But a flyer from the July ride that year reminded participants that:

We are not advocating doing anything chaotic or risky such as storming the roadway of the bridge itself, or blocking traffic on the bridge (despite the fact that Caltrans has been blocking legitimate and imperative bicycle traffic on the bridge for more than 20 years in violation of every principle and even their own policies!).

The various groups held protests at the MTC, deriding the minuscule amount the state spent on bike infrastructure. They circled the agency with Sport Utility Bikes, basically bikes surrounded by lightweight frames that made them take up as much room as cars. "That was fun," said Meggs. "They would sway as you went around corners." They gathered signatures on petitions and created a pledge drive for cyclists who said they would use the bridge path every day, and drafted resolutions for Marin County and the Berkeley City Council in support of bike access on the bridge.

But the efforts weren't limited to protests and publicity, photogenic as they are. There were also lots of meetings with state agencies and local jurisdictions. Advocates drafted potential designs for what a bike path could look like, and addressed problems would need to be solved.

Caltrans had begun the process -- some years after the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake -- of planning a seismic retrofit of the Richmond Bridge. To complete it, the department needed a permit from the Bay Conservation and Development Corporation, a regional body that oversees any development within 100 feet of the Bay.

So advocates, including Raburn, Meggs, Hubsmith, Dave Campbell of the EBBC, and others, attended BCDC meetings around the region to argue for bike and pedestrian access. They had several key state laws in their favor: The McAteer-Petris Act of 1965, which made the Bay Conservation and Development Commission a permanent state agency, included a section that requires projects to provide "maximum feasible public access" to the shoreline and waters of the San Francisco Bay.

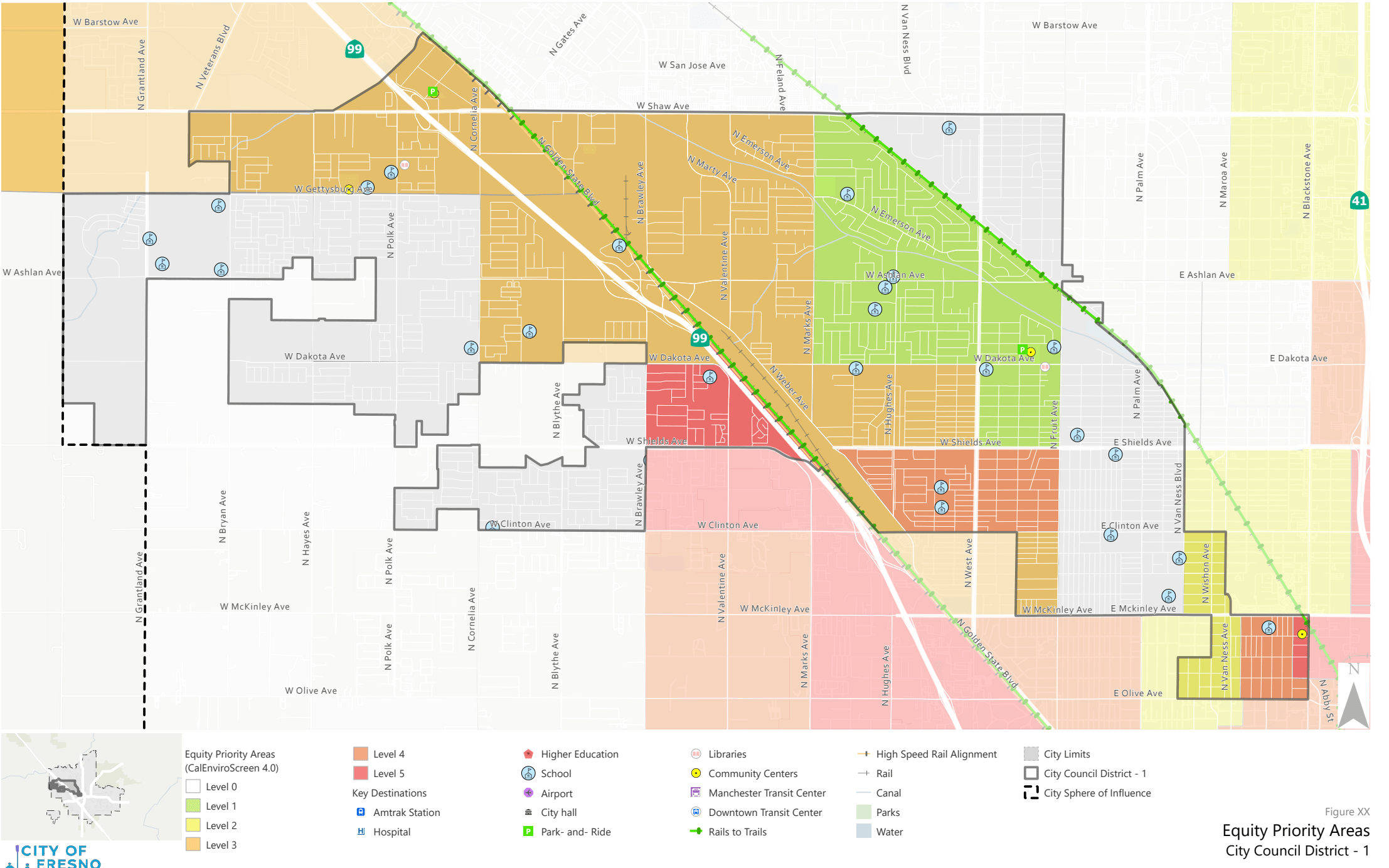

The Richmond Bridge was also identified as a key link in the San Francisco Bay Trail, a vision for a 500-mile bicycle and walking trail circling the entire bay that was first proposed in 1989. So far, 350 of those miles have been developed, and Saturday's opening of the Richmond Bridge will close a critical gap.

For several years, the advocates attended BCDC meetings around the region, arguing that any permit given to Caltrans to retrofit the bridge should require bicycle and pedestrian access. They had the support of many of the BCDC commissioners,but Caltrans fought back.

Some of the arguments used by Caltrans and others at various times against building a bike path included:

- Cars need thirty feet of clear recovery area, and Caltrans was liable if they didn't provide it

- The bridge deck is filled with expansion joints, which could catch a bike wheel and seriously injure a rider* (Meggs researched the issue and found an off-the-shelf steel grate that could cover them, sliding with the movement of the joint)

- Bridge operators need the shoulder to be available for maintenance and repair and crash recovery and breakdowns

- It would cost too much

- The bridge was too narrow for a bike lane and they'd have to build a whole new structure

- A barrier between path users and cars would be unsafe, because "cars could hit it and bounce off and into other cars" and drivers could feel "closed in"

- BCDC had no authority to require access

This last idea was put forward by Caltrans, and backed up by then-Attorney General Dan Lungren, and although there was disagreement on whether it was true, the BCDC decided not to fight. Meanwhile Caltrans was putting off advocates by agreeing to a feasibility study.

That produced a recommendation in favor of bike and pedestrian access, so Caltrans called for another study. Ultimately three different studies were done, with Caltrans rejecting every conclusion that called for bike access on the bridge.

Eventually advocates were distracted by other efforts. The energy of Bike Summer and Critical Mass faded away, and the issue was set aside.

It wasn't until 2013 that the idea was resurrected, and this time it was MTC that brought it up. At the time, the regional body was considering reconfiguring the lower deck of the bridge -- the one leading out of Marin -- to add one more vehicle lane. Perhaps because of the tenaciousness of advocates in the earlier fights, or maybe because of all the work they put into the feasibility studies and designs, but this time around the powers that be also suggested that the top deck might be reconfigured to accommodate bikes and pedestrians.

The fight of the last few years has been very different from the earlier ones. Reconfiguring the bottom deck was expensive, requiring moving a tall retaining wall to widen the eastern end of the touchdown, but it was finished last year. Progress on the upper deck was much slower, although it comparatively simple, requiring cleaning up the approach to the bridge, adding a barrier on the freeway and the bridge, and making sure those expansion grates were covered. Meanwhile the press in Marin continues to claim that no one will ride it, and the pilot should be terminated quickly. Others strongly disagree.

Even in the face of the urgency to cut emissions, knowing there is so little time left to change the way we plan and fund and build for transportation, there are still people advocating hard for more space for cars.

"It's taken generations to win this access," said Meggs recently. "What's really inspiring about this victory is it proves that determination wins -- and there has never been a time to be more determined than now."

"The tide is clearly turning when after nearly half a century of intransigence, our most promising and viable form of individual mechanical transport is finally allowed to use our most important public highways," he added. "The droughts of yesteryear brought us this option, and the fires of today make it beyond imperative."

Big crowds are expected at Saturday's opening. The Richmond San Rafael Bridge will actually become a bridge, rather than a barrier, for people like Nakari Syon of Rich City Rides, who says he has been "shadow-boxing Mount Tam my whole life."

But the lessons from those early fights for access should be kept in mind, because until those who clamor for more vehicle access get out on a bike and ride the bridge themselves, the fight is not over.

*This dire prediction came true with tragic outcome a few years later when Alex Zuckermann, the founder of East Bay Bicycle Coalition, had exactly this happen to him when he accompanied Caltrans engineers on an exploratory bike ride of the unfinished path on the Oakland Bridge. He later succumbed to his injuries.