On Monday, July 8, the Assembly Transportation Committee will consider S.B. 127, the Complete Streets bill from Senator Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco).

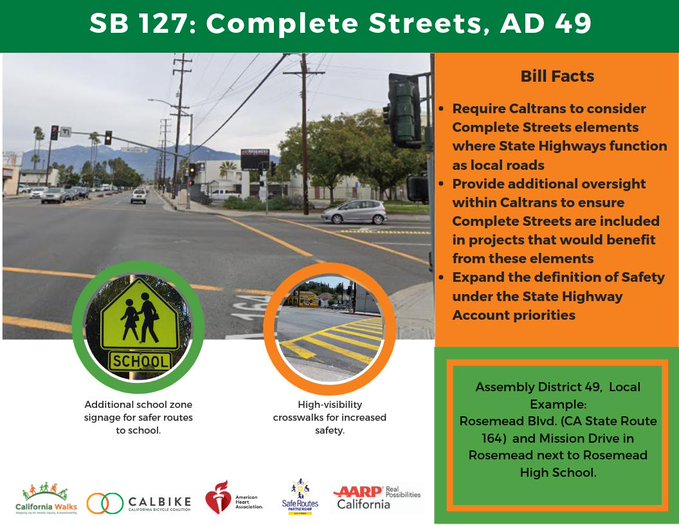

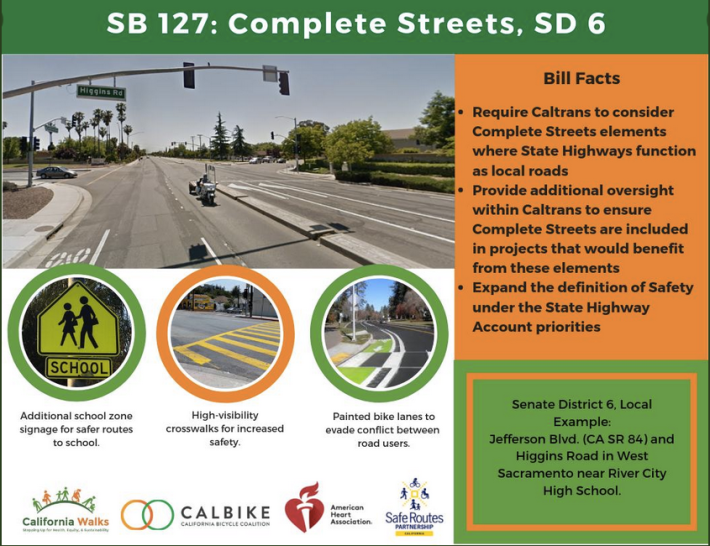

The bill would require Caltrans to include safety improvements for people on foot, on bike, and taking transit whenever it performs road maintenance in certain defined areas: on state-owned highways that are not freeways but are within cities or "census-designated places." The bill's author estimates that this is about seventeen percent of the state highway system, and includes city streets like San Francisco's 19th Avenue, Jefferson Boulevard in West Sacramento, and Rosemead Boulevard in the San Gabriel Valley.

The bill passed the Senate, but faces a potential obstacle in the form of the Assembly Transportation Committee chair. Assemblymember Jim Frazier (D-Discovery Bay) has not been supportive of similar efforts in the past, and at times has been actively hostile to some of the concepts in the bill--specifically provisions that call for a consideration of the equity consequences of road projects. He may push for amendments that weaken the bill.

This post, and one to follow tomorrow, will take a close look at the current language for S.B. 127 and why each of its provisions matter.

I. Baseline

S.B. 127 begins by stating that the state legislature "finds and declares" certain basic information about active transportation in California. For example, that walking and bicycling trips doubled between 2000 and 2012, and already constitute nearly twenty percent of all trips in the state.

The bill also notes that, in California, people walking and bicycling are killed or seriously injured at much higher rates than car drivers or passengers because safe walking and bicycling infrastructure is lacking. Older adults, people of color, and people walking in low-income communities are disproportionately represented in these traffic deaths. This information is based on data from the National Household Travel Survey and Smart Growth America's report Dangerous by Design 2019.

Caltrans has adopted various goals and policies related to active transportation, for example to triple biking and double walking trips by 2020. The department also has internal requirements to "consider" complete streets improvements when transportation projects are built, and goals to increase the number of complete streets improvements between 2015 and 2020. However, those goals cannot be achieved without significantly improving transportation facilities for people not in cars.

The bill points out that

Some low-income communities and communities of color lack well-maintained routes to parks and schools, roads, bike lanes, and sidewalks for decades. In many cases, those communities simply have no transportation options. The same communities often experience higher rates of chronic diseases like diabetes and heart disease.

And finally, it acknowledges that getting California residents to adopt more active and healthy transportation options "requires the state to leverage its existing resources to get serious about improving the safety of the roadways."

Why is this needed?

Car culture prevents many Californians from understanding that not everyone can or wants to get around in a vehicle. But the result of fifty-plus years of planning, investing in, and building for car-centric transportation has left the state with a system that (not counting congestion, crashes, deaths and injuries, pollution, climate, etc.) works only for drivers, and creates serious safety issues for everyone else.

The above safety stats bear repeating, because many people don't believe them. People tend to blame the victims of traffic violence rather than car-centered streets and roads. It's almost as if it were illegal to walk in some areas because it is so hazardous. Many drivers believe people who ride bikes are just plain crazy.

With serious concerns including declining air quality, health issues, and climate crisis, that status quo has to change. The last thing California should be doing is effectively forcing people to drive cars in order to feel safe or sane.

To make this change happen, a key step would be to take a hard look at the way California invests its transportation money.

II. Track and Manage Complete Streets Assets

"Asset Management" sounds wonky and boring but is a crucial part of making sure that Caltrans and the state move towards better safety outcomes for people walking and biking, and indeed all road users. The assets in question are things like highways, roads, bridges, traffic signals--basically anything that is owned and maintained by the state in the service of transportation.

Caltrans is required to adopt and update plans to manage and maintain its assets in a way that reflects various state goals, including environmental ones. The Asset Management Plan is the basis for determining which transportation projects get funding, guiding decisions about investments in the State Highway Operation and Protection Program (SHOPP), which focuses on repairing and maintaining California's road system.

S.B. 127 requires Caltrans to include active transportation infrastructure--bike lanes, crosswalks, pedestrian crossing signals, and the like--in the asset management plan, and to "develop and meaningfully integrate performance measures" that will help meet the mode shift goals the department already has. Those performance measures include the conditions, number, and type of bicycle and pedestrian facilities as well as measures of accessibility and safety for pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit users.

The bill also calls for transparency and accountability. It requires a process for community input, for example, and calls for Caltrans to develop a "plain language performance report" describing pedestrian and bicycle facilities included in SHOPP projects.

Why is this needed?

Caltrans has the policies and goals in place, so why is legislative action needed? The short answer is accountability.

Look no further than a recent project in Oakland: a new overpass over a freeway. Caltrans calls it a "multimodal" facility and claims that it accommodates all users, including people in nearby neighborhoods who get around on foot and by bike. The project even received an award for "safety improvements" there.

But whoever gave them that award, along with the engineers who built it, must not believe there are children wanting to use the overpass on foot, despite its location near a school. The overpass features wide, fast vehicle lanes and narrow sidewalks. It has a bike lane, but it's narrow, tucked into the gutter, and features dangerous, tire-grabbing grates. On both ends of it, pedestrians are blocked from crossing, and where they can cross, at an inconveniently placed signal, they must wait a long time. Meanwhile the overpass allows vehicles to speed off the freeway and make wide, fast turns without stopping or even slowing much.

That Oakland “Interstate 880 Safety and Operational Improvements" project is not an old moldering piece of infrastructure. It opened in 2019. Caltrans has had mode shift goals and complete streets rules on its books for years, but doesn't seem to take them seriously. This overpass is clear evidence that Caltrans engineers don't follow their own department's policies.

Requiring Caltrans to count, track, manage, and report on active transportation "assets" would force its engineers to reveal exactly what they consider to be "bicycle and pedestrian facilities." Requiring the department to establish strategies to meet its mode shift targets would force them to take a hard look at how road designs affect the safety of people using the road.

Requiring the California Transportation Commission to prioritize safety for bicyclists and pedestrians would mean that projects would have to address those safety issues up front, when they are asking for funding, and cannot just slap on a few sharrows as an afterthought. Instead of widening roads in the name of "motorist safety"--as Caltrans and California cities continue to do--they will have to consider the safety of other people who use those roads, including people on foot or bike.

That could potentially lead to acknowledging that removing a crosswalk because it is "dangerous" for people to cross a busy road is an absurd, ineffective, and dumb way to solve a safety problem.

Follow Streetsblog California on Twitter @StreetsblogCal