Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

An outdated, Orwellian California law requires speed limits to be set according to how fast people drive. That's no typo: the current method for setting speed limits on California streets--in your neighborhood--is not according to what is safe, but, by law, according to the behavior of random drivers seatbelted and airbagged safely within a steel cage. If many scofflaw drivers drive dangerously fast, then municipalities are required to raise limits, resulting in a vicious cycle where more and more drivers speed and streets become more and more deadly.

"Speed limit determinations rely on the premise that a reasonable speed limit is one that conforms to the actual behavior of the majority of drivers," according to the California Manual for Setting Speed Limits. "One will be able to select a speed limit that is both reasonable and effective by measuring drivers' speeds."

"Speed limits... are normally set near the 85th percentile speed, [which is] the speed at or below which 85 percent of the traffic is moving, and statistically represents one standard deviation above the average speed."

That's a little like setting a teenager's curfew based on when teenagers usually come home--and makes some equally big assumptions about reasonable behavior.

And it makes no sense to people outside of cars. For example, say, people walking along Balboa Blvd in Los Angeles' Granada Hills neighborhood. The speed limit on this arterial, lined by houses and strip malls and shopping centers of various sizes, was raised to 40 mph because that's how fast about 85 percent of the people drive. Long stretches of the street have no parking, to allow more traffic to pass, so there is no buffer between pedestrians and speeding drivers.

The excessive speed also makes little sense to drivers trying to pull out of driveways and side roads onto arterials like Balboa.

Speed limits are, of course, not a solution by themselves to the safety issues that come with speeding. Designers and engineers need to build streets that cue drivers to maintain safer speeds. Speed limits also require enforcement. This is problematic in several ways, as most California cities lack resources for significant traffic violations enforcement, and when enforcement is used, profiling often means adverse impacts on people of color.

The state has long been afraid that cities will create speed traps to make money off innocent drivers. To prevent this, California forces municipalities to measure existing traffic speed before they can set any speed limit. Because of the 85th percentile rule, some cities have had to raise speed limits on local streets just to be able to enforce any speed limits at all.

Road conditions or other safety concerns are not included in this equation, and the notion that a city, or Caltrans, might actually try to design a road to force drivers to slow down is taking a very long time for engineers to accept. Instead, "safety" has dictated designing roads, even residential arterials like the above-mentioned Balboa Blvd, to be ever faster, with wide lanes, wide intersections, and signals set to keep traffic moving.

But that doesn't equate to an increase in safety. It's a Catch-22 of epic proportions.

Last year, Assemblymember Laura Friedman was able to pass - and get Governor Brown to sign - a bill that addresses this--albeit indirectly. A.B. 2363 set out to adjust this 85th percentile rule, but it got so much opposition from (checks notes) the CHP, AAA Auto Club, and the Teamsters, that in the end it was reduced to calling for a task force to study the issue.

That task force was required to meet "on or before" July 1, 2019, which is today! It met that deadline, holding its first meeting last week.

The Zero Traffic Fatalities Task Force force is huge--25 people were invited to participate--and it has a lot to do in a short time. It will meet a total of four times, and has until January to produce a report, as required by A.B. 2363. The task force is also supposed to "develop a structured, coordinated process for early engagement of all parties to develop policies to reduce traffic fatalities to zero."

The task force is specifically required to discuss: the existing process for establishing speed limits, policies for reducing speeds, engineering recommendations on increasing safety and speed, and how bike and pedestrian plans affect the current 85th percentile method. It is also supposed to make "a recommendation as to whether an alternative to the use of the 85th percentile... should be considered, and if so, what alternatives should be looked at."

So many engineers have been using the 85th percentile method to set speeds for so many years that it is hard for them to fathom why or how it would be changed--hence the mealy-mouthed phrasing of that last task. For some, there is no doubt that allowing drivers to determine "reasonable speeds" is a bad way to go about keeping Californians safe. Others cling to the standard engineer-speak because, as the manual claims, "Speed limits that are set near the 85th percentile speed of free flowing traffic are safer and produce less variance in vehicle speeds."

A.B. 2363 called for some specific organizations to participate in the Task Force, including the CHP, researchers from UC Berkeley's SafeTREC, Caltrans, and the Department of Public Health. There are also representatives from local governments, and bike and walk advocates. Also AAA Auto Club, the Teamsters, and the Electronic Frontier Foundation. And at least one person whose presence is a real head-scratcher: Jay Beeber, who misleadingly calls himself "Safe Streets L.A." while campaigning against road diets and bus improvements.

The meetings are not open to the public, and their discussions are not available for listening in on. Several attendees Streetsblog spoke to mentioned that the first day-long meeting was mostly introductory, with a general discussion to define the issues and begin recommending solutions.

Cyclist Meghan Sahli-Wells, Culver City mayor and representative of the Southern California Association of Governments, said the first meeting was "a good start in getting to know the key concepts about current traffic engineering, the 85th percentile rule, and the unconscionable amount of traffic fatalities we experience under this system."

"We got a copy of the 2014 California Manual for Setting Speed Limits [PDF], which describes this approach," she wrote in an email. "When I read [the passage about speed limit setting relying on driver behavior], my blood boils, because it is so deeply flawed, with deadly results," she wrote.

On the other hand, the manual does make a few reasonable points. For example, "the setting of speed limits requires a rational and defensible procedure to maintain the confidence of the public and legal systems" are wise words--although perhaps not supported by the 85th percentile method.

And this: "Regardless of the posted speed limit, the majority of drivers will continue to drive at speeds at which they feel comfortable. The question then arises, 'Why do we even need to post speed limit signs?'" This is hard to argue with, in the face of a lack of enforcement and the current illegality of automated enforcement in California--which is why design is so important. For too many years streets have been designed for more cars to drive faster--see Balboa Blvd, again, as one of many examples. That street is a traffic sewer and yet many people live on it and even more try to navigate through and across it. No wonder so few people walk and bike there.

The manual also points out that other factors affect driver speed, perhaps more than whatever speed limit is set, including the design and physical characteristics of the roadway, the vehicle, the driver, what the traffic is like, weather and visibility, and--last, perhaps least?--other users on the road, like people walking, waiting for transit, riding a bike, trying to cross the street, etc.

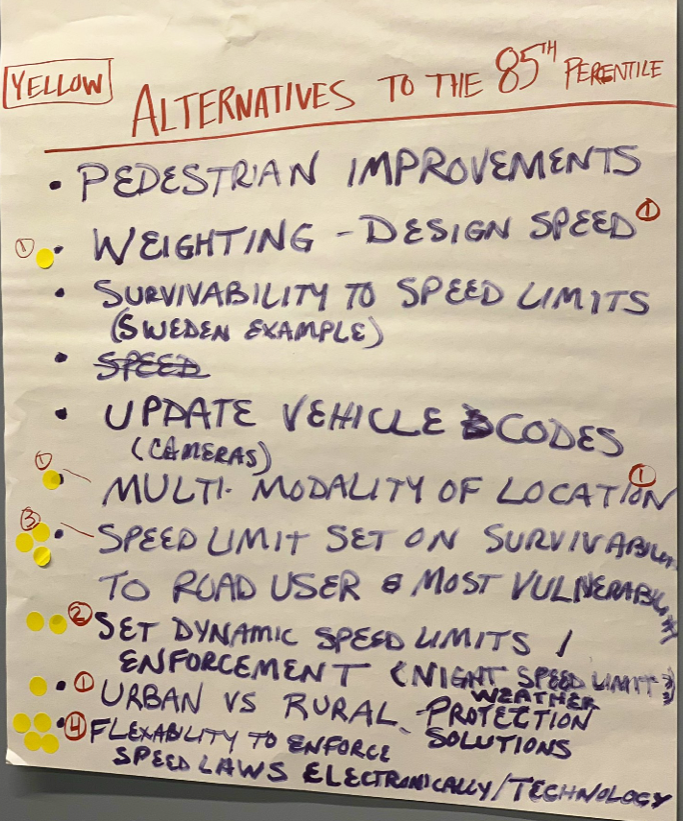

A brainstorming white board tweeted out by Sahli-Wells gives a hint at some of the ideas being discussed, but with one meeting down and three to go, it's hard to know what direction the conversation will take. The Zero Traffic Fatalities Task Force includes fierce advocates for the safety of all road users, but it also includes participants who are more concerned with freedom from speeding tickets, economics, and privacy than they are with safety.

Stay tuned.

Follow Streetsblog California on Twitter @StreetsblogCal