Among the recent allocations of transportation funds from the gas tax, S.B. 1, was money for a pilot project to integrate transit services in California. Three regional transit agencies—Capitol Corridor, San Joaquin Regional Transit District, and Los Angeles-San Diego-San Luis Obispo Rail Corridor Agency (LOSSAN)—will team up with seven as-yet-undecided connecting transit agencies to work on creating a “seamless” experience for transit riders.

The pilot program was included within an $80 million grant made to the Capitol Corridor Joint Powers Authority, which is the responsible agency on the pilot program. In total, $27 million will be available to fund the five-year pilot that can offer lessons and practices that can be expanded to the rest of the state.

The notion of a “seamless” transit trip—wherein a transit rider can effortlessly travel across regional boundaries among different transit agencies and using various modes—is a vision that has long eluded California. But it is becoming a reality in other places, with various levels of success, and there's no reason it can't happen here.

At least, there is no technological reason it can't happen. That was a big take-away from the California Integrated Travel Conference convened by the California State Transportation Agency (CalSTA) this week, which set out to jump start the pilot. The technology exists to make riding transit as simple and easy as driving a car—or maybe easier—and it is being used in Europe and elsewhere.

Another take-away was that, in places that have been finding ways to integrate ticketing or scheduling—or just make it easier to figure out and ride transit—ridership has increased, bucking the U.S. trend of declining numbers of transit riders. And in some cases agencies have been able to increase revenue as well.

Most of these changes have happened in the last five to ten years, in Hong Kong, Sweden, Norway, and London, among others.

Riders already know what is wrong with transit in California. Anyone who has tried to plan a regional point-to-point trip, even with the increasing usefulness of trip planners like Google Maps, has had the experience of throwing up their hands in defeat. It always looks easier—and faster and cheaper—to take a car. But that's not necessarily the case—and it doesn't have to look that way.

At the conference, representatives from Transport for London, Norway, and Sweden talked about their transit systems' increasingly sophisticated use of ticketless transit payment systems and coordinated schedules. The message was that those systems faced many difficult obstacles, but with commitment found a way around them, and are succeeding—and that California can do the same.

California's challenges are many. The state has hundreds of transit agencies but there is no overseeing agency that sets rules. Even Caltrans, which is responsible for doling out federal and state transit moneys, has only recently formulated a Statewide Transit Strategic Plan, and even then the state has struggled to figure out its role vis-a-vis transit.

Public transit in California also has a mandate to serve everyone, unlike private companies that can pick and choose, and market to, specific customers. That brings other challenges that not every place has had to face—in Sweden, for example, smart phones are ubiquitous, so payment systems using smart phones are useful to most riders. In California, however, transit agencies have to be able to serve people who don't have phones, credit cards, or bank accounts.

These are not insurmountable difficulties. As presenters repeated, these are simply technological questions. And coming up with a solution to them should be “agnostic” anyway, as pointed out by Jonathan Donovan of Masabi, a private company that develops transit apps. “We don't even know what platform people will be using five or ten years from now.”

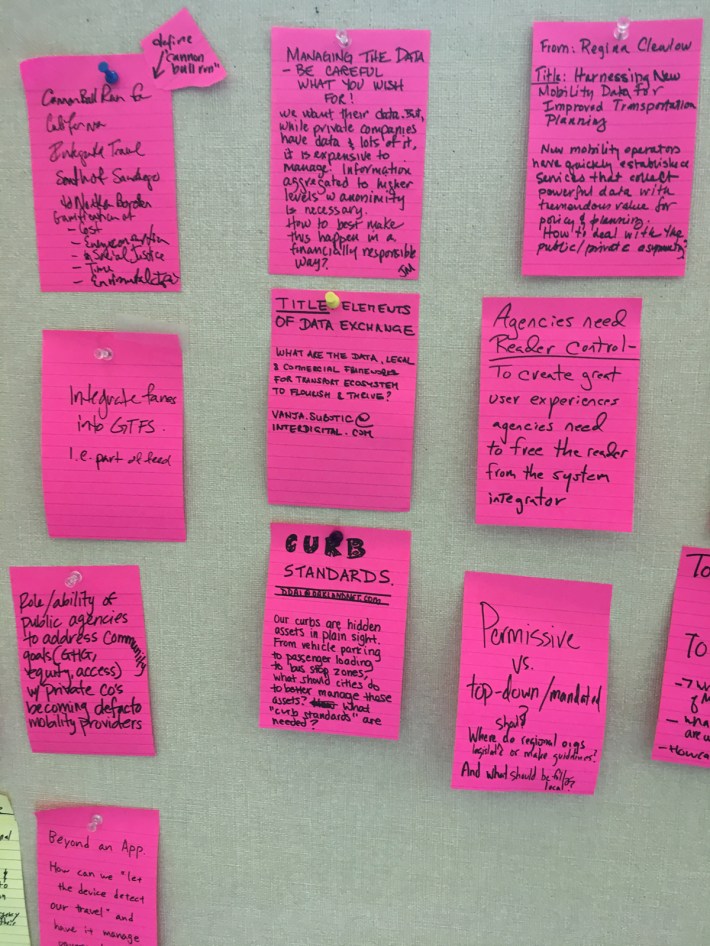

A big question at the conference was about the role of the state. Should it just pass out funding? Should it have a governing role, or a guiding role? Should it function as an information clearinghouse, or should it handle data and create specific information standards for sharing among agencies?

The question was not answered, because figuring it out will be one of the functions of the forthcoming pilot program. Whether the five-year pilot is successful, and even if not—a mantra at the conference was “fail fast” so as to learn quickly from mistakes—what lessons it learns will be useful and expandable to other agencies and groups of agencies throughout the state.

“This is a dialogue,” said Chad Edison of CalSTA, who is helping lead the effort. “There are many different directions the project can go. It could be about fare integration, or service integration, or data sharing, or all of that. The question for us is, what can be addressed now?”

The pressure is immense. Ridership is dropping, congestion is increasing, and while California is investing more money in transit—hurray!—it is also investing in making it easier and faster to get around by private car.

Transit agencies know they need to change, and that it won't be easy. Jennifer Bergener of LOSSAN described a “tribal” mindset among transit agencies that slows down collaboration. Carsten Puls of DB Engineering, who has worked on German transit systems and on California High Speed Rail, commented on the “greatly increased ridership” that came with fare and service integration in Germany. “It's about a mindset,” he said. “Transit agencies have to understand that integration is not going to cannibalize their services—instead it will help them grow.”

Jesse Waas of TriMet in Portland offered an interesting example of how objections can be overcome. That agency created a fare system somewhat similar to one in London that automatically chooses the least expensive fare, adjusting it as riders use the system throughout the day. The result has been that riders don't have to spend any time figuring out whether to invest in a day pass, a weekly pass, or a single fare—making the decision process moot.

The result has also been increased ridership. While an agency might believe that offering every rider the cheapest fare possible would cost them money, the fact is that they end up making more money simply because the entire process is less irritating to riders.

“Customers do not want to be confronted with the complexity of transit systems,” said Waas, “and we have the technology to isolate them from it.” Uber and Lyft have been highly successful in part because they recognize—and have been able to capitalize on—the importance of convenience.

CalSTA's Edison said that while there is definitely a need to develop common standards and consistency among agencies, “this is not about getting rid of competition—it's about opening up possibilities and offering help.”

What form all this will take in California will become more clear as the pilot program takes shape.

“This is an opportunity for California to learn from other systems,” said Edison, “and to leapfrog to the state of the art.”

Many of the transit systems that have successfully adopted better integrated systems went through a process of evolution to get there, he added. “We expect an evolution throughout the state as well.”