The last words Amy Cohen ever heard her son Sammy say were "I love you mommy."

She had kissed him goodbye that morning as he headed out to walk to his middle school, four blocks down from their house in Park Slope, Brooklyn.

Later in the day, she got a call: Sammy had been hit by a driver. He died a few hours later. She was blindsided.

"I really never imagined that this could happen," Cohen said. "I don’t think anybody can even put it into words. You never recover."

Every day, more than 100 people are killed in traffic crashes on American streets. Their families receive that unimaginable phone call. And for the people who endure this trauma, there's remarkably little in the way of institutional support. They read headlines in the papers blaming the loved one they lost, and they try to soldier on, often alone with their grief.

But that is starting to change, as victims' families and crash survivors connect with each other and set out to prevent other people from feeling the pain they've gone through.

After Sammy was struck, Cohen decided she couldn't stand idly by and while other people got injured and killed in traffic crashes.

Days later, she was testifying for traffic safety measures in New York. At the time, the city was trying to reduce its default speed limit from 30 to 25 mph and needed votes in the state legislature to make it happen.

Through that advocacy, Cohen met other people who had lost children, spouses, brothers, and sisters. Though they crossed each other's paths, they weren't organized as a distinct and coherent group.

"My background is as a social worker," Cohen told Streetsblog. "I said, 'I can’t believe I’m doing this by myself.'"

With help from Transportation Alternatives, Cohen and a small group of other New Yorkers who'd lost loved ones in traffic crashes founded Families for Safe Streets. It was the first group of its kind in the country, devoted specifically to supporting people in grief due to traffic violence, and to advocating for policies that prevent collisions, injuries, and the further loss of life.

The organization launched in January of 2014, a few months after Sammy's death.

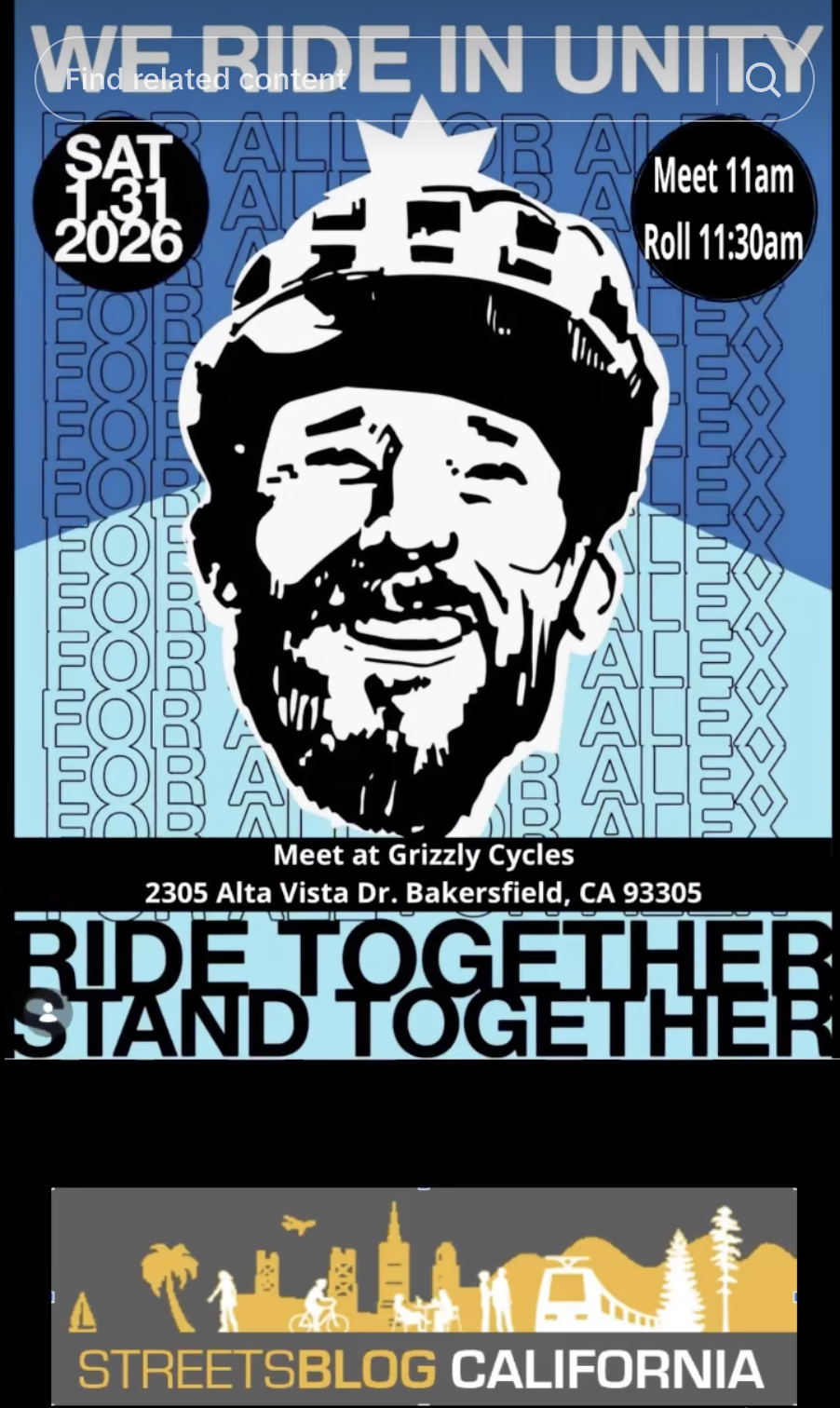

And in the past four years, Families for Safe Streets New York has helped launch chapters in Oregon, New Jersey, Austin, Southern California, San Francisco, and Alexandria, Virginia. A few more chapters are in the works, says Cohen. Streetsblog will be profiling members of these chapters in a series of articles about this emerging movement.

Today, the New York chapter of Families for Safe Streets has about 200 members. All of them have lost a loved one to traffic violence in New York City.

FSS operates by the social work principle "meet people where they're at." Modeled to some extent after Mothers Against Drunk Driving and Everytown for Gun Safety, FSS offers peer support groups and one-on-one mentoring.

"You get incredible support knowing that you haven’t been singled out by the universe for this horrific tragedy," said Cohen. "There was literally a member of the group that I would say saved my life. She was there in a way for me that we tried to formally replicate."

FSS also offers advice on what can feel like overwhelming tasks following a death or serious injury: getting an attorney, filing an insurance claim, and gathering evidence to support a legal case.

What the group is best known for is advocating for public policy changes. Families for Safe Streets encourages people who have endured a tragedy to "push back."

Just before Sammy's death, Cohen, her husband Gary Eckstein, their daughter Tamar and Sammy took a trip to London, where there were signs everywhere telling drivers not to go faster than 20 miles per hour.

"I said to my husband, 'If we had [this] in New York city, Sammy would still be alive.'"

Cohen and other bereaved families testified before state lawmakers in the campaign to lower New York's default speed limit from 30 to 25 mph.

In New York, the general rule with new state legislation is, "It never happens in the first year," said Cohen. But the members of Families for Safe Streets conveyed an urgency that lawmakers hadn't been exposed to before. The bill passed the same legislative session.

"We can cut through some of that red tape," said Cohen. "We give them moral authority."

Members of FSS also appear at public meetings where street designs are reviewed. In New York, the city often defers final decisions to community boards -- groups of appointees who are supposed to represent the neighborhood, but often consist of a much higher share of car owners than the general population.

"We still live in a driving culture," Cohen said. "We don’t change everyone’s mind, but we do change many more minds than I think advocates were able to do before we came along."

The next campaign for FSS is expanding automated speeding enforcement in New York City. Again, it will require state approval. Right now state law caps the number of speed cameras in New York to 140 school zones -- for a city with 6,000 miles of streets and more than 2,000 schools. Legislation endorsed by the Assembly, but not yet the State Senate, would double the number of speed cameras and loosen restrictions on where and when they operate.

To support the legislation, Families for Safe Streets built a coalition of 300 supporting groups, including unions, hospitals, schools, and most of the City Council. The campaign is mobilizing this spring to get the bill passed in time for the next school year.

Becoming an advocate won't be the right choice for every family affected by traffic violence. "It’s not an easy road," Cohen said.

She still tears up when she thinks about Sammy and what happened to him. But through her involvement with Families for Safe Streets, Cohen says she's found a meaningful way to channel the anger and pain to help overcome a "public health crisis that goes unacknowledged."

If you would like information about starting your own Families for Safe Streets chapter, you can call 844-FSS-PEER/844-377-7337 or email info@familiesforsafestreets.org.