Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

The Greenlining Institute, an Oakland-based nonprofit, released a report today describing a three-step framework that can be used to help communities figure out which transportation investments best serve their needs.

The Mobility Equity Framework outlines a three-step process that involves, first, bringing a community together to identify its mobility needs; then conducting an equity analysis to identify the transportation modes that bring the most benefits and minimize burdens; and, last, having the community itself make the final decisions about which modes to invest in, preferably via democratic vote.

The report's authors focus on the creation of a tool to help people work through the second step: thoroughly analyzing the benefits and drawbacks of transportation investments. The focus is not on solving a single problem or even two, but on exploring and comparing all the benefits and drawbacks of potential investments to allow the community to make an informed decision on how to provide for their needs as identified in the first step of the process.

This is not just a pie-in-the-sky idea. “There is no need to reinvent the wheel,” said Hana Creger, Environmental Equity Coordinator for Greenlining and one of the authors of the report. “There are existing methods that encapsulate the goals of our framework.”

She gave the example of “participatory budgeting,” which she said is “not a radical, untested idea.” Participatory budgeting, which aims to create a democratic process for deciding how to spend public money, has been used in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Oakland, and the city of Vallejo is conducting the first citywide participatory budgeting process.

The key, said Creger, is that a “community should decide what their needs are and THEN figure out the transportation options.” The Mobility Equity Framework, she said, “should be prioritized in low-income areas where community needs have been marginalized for decades.” But the method can be applied in any community.

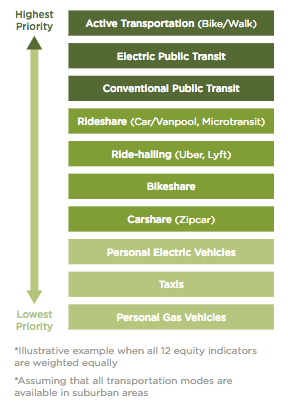

Transportation investment decisions are usually made in a political context that involves trade-offs between major players who garner support by offering a little bit of something for everybody. A thorough analysis of which investments bring the most benefits, including economic and environmental ones, is not the way transportation planning usually works, and the result, says the report, is that “too often, walking, biking, and public transit are afterthoughts in transportation planning and investments.”

Clean transportation options offer benefits that may not show up in a basic cost-benefit analysis conducted without input from community members. Not only can they reduce health and safety impacts and costs, but they can bring job benefits, reduce income inequality, and greatly increase access to services.

But people need to be able to see and understand the advantages and disadvantages of all transportation modes. “This is particularly important in low-income communities of color,” says the report, “because many physical, logistical, financial, technological, and cultural barriers may reduce access to shared mobility” such as that available with bike-share, car-share, and ride-hailing services.

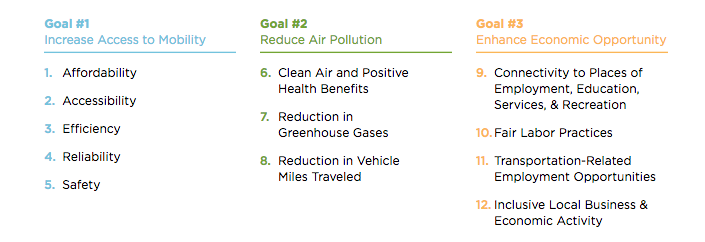

The framework provides three overarching equity goals: to increase access to mobility, to reduce air pollution, and to enhance economic opportunity. For each of those goals, the report provides a list of “equity indicators” that can be measured and applied to potential investments. For example, under the first goal of increasing access to mobility, transportation modes can be analyzed according to affordability (How much do households spend on transportation?); accessibility (Do services connect homes, jobs, and other destinations? Do people need smartphones or credit cards to use them? Can disabled people use them?); efficiency (How frequent are services, and how long is travel time?); reliability; and safety (collision risk as well as personal safety from harassment or profiling).

It's important that all three steps of the process be completed for the best outcomes, the report emphasizes. And the outcomes will vary with each community. “While some communities may prefer to compare the equity outcomes of all modes, others may only focus on those most relevant to their needs,” says the report, depending on, for example, residential demographics or the most common trip type.

While each community may end up making different decisions, having a complete analysis of benefits and drawbacks will likely change local outcomes. “For way too many years, the needs of cars have been prioritized over people,” said Creger. “This is one of the reasons The Greenlining Institute, which has been advocating for racial and economic justice for 25 years, got involved in transportation advocacy—because of a lack of healthy commute options. Commute time is the biggest indicator of economic opportunities. But our public transit systems are inadequate and insufficient for low-income folks, and our cities are choked with traffic and pollution from cars.”

“This is not just an inconvenience, either. There are also major health impacts for people living in these communities.”

She offered as an example of how the process might work for a discussion of solutions for traveling across the San Francisco Bay. Proposals have been floated for years to study adding another crossing, which some say should be a bridge to allow drivers to get around traffic on the Oakland Bay Bridge. But, said Creger, under the equity framework, the first question would be about the needs of the community most impacted by a new bridge. Using the framework and its tools for analysis, a solution that involves a second BART tube could be found to provide just as many regional benefits in terms of congestion relief without destroying any community in the path of a bridge.

The authors see their framework as benefiting low-income communities of color that have been left out of transportation decisions for years, and who bear the brunt of negative impacts from the decision that have been made. While local decision-making processes can adopt the framework, they will need support from state and regional entities like the California Transportation Commission—a decision-making body not exactly known for its democratic approach.

Caltrans recently provided a grant to the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the Bay Area's transportation decision-making body, to conduct a pilot participatory budgeting process.

Creger said that a pot of funding about which to make decisions is a first step. “The more funding that can be allocated for these community-involved decision making processes, the more they can build capacity,” she said. Completing the entire three-step process, including the final democratic vote, ensures that the community is the source of funding decisions that affect them. “Participatory budgeting not only increases voter participation, it helps to build trust between communities and local government,” said Creger. “That includes engagement with youth, with immigrants, and with incarcerated people”--the entire community.

“We definitely want to ensure that there is an educational component throughout the process,” she said. “Not just on how transportation planning works, but what options there are, how they work, how to use them—the basic landscape of what’s out there. Also what are the cost savings and health benefits of each.”

“How you make transportation work for people is by listening to their ideas and allowing them to make decisions,” she added, “and in no place is that more important than in low-income communities of color that have traditionally been shut out from such forms of engagement.”