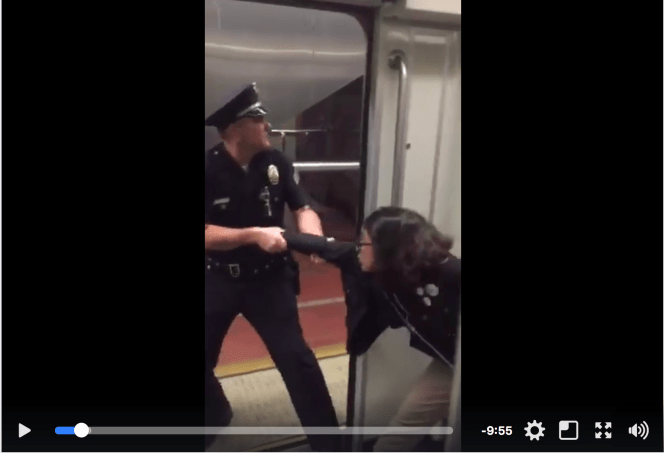

Back in January, I posted the story of 18-year-old Bethany Nava being dragged off a train for ignoring requests to take the foot she had curled underneath her off the seat. In it, I raised questions about whether this was the best we could ask of law enforcement and did a bit of a dive into how and why not everyone feels reassured by the more intense police presence on Metro transit.

“Burn the witch!” came the booming reply across several social media platforms.

I was officially shooketh.

Not because I think it's OK for people to put their feet all over seats and ignore multiple polite requests that they comply with Metro's code of conduct. [Spoiler alert: I'm not a fan. So, if you’re looking to read me on how rude teens and/or feet on seats are the beginning of the end of civilization as we know it, put a pin in it. For all our sakes.]

But because I genuinely struggled to understand how people had come to the conclusion that a stubborn teen being dragged off a train and taken away by enough officers to field a baseball team was a) proportionate to the crime, b) the best we could expect from law enforcement, c) what we should expect from law enforcement, and d) an outcome that makes transit feel safer and more welcoming for all.

People love seeing others get their comeuppance - that much is clear. And rude behavior on transit understandably strikes a deep chord in hearts across the city - including, and perhaps especially, among many of those who themselves would never deign to set foot on a bus or a train.

But people had been so caught up in detailing the crimes against humanity her “poopy feet” (as some referred to them) had wrought that there was very little space for reflection on the larger implications of what it was that they were cheering.

Even Metro struggled to carve out space for reflection on the incident. The first statement issued by Metro CEO Phil Washington on January 24 regarding events seemed to indicate that he, too, was troubled both by the images and its larger implications. Within hours, however, the outpouring of burn-the-witch sentiment and what we can only presume were multiple phone calls from official agencies equating Washington's disappointment over the images with a lack of support for law enforcement meant his original statement would be excised from The Source. It was quickly replaced with one reiterating Washington's respect for law enforcement and a plea that we not rush to judgment regarding the officer's actions.

As Metro prepares to refine and implement its newly approved equity framework aimed at centering the needs of lower-income riders of color in the agency's policy and planning processes, it needs to find the courage to revisit the incident and its implications.

Because while the staff report mentions the need to improve transit access for lower-income riders of color and guard against displacement and gentrification that would hinder their access, there is no explicit attention given to ensuring that approaches to the policing of the system do not constitute a barrier to access for those same riders.

The details of framework will surely be filled in as the engagement process gets underway. But the absence of explicit mention of the need for engagement around approaches to policing and accountability is surprising in light of the prioritization of policing (the visibility of law enforcement has doubled since last July), the role Metro believes perceptions of “safety” play in attracting greater ridership, the complexity of the issue, and the fact that transparency around how the system is being policed remains a problem.

The best way to connect the dots between the incident involving Nava and Metro’s approach to equity might be via the most common response I saw any time anyone questioned how the encounter between the teen and the officer played out: “She disobeyed him, what else was he supposed to do?”

What else, indeed.

It is a troubling question. For one, it implies that once a person being engaged is deemed noncompliant, all bets should be off the table.

To that end, a startling number of commenters suggested the officer was too restrained and not rough enough, either with her or the bystanders. Others wanted to see her and those questioning and/or insulting the officer locked up. Inglewood Mayor and Metro Boardmember James Butts, in some pointed remarks at the January 25th board meeting, took it a step further, expressing surprise that the officer hadn’t moved to “smack” some of the people around him as he radioed for help with the “brat.” [Discussion of the incident begins at 24:00; Butts’ remarks begin at 26:03]

Given the abuses of the use of force we’ve all been witness to over the past several years and the fact that “failure to comply” has been used as a pretense to demean, cuff, frisk, ticket, arrest, tackle, or shoot men and youth of color - many of whom had neither posed a threat nor committed a crime - that line of reasoning is deeply worrisome.

But the question also points to the central dilemma created by the deployment of armed law enforcement officers to police etiquette and other civil infractions. Namely, that engagements that begin as an effort to exact compliance, over the course of the encounter, can instead become about the exertion of control.

In this case, the teen’s noncompliance with the rules appeared to be clear [she says otherwise, arguing her foot was resting on her own leg, which is why she responded to the officer with questions rather than “compliance”]. As the situation escalated, however, it became less and less clear what kind of compliance the officer was hoping to exact and more and more evident that his primary goal was establishing control over her, the situation, and the people around him.

In an effort to offer unequivocal support of the officer’s actions, Butts - who has overseen three police departments - explained why this was. In the process, he inadvertently made a surprisingly strong case for rethinking the deployment of armed officers on transit.

The teen, he said, had put the sergeant in an “impossible” situation.

Once she did not comply, Butts continued, the officer had only two choices: leave her alone and show the crowded train car that anyone could do whatever they wanted on transit or call ahead and get officers to meet him at the next station.

The officer, as we all saw in the recording, did neither. But Butts explained that the reason was because the officer “would have [had] no expectation” of resistance.

In framing it in this unusual way - that it was wholly unexpected that an officer specifically tasked with engaging people who were not complying with rules might ever be met with noncompliance - Butts was not only absolving officers of having to have any capacity for de-escalation, he was also arguing that the teen had put the sergeant in significant danger.

A lone officer with a gun on his hip in a crowded train car was now at risk of having his weapon snatched from his holster as he tried to remove the girl from the train, Butts explained.

As such, an officer has no choice but to see everything as threatening: the teen hanging onto the pole because she didn’t want to be dragged off without her belongings, the girl’s backpack (which Butts says shouldn’t have been given back to her uninspected), the people filming on the platform on the side of his service weapon, and Selena Lechuga, the woman who questioned, insulted, and, after being cuffed and led away, spit at the officer.

The officer would have been within his rights to yell and curse at them all to step back, Butts suggested.

“He cannot afford to lose in a confrontation,” Butts reiterated. “He has a firearm.”

On this last point, Butts is not necessarily wrong: for the safety of the officer and bystanders alike, an armed officer cannot afford to put him or herself in a position where their weapon could be seized or a weapon could be pulled on them. And the need to protect against those kinds of outcomes is often why officers behave in ways that sometimes appear counterintuitive or overexaggerated to the public.

But if that is the case, as Metro Boardmembers Hilda Solis and Jackie Dupont-Walker pointed out during their comments, then why was the officer alone (making him more vulnerable)? Why wasn’t a citation given or other options explored before hands were put on the teen? Knowing that an armed officer alone faces such a dilemma every time they engage a member of the public, every possible precaution should be taken to ensure an officer never finds him or herself in a situation where they feel threatened.

Because as Butts himself had said, once the sergeant put hands on the teen, there was no backing down: “He had to have a resolution.”

And, as we all saw, that “resolution” was a teen and an angry bystander being hauled away in cuffs by enough officers to halt a bank robbery and eventually cited for things that had nothing to do with feet on seats.

For many within Metro’s core ridership (Lechuga included), Nava being dragged off the train evokes images of the way their communities have historically been and continue to be disproportionately profiled and mistreated by law enforcement.

And that’s a problem.

Not because of what this officer did, per se, but because of the discretion it suggests officers have to decide which codes will be enforced and how. Because of the fear that that discretion will be used to target youth and men of color as a way to let them know they are being watched, to make them feel less welcome, and to run warrant checks. Because of the fear that those from disenfranchised communities who have endured significant struggle could easily have their forward momentum derailed. Because they already feel criminalized in their own neighborhoods, where they are regularly stopped and frisked. And because of the fear that an encounter over a similarly minor infraction - real or perceived - could end up escalating to something much more serious.

That last fear was realized just this past summer, when 23-year-old Cesar Rodriguez was crushed by a Blue Line train after being stopped for fare evasion at the Wardlow station.

The details of that August 29 incident as yet remain unclear - the family was first told the death was an accident. Later, they heard that he had tried to jump off the platform to escape officers. The Long Beach Police Department (LBPD) statement on the matter offered a third version of events, stating that after the Transit Security Officers - Metro’s security team tasked with checking fare compliance and issuing citations - alerted the LBPD, Rodriguez was detained on the platform for fare evasion. Officers then searched him and found he had narcotics, apparently prompting Rodriguez to try to flee. “Both he and the officer fell onto the platform,” the statement reads. And because “the suspect’s lower extremities were partially off the edge of the platform” as a train was incoming, Rodriguez was struck and trapped between it and the platform.

It’s a horrifying scenario that thankfully has not repeated itself since. But the questions the incident raise - why Rodriguez was searched over a $1.75 non-criminal infraction, how he ended up on the ground, why the family has yet to have any answers, and why such a tragic incident did not prompt more reflection within Metro - are all cause for pause.

We all deserve safety and security and, yes, fewer feet on seats as we try to get where we are going. And law enforcement can play a part in that.

But fulfilling that mandate means recognizing that where some riders might feel reassured to see armed officers on board a train, others might feel unsettled or, as some have expressed to me, like they are living in an oppressive police state.

It also means recognizing that because of law enforcement's history of repression in the neighborhoods where Metro's core ridership resides, there is both a greater potential for more antagonistic encounters between officers and members of those communities and a greater likelihood that members of those communities will be perceived as posing a threat.

And as boardmember Butts' own testimony implied, the fact that officers are armed makes it all the more likely that "threats" will be seen to be lurking everywhere and that officers will be all the more inclined to respond accordingly.

In the lead-up to last year's approval of the policing contract between Metro, the LAPD, the Sheriff's Department, and the Long Beach Police Department, there was very little in the way of meaningful engagement around what safety and security for all meant in practice.

Since then, it appears that most of Metro's public engagement on this issue has been with Labor/Community Strategy Center (LCSC) - the group that has filed civil rights complaints and lawsuits against Metro and that has demanded that law enforcement be removed from transit altogether. While the LCSC represents an important voice, they're hardly the only one Metro needs to be engaging.

The approval of a new equity framework affords Metro an important opportunity to revisit the question of what it means to make riders of all stripes feel welcome on transit and to establish a new process to allow for innovation, trust-building, and accountability around safety as the system grows.

Not just because the enforcement of code of conduct violations should not end in scrums. But because all the good work put into centering the needs of lower-income riders of color will be for naught if the presence of law enforcement discourages them from riding.