Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

Now that Senate Bill 1 has taken effect, and gas taxes have increased by twelve cents, the battle for the hearts and minds of Californians has begun in earnest.

Depending to whom you listen, S.B. 1 is either a boondoggle to line the pockets of politicians, or the beginning of a new, pothole-free era for California roads.

Anti-tax crusaders are sharpening their swords in anticipation of a repeal campaign, but meanwhile the price of gas bumped up a bit and some of that revenue is starting to hit the streets.

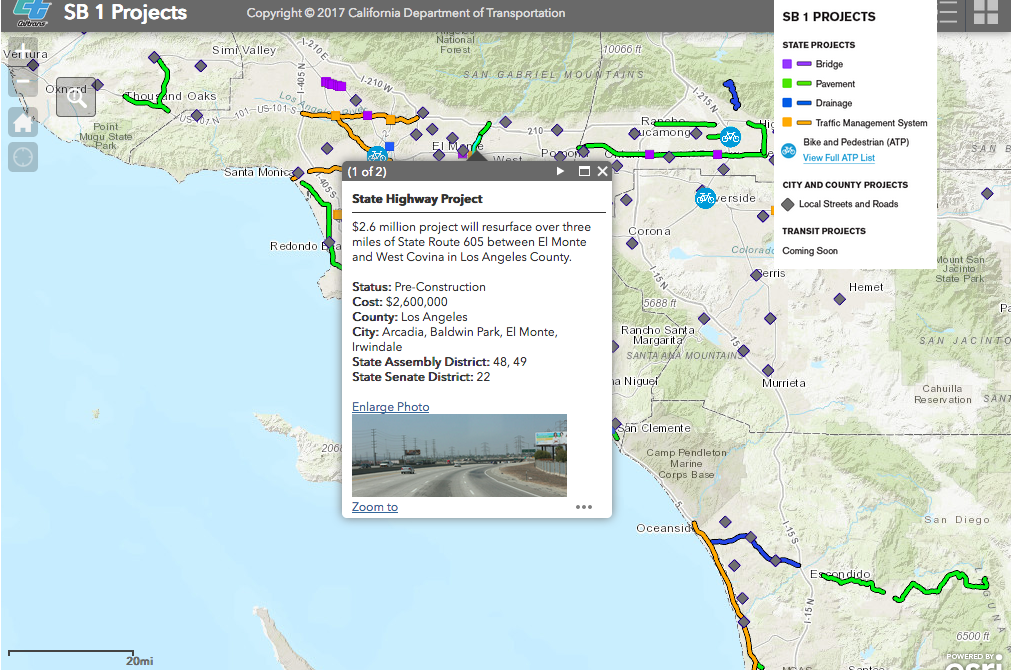

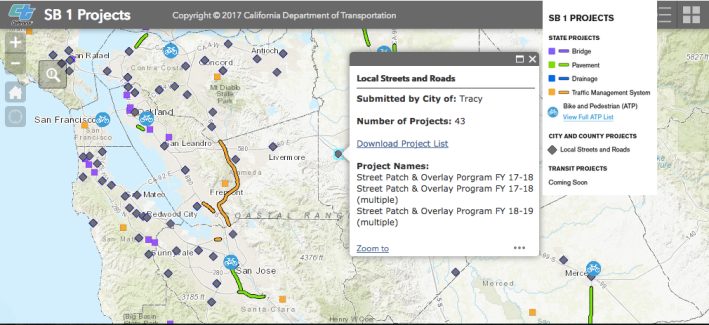

Caltrans, which will be managing much, but not all, of the new revenue from S.B. 1, has been working to let people know where that money is going. Expect many “your tax dollars at work” signs popping up as the various programs start work in the coming year or so. Meanwhile Caltrans has created an interactive map showing what the gas tax revenues are being spent on and where. It's new, and so is the tax, but there are already a lot of projects mapped out.

They include active transportation projects, road and pavement repair, and upgrades throughout the state. For example, $26 billion will be spent over the next ten years on deferred maintenance and repairs on local streets and roads, matching funds for projects in local sales tax measures, and planning grants. That money is allocated by formula based on population, and each local jurisdiction decides what to spend it on.

Transit projects are not yet on the map. S.B. 1 will contribute an estimated $1.4 billion over ten years to the Transit and Intercity Rail Capital Program, and the guidelines for allocating that money are still being worked on.

Meanwhile Caltrans also just released its draft Asset Management Plan, which is basically an outline for how it plans to keep state-owned roads, bridges, and traffic management systems in a state of good repair. That plan shows a stark difference between what it can do with S.B. 1 and what it can't do if S.B. 1 were to be repealed.

Other agencies and supporters are holding press events to highlight the benefits of the gas tax, among them AC Transit, which says: “SB1 funds will give AC Transit the ability to purchase new buses and replace old ones, putting these dollars to valuable use right here in the East Bay because half of our current fleet is manufactured . . . in Livermore. Thanks to SB1, about $7 million dollars are anticipated to come directly to AC Transit in operating funds that keep our buses moving – particularly on bus lines where no other public transit is available.”

Meanwhile Republicans have floated two initiatives to repeal S.B. 1, which could go before voters a year from now. One is a simple repeal, but the other one, proposed by former San Diego City Councilman Carl DeMaio and Republican gubernatorial candidate John Cox, would add a requirement for voter approval of any gas tax increases.

Given how difficult it was to come to an agreement on S.B. 1, that could effectively end any attempts to raise revenue to pay for rising transportation costs in California.

Meanwhile the campaign for the repeal effort is already turning ugly, attacking individual legislators who voted for the increase, including Senator Josh Newman of Fullerton, who is facing a recall effort over his vote.

It's so tempting to dismiss the repeal efforts as coming from outnumbered anti-tax idealogues who don't understand transportation finance in California. But that would be a mistake. They can get plenty of mileage out of appealing to consumer's wishes for free things, although the modest bump in gas prices is unlikely to help them much on that. While some local news shows and op-ed columns have been frothing about the “spike” in gas taxes, twelve cents a gallon is not much in the context of the fluctuating gas prices—related to refinery problems and industry manipulations, not taxes—that are a frequent occurrence in California.

A brief history: gas tax revenue has been declining for a long time, in part because of more efficient vehicles and more driving (leading to more maintenance needs), while costs—materials, labor—have been rising. Meanwhile, transportation finance is structured so that it's easier to get funding for new roads than maintain the ones we already have—and that includes local sales tax measures as well as state and federal dollars. So California has continued spending its shrinking amount of transportation funding on new roads, leaving maintenance for both old and new roads for some future generation to worry about.

At the same time, there has been such strong resistance to raising the gas tax that the legislature was reduced to coming up with tricks to get around rules, like one that prevented using gas taxes to pay for interest on bonds that paid for new roads. The “gas tax swap” that ended with S.B 1 was a mechanism few could explain, but which contributed to accusations of “stealing” transportation money to balance the state budget. That made it harder to argue that the increasingly inadequate gas tax needed to be raised, because it all looked awfully fishy. Here are a few references on the above from UCLA gas tax scholar Martin Wachs [PDF] and colleagues [PDF].

The gas tax increase under S.B. 1 isn't enough money, anyway. It won't be enough money to solve ongoing maintenance needs caused by years of neglect and focusing on shiny new projects. It won't be enough to make transit and other modes viable, common, reasonable alternatives for many to driving alone. And twelve cents a gallon won't convince very many people to lay off the driving even a little bit, which is what California really needs.