Putting on Your "Big Boy Pants" v. Putting Together a Good Project

"Let me take a minute to applaud Mr. Price for this incredible project," First District Councilmember Gil Cedillo said as the Planning and Land-Use Management Committee (PLUM) began deliberations on the fate of the billion-dollar luxury residential and hotel project planned for 1933 S. Broadway in Historic South Central on Tuesday, November 1. "Because this is what real progressive change looks like!" [PLUM audio, agenda can be found here.]

As boos erupted from some in the crowd, Cedillo took aim at the residents who had stepped forward to testify about their fears of being displaced, "This is real! This is not a demand, or a slogan, or a chant," he said dismissively.

"We can complain about" the fact that "this project doesn't...cure cancer," he continued sarcastically, but "five percent affordable [housing] where nothing exists? We're told [this] is somehow a bad thing. I don't see it that way."

By his calculations, he said, The Reef's $15 million contribution to the Affordable Housing Trust Fund (AHTF) would allow the city to extend affordability covenants on as many as 500 existing units at-risk of being converted to market-rate housing. Together with the City Planning Commission's recommendation that there be approximately 26 on-site affordable units, he argued, that "represented a 37 percent affordability on this project" and made Ninth District Councilmember Curren Price someone who, "in [his] brilliance, in [his] leadership, in [his] genius," had managed to "put on his big boy pants."

This "vision of shared prosperity, not shared poverty" that Price had cobbled together, Cedillo concluded, had established a model process by which a developer and the community could work together to ensure "the rising tide will lift all boats."

It was a shameful soliloquy of ignorance from a member of a committee tasked with making at least a minimum effort to assess the extent to which the benefits of a proposed project outweighed its potential harms.

It was also unsurprising.

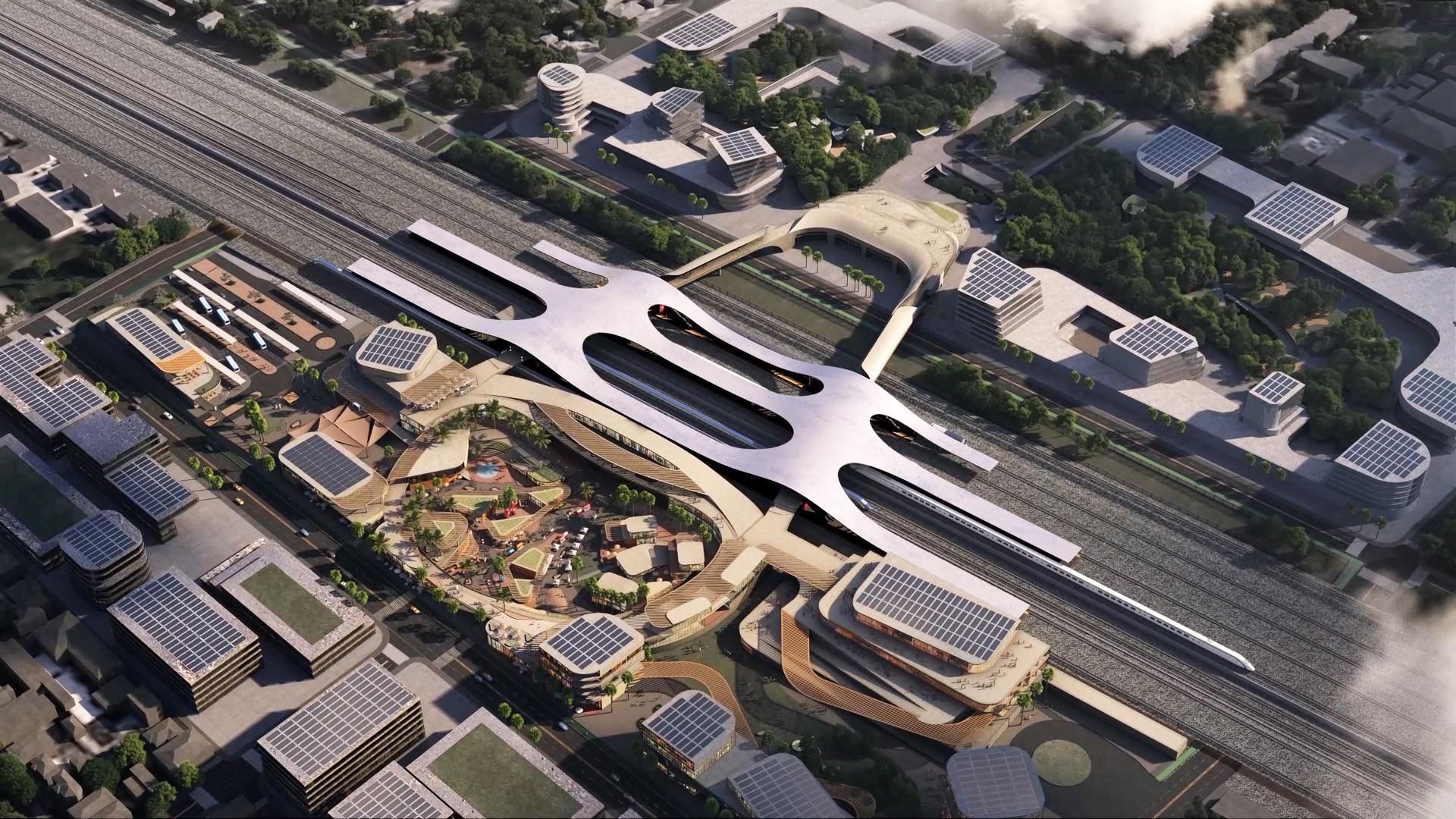

On paper, The Reef sounds like a livability wet dream. The project proposes to transform two surface parking lots near a transit stop into 1,444 units (549 of which would be for rent, including 21 live-work lofts), a 208-room hotel, ground floor restaurants activating the sidewalks, a grocery store, pharmacy, gallery, and fitness center in a community that has so few, a public bike hub (with showers) and improvements to the DASH service, an open plaza with gardens and outdoor performance spaces, and micro-enterprise spaces reserved for small businesses and entrepreneurs from the community. In a town where the housing crunch is so dire that the mayor has prioritized seeing 100,000 units permitted by 2021 and regularly sends out press releases tracking his progress on that front - what's not to love?

Add to all this a Development Agreement (DA) and community benefits package featuring $15 million in contributions to the AHTF, 5 percent on-site affordable units, $3 million to fund health, safety, education, job training, and recreational programming in the community, street trees, a community garden, a local hire agreement, as well as (added in at the PLUM hearing) a community relations ombudsman, quarterly reporting on hiring and procurement to ensure accountability, and the promise the project won't be flipped without permission from the city and payment of all community benefits first.

Then consider that few developers have been willing to take a chance on investing in South Los Angeles. And that even the now-defunct Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) once thought that the best South L.A. might hope for on those lots was a big box store and a surface parking lot, according to Reef attorney (and, conveniently, co-chair of the effort to revise the city's outdated zoning code) Edgar Khalatian of Mayer Brown LLP.

If you knew only these things, you, too, might conclude that the councilmember and The Reef had taken a uniquely community-oriented approach to development.

A deeper probe into the way these agreements came together and the extent to which area residents are actually likely to benefit from these concessions, however, elicits a somewhat different set of conclusions.

The thoroughly cynical way in which both the developers and Price leveraged community benefits to play divisive racial and socio-economic politics, downplayed the magnitude, complexity, and urgency of the housing crisis in Historic South Central, and oversold the extent to which city's affordable housing tools can actually address the needs of those most likely to be impacted by this project is profoundly troubling.

More troubling still is the precedent that such a project sets.

A massive luxury development catering to a well-heeled clientele doesn't constitute a "win" for housing when it is situated on the edge of a neighborhood that is both one of the poorest in the city and the most overcrowded in the entire country. Nor it is a win when the developer's "generosity" is not only an overt bid to avoid having onsite affordable housing but it also leaves a community bitter, divided, and more vulnerable than it was before. It is most certainly not a win when the entire reason such a massive project is viable is because of the extent to which decades of disinvestment and disenfranchisement of the community have depressed land values and stripped the community of political power. And it is absolutely not a win when such a project promises to not only change the character and composition of a historically marginalized community forever, but opens the door for other projects to do the same in similarly distressed communities in the name of revitalization.

With a City Council vote on the project hurriedly scheduled for today (Tuesday) (possibly to exempt the project from any conditions proposition JJJ might impose), it is imperative that the councilmembers fully understand what a vote in favor for this project means for the community and why.

I will try to tell that story here. And I will do my best to make it digestible, but ask you to bear with me because it is long, and it is complicated.

We begin with an examination of the housing crisis within South Central, move on to the evolution of the benefits package, explore the gaps in our affordable housing tools to address the needs of lower-income earners of color, and end by raising questions about whether we can truly build a fair and inclusive city if we continue to sweep the concerns of our most vulnerable residents under the rug.

A Community in Crisis

"To be honest, sometimes, we feel abandoned..." Will Flores, a community engagement coordinator at CD Tech, told the PLUM committee on November 1. "This is an intimidating type of a position [for residents of South Central] to be in."

When a community has endured the kind of neglect that South Central has, it's a lot to ask residents to educate themselves on zoning and other complicated planning concepts, find time to attend meetings, and stand in front of a phalanx of sophisticated city officials who have only a topical understanding of residents' struggles.

"Not everybody is going to [be able to] tell you all the numbers and stuff," Flores said, referring to city planning staff's outright dismissal of concerns that the project would put thousands of residents at varying levels of risk for displacement. "But we’re going to tell you our stories. We’re going to tell you how, when we door knock, we see three families inside of one house. We’re going to tell you how people tell us that [they] are...choosing between the food that they have to eat and paying their rent."

He was speaking both from the heart and from personal experience. As part of the United Neighbors in Defense Against Displacement (UNIDAD) Coalition - a broad coalition of South Central residents and affordable housing advocates that has successfully engaged developers like USC and Geoffrey Palmer in the past - Flores had been active in informing his South Central neighbors about the project, even as he battled chronic health issues that sapped his time, his strength, and his finances. Having observed turnover around USC, downtown, and Echo Park, and tracked changes in so-called "up-and-coming" neighborhoods like Boyle Heights, he was fearful his community would be next. And he seemed wholly unconvinced by The Reef's claims* that, by specifically targeting a wealthy, high-rise-loving set of one- and two-person households, the project would actually avoid gentrifying the area and sparking the indirect displacement of residents. [*See p. 237, response to comment 10-8]

Flores' remarks at PLUM were also a continuation of pleas made at the City Planning Commission (CPC) hearing on August 11, when he had implored commissioners to weigh the larger benefits of the project against the consequences for a vulnerable community. [Audio of the 6-hour CPC hearing can be found here.]

“I am here for my family, my friends, my neighbors, and my community,” he had said then, referring to stakeholders who could not afford to miss work for fear of coming up short on rent or necessities, or losing a job altogether. ”[The developers] say they are bringing jobs and opportunities to our community but they are not taking our realities into account.”

Those realities, he and other speakers suggested, were far harsher than the CPC could possibly begin to understand.

"My reality is me, my friends, my family, my neighbors - we can barely afford to live where we live at now," twenty-year-old Eduardo Bracamontes, a fellow at CD Tech, said of his family. Eighteen-year-old Crystal Aguilar described how every day was a struggle for her mother, herself, and her three sisters to be able to afford a single room with two beds. Nineteen-year-old Ana Torres, a Dreamer of South Central, announced she shared a two-bedroom apartment with nine other people just to be able to make the monthly rent of $1500. Young Cashmere Campbell stated she knew of families that had already had to leave the area because they hadn't been able to keep up with rents. Sophia Kandell of CD Tech testified landlords were already denying residents proper leases in anticipation of The Reef development as a way to make their displacement easier down the line. And it was all happening against a backdrop of a 44 percent jump in homelessness in the Ninth District between 2015 and 2016, Jose Ramirez of St. Francis reminded the commission. Meaning nearly 3500 homeless folks now lived on South Central's streets.

But housing wasn’t the only issue on people’s minds.

“I am a college student,” began Alfredo Gama of the Central Alameda Neighborhood Council, turning the discussion toward policing. “I get stopped by police going out to my car at two a.m. to get my books!"

How much more frequently would he and others like him be harassed once higher-income residents moved in and sought protection from their "suspicious-looking" lower-income neighbors? Such tactics, not uncommon in gentrifying neighborhoods, deepen segregation, make poorer residents of color feel even less welcome in the neighborhood and parks they grew up in, and, ultimately, help fuel displacement.

"They [already] use the police to brutalize us!” Gama protested.

“You guys should really spend the day in South Central and live like low-income families because it’s not easy,” said seventeen-year-old Donna Quintanilla. Being from “somewhere - somewhere there is money,” she continued, meant neither the developers nor commissioners had any idea how all-consuming basic survival could be.

“That’s why you guys find it so easy to come in and change us,” she accused.

Or to dismiss the hard-scrabble efforts people had put in to make their community a safer, stronger, more connected, and healthier place, argued Crystal Gonzalez, who runs a gardening program and a burgeoning South Central growers' network at All Peoples Community Center.

Or to erase the important legacy of black and brown resistance and resilience that had made South Central "the epicenter of hope" for marginalized communities, argued Benjamin Torres, head of CD Tech.

Which is not to say that everyone speaking up at the CPC hearing was against the project. In fact, more than one third of those who stood before the planning commission that August afternoon spoke out in favor of the job opportunities, amenities, and development they felt such a project would bring to South Central.

True - many of those in favor of the project had been bussed in, given Reef t-shirts, and/or would receive benefits as part of the community benefits package. Also true - the uglier comments some of them made served as a reminder of the extent to which both the councilmember and the developers had pitted the community against itself.

But the support for the project also underscored the very real frustration so many in the community - including those opposing the project - have felt at the extent to which their neighborhoods had been denied investment and opportunity for so long. People on both sides of the fence are hungry to see positive change, and they know all too well that rejecting this project may mean it could be years before another comes knocking on South Central's door.

Those opposing the project, however, remained unconvinced that the kind of change The Reef promised would benefit anyone other than homeowners, those with commercial real estate holdings, and developers.

With good reason.

Trickle-down housing is not a viable strategy to promote affordability. Least of all when we're talking about the placement of luxury housing in a deeply economically distressed community. And there are few, if any, examples where the arrival of major developments - luxury or otherwise - have worked out all that well for the lower-income renters or small business owners of historically marginalized communities of color. Instead, those residents know that a project like The Reef is able to get the entitlements needed to be profitable precisely because of the extent to which their community has been devalued over time. They also know that, should such a development successfully anchor the transformation of the area, the existing residents will be seen as the unhappy holdover from the past to be pushed aside, not the foundation upon which to build the future.

All of which explains the genuine fear Flores and so many voiced at the hearings, in petitions, and at protests over the last several months.

A handful of on-site affordable units (as recommended by the CPC) and a contribution of $15 million to the AHTF wouldn't even begin to scratch the surface of the need that could be triggered by the transformation of the community.

If families currently doubling- and tripling-up in unhealthy and substandard housing could barely make rent in the country's most overcrowded neighborhood, they wanted to know, then where else could they possibly afford to go?

Selectively Beneficial Community Benefits

The question of where residents could afford to go was one that Price and The Reef developers adeptly downplayed by avoiding contact with anyone who might ask it.

They stopped engaging with UNIDAD when it became clear that the coalition would not ease up on demands for meaningful community engagement and the inclusion of on-site affordable housing as well as anti-displacement measures.

Instead, Price and the developers got to knocking on as many as 1,000 doors within a four-mile radius of the project (somehow missing most of the doors in the immediate vicinity of the project, residents charged), gathering signatures in support of the project at community events (where, some have testified, much-needed lunch tickets were traded for John Hancocks and residents were not fully informed about what they were signing), and checking the community engagement box by popping up at random moments, like in adult English as a Second Language classes (where people didn't fully understand what they were being told or why).

They also got to work hammering out important agreements with local unions and tweaking the jobs projections several times over the last year.

In October 2015, Price told ABC7 the project would provide 600 construction jobs. In May, 2016, that figure was raised to 2,700 construction jobs and 600 permanent hotel and retail jobs. At the August CPC hearing, Khalatian both promised 2,800 construction jobs and 750 permanent hotel and retail jobs and also pledged that 30 percent of said construction jobs would be filled by "folks that live or go to school in CD9."

The commitment to hiring within CD9 - coming after a hastily-called and highly contentious May 5 town hall and questions about whether jobs would actually go to any locals - represented a huge shift. The earlier "local hire" provision would have essentially applied to anyone living within Los Angeles County. The new agreement is said to have been formalized in a Project Labor Agreement stipulating that 30 percent of all labor and craft positions would go to workers from within CD9, veterans, or students from local colleges or universities, with special preference for those from L.A. Trade Tech. And The Reef's own website now promises more than 5,200 "direct, indirect, and induced" jobs during construction and 860 permanent jobs.

Finally, the developers agreed to contribute a total of $15 million to the AHTF (up from the first offering of $10 million and a later one of $12 million) to, as Price proclaimed, prevent nearly 1,000 at-risk affordability covenants from expiring. They also agreed to not only spread $3 million in community benefits to organizations located throughout the entirety of Price's district but, in an interesting twist, begin paying out some of those benefits well before the project was even heard at the planning commission (see full benefits list, p. A-1).

It was a winning strategy.

Each time they went up against residents worried about displacement in a public forum, the developers were able to call upon the project's beneficiaries to not only come out in force to speak on The Reef's behalf, but to attack the UNIDAD coalition in the process.

Noreen McClendon the Executive Director of Concerned Citizens of South Central (CCSC) - a group that had already received a disbursement from The Reef to do jobs training - took the first real swing, accusing UNIDAD of sour grapes.

"They showed their butts on this one and are not getting paid," she huffed to the planning commissioners. "Thus the opposition."

"Because this project is getting out ahead of the jobs and providing training to get people ready for the local hire positions, it will...allow them to stay in this community," she continued. But "these organizations [opposing the project] want them to remain poor, destitute...so that they can get money off of their poverty misery!"

She took things a step further at the PLUM hearing, declaring UNIDAD had refused "to talk [with CCSC] about how they can raise their people out of poverty. Why? Because they benefit from poverty. They're poverty pimps and they teach young people to be disrespectful!"

While perhaps the harshest critique leveled at UNIDAD, McClendon's PLUM remarks were only the beginning. Reef supporter after Reef supporter addressed UNIDAD directly in a way they had not at the CPC hearing, chastising residents for being afraid of change, for potentially holding up development, for not having the appropriate mentality, for not listening to God when He told residents to dream big, and for not allowing the community to have its rightful moment in to shine.

South L.A. resident Jesse de la Cruz even called some of the coalition members out by name, asking representatives of SAJE, CD Tech, and the Dreamers of South Central to tell him if they could offer someone like himself - someone who had made some bad choices and done a stint in prison - the fresh start he needed.

The Reef, he claimed, had given him the chance to go back to school and get his life on track.

"Can you offer me benefits that a project like this will offer others that are in the same situation as myself?" he repeated. "Can you?"

The Art of the Deal

De la Cruz's words hung in the air.

It's very hard to argue with residents who are sincere in asking their neighbors for a chance at a job and a better life.

But the fact that the debate had devolved into neighbor against neighbor meant Price and the developers had won: UNIDAD had successfully been branded public enemy number one at PLUM.

And while this clearly bothered those that spoke on behalf of the coalition and the residents they believed were at-risk for displacement, what seemed to trouble them more was that De la Cruz and others had bought into the idea that they had gotten a good deal.

Several Reef opponents cited the Grand Metropolitan - a seven-story, 160-unit residential tower to be built across the street from The Reef - as an example of how much more Price and the developers could have done for the community. Despite being one-tenth The Reef's size, developer Norman Isaac had conferred with neighborhood groups and voluntarily agreed to 24 units of on-site affordable housing for very low- and extremely low-income earners (15 percent of the total units), an on-site workforce that was 100 percent local, and 40 percent local hire during construction. It was, he told KPCC at the time, something he felt was right to do in a community that he could see needed investment. And that while his was "not a big project,...for the bigger projects coming up, it can be a good role model."

Fifteen percent affordable on-site units at The Reef would equal 82 rental units, or 216 total, if the condos for-sale were included in the calculation. Either figure was vastly preferable to the 26 units recommended (and barely approved) by the planning commission in August. Especially on a billion dollar project where the developers had time and again declared that their goal was to “create a sense of place...for all of us to belong to."

Unless you can argue that the residents of the ninth district are somehow ten times less important than those across the street in the fourteenth district, Cynthia Strathmann, Executive Director of SAJE, told the PLUM committee, then The Reef's benefits agreement simply doesn't make sense.

Nor did the argument that a one-time $15 million AHTF contribution would go a long way toward preventing displacement by saving at-risk affordability covenants from expiration and allowing for the acquisition or construction of new units.

For one, as Streetsblog previously detailed in a lengthy exploration here, Price's claims that nearly 1,000 covenants were at-risk and that their expiration posed the greatest threat to area residents were wildly inaccurate, at best.

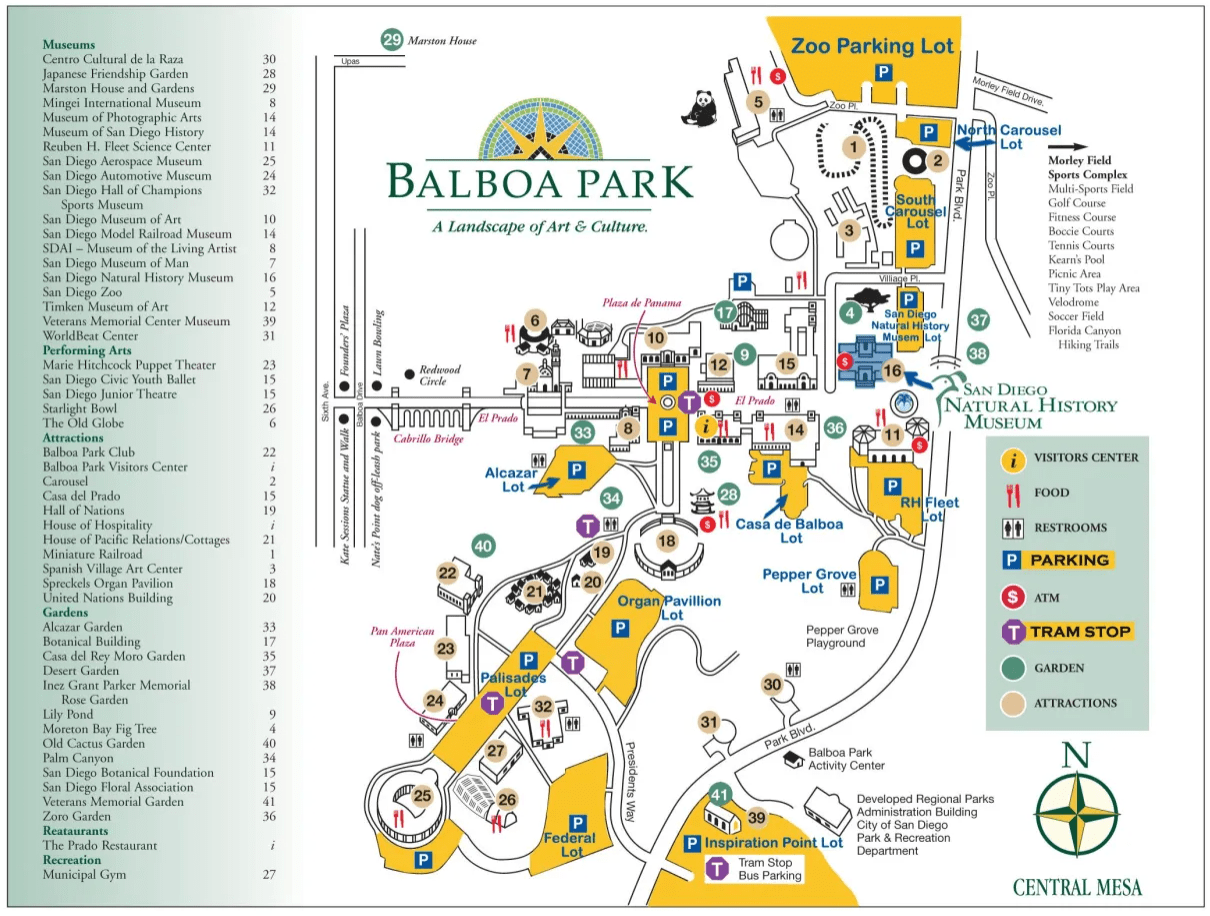

While covenants are indeed at-risk all around the city, they are much less so in Historic South Central (above). Not only are few at-risk sites located within a reasonable distance of the project, the majority of the at-risk covenants found throughout the district are held by affordable developers who are unlikely to turn the properties over. Which leaves just 111 covenants in all of CD9 that are truly at-risk of being lost forever, according to Helmi Hisserich, Assistant General Manager of Housing Development at the Housing and Community Investment Department (HCIDLA).

As such, throwing money and time into extending covenants on properties that are not in any real danger of being turned over would constitute a major waste of the AHTF's limited resources.

Also posing a dilemma is the fact that many of the most at-risk households for displacement in Historic South Central could actually be too poor to access the affordable housing we could acquire or build with AHTF funds (above).

Affordable housing tools tend to target higher low-income brackets - those people earning between 30 and 80 percent of Area Median Income (up to $69,450 in a four-person household). And while many families' incomes fall well below the maximum allowable levels, far fewer earn the minimum income required to qualify for those units - generally three times the proposed rent.

In the case of the new 55-unit affordable development at 722 Washington Blvd. (below), just down the street from The Reef, few units are available at 30 percent AMI. A family wanting to rent a 2-bedroom unit at 50% AMI would likely need to earn somewhere around $30,000 - the actual median income for the neighborhood.

On the rare occasion funding is available to target those earning below 30 percent AMI (approximately $26,050 a year in a four-person household), minimum income requirements can still leave many Extremely Low-Income folks out in the cold.

This disconnect between affordable housing and the ability of needier residents of a community to access it is why there has been so much backlash against affordable housing in Boyle Heights. Some have even called affordable housing projects a form of gentrification because they tend to attract chain retail or restaurants to fill the commercial spaces and serve slightly better-off people, all while failing to alleviate the unhealthy and overcrowded conditions the area's most vulnerable residents continue to endure.

Which is not to suggest that the AHTF funds would be of no benefit to the community. On the contrary - as Hisserich suggested to the CPC, a mix of strategies that prioritized efforts to purchase or otherwise stabilize "naturally occurring" affordable housing might work best to reach the widest group of stakeholders.

But it does suggest that preventing displacement is far more complicated than we think. And the fact that the funds won't even be disbursed to the AHTF until phases two and three of the project doesn't help much, either. By that time, a few years from now, real estate speculation around the neighborhood will already have begun.

For these and a host of other reasons, SAJE's Strathmann asked PLUM committee members to not only reconsider how funds would be spent, but also the total level of benefits being offered. With the passage of Measure JJJ, she said, the entitlements the developer sought would be far costlier. Because the project was being pushed through now, before JJJ's on-site affordable housing requirements could kick in, the developer would be able to realize those savings as profit (especially if they flipped the property) while the community got nothing.

Others opposing the project also spoke up, accusing the city of fast-tracking it to avoid having it subjected to Measure JJJ, accusing the developers of contributing to segregation, accusing both of hiding behind CEQA in order to ignore health issues and the potential for indirect displacement, and venting disappointment at seeing both the developer and the city once again squander opportunities to create a real partnership with the community.

All of which sounded somewhat abstract until Lamar Banks took to the mic and offered PLUM a reality check. His 65-year-old grandmother was in the process of being displaced, he announced, and "I don't see nobody helping her find a spot."

Folks were talking about millions in benefits for the community, in other words, but Banks' grandmother would never have a way to access them.

"We're scrambling right now trying to find her a new place," he said. "She's a senior citizen...she shouldn't be working and, you know, all she's thinking about is how she is going to pay rent at the new spot. And I'm looking at all these other families..." he paused. "I don't see how all these people be here supporting this project when they're about to go through the same thing that my grandma's going through right now."

"I don't see no developers helping her find a new spot," he repeated. "Come on, now."

He paused again to address the developers and Councilmember Price directly.

"Go through these communities and talk to the people who [are]...about to suffer from this. Y'all say y'all from the community. But y'all not in the community."

"Come on, now."

Rarely have three little words encapsulated so concisely what so many people had spent weeks, months, and even years desperately trying to communicate to the city about their circumstances.

Do you really not see how much we struggle?

Come on, now.

Do you really not understand we have no place to go if we are displaced?

Come on, now.

Do you really not see the patterns of displacement in lower-income neighborhoods across this city and this country? How communities of color, their cultures, and their contributions to our cities are erased in the name of revitalization, transit-oriented development, the reclaiming of public space, and livability?

Come on, now.

And yet, in all likelihood, the precedent-setting project that is The Reef will breeze through a council vote today. The mayor will be able to toast the project as bringing him nearly 1,500 units closer to his 100,000 goal and it be lauded as a great victory for livable cities.

At a moment in time when concerns about gentrification, displacement, equity, and justice have prompted more and more people to ask, "But...livable cities for whom?" the easier such questions unfortunately seem to be to ignore.

If the testimonies of South Central residents tell us anything, it is that if we have any hope of building more fair, more inclusive, and more livable cities for all, then we need to be asking ourselves more of those basic sorts of questions more often. The Reef might be the first major project to arrive in Historic South Central, but it is unlikely to be the last project with such transformative potential.

Come on, now.

Find the agenda for today's hearing, here. The council meeting will begin at 11:45 a.m.