Squeezing up on its statutory deadline, Caltrans issued its "Class IV Bikeway Guidance [PDF]" on the last day of 2015.

There are already existing sources of information on best practices and engineering guidance for protected, or separated, bikeways but this is the first from Caltrans. It was prepared in response to the Protected Bikeways Act of 2014, a law sponsored by the California Bicycle Coalition that mandated Caltrans create an official category of protected bike lanes and write guidance for planners and engineers to build them.

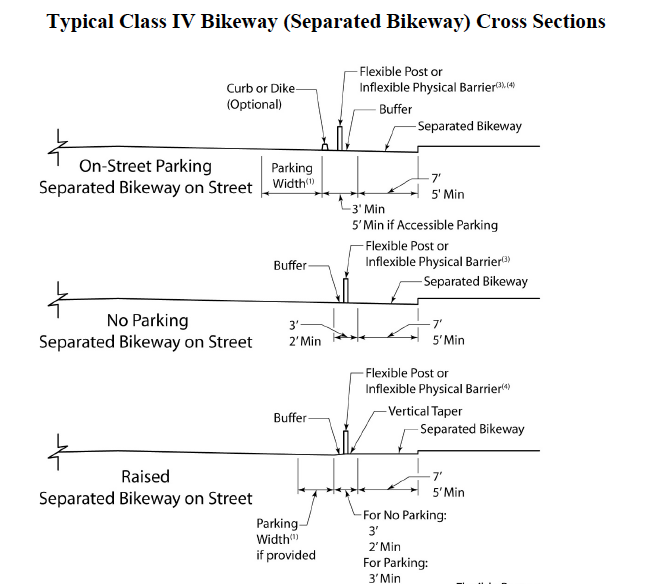

This “design bulletin,” a supplement to the state's official Highway Design Manual, defines various types of protected bikeways, provides examples, and refers to existing publications (including federal guidance) for specific standards.

That Caltrans issued this is a big deal. The lack of official standards for protected bike lanes in California has sometimes been an obstacle for local planners, engineers, and advocates who want protected bikeways. Engineers and planners look to Caltrans for transportation standards, even for local streets and roads that are not directly controlled by the state department. Issuing a set of guidelines that provide background, resources, and consistent standards gives local jurisdictions some certainty about planning protected bike facilities.

To write them, Caltrans engineers relied on new federal guidance as well as other publications including the Massachusetts Separated Bike Lane Planning & Design Guide and NACTO's Urban Bikeway Design Guide.

“We didn’t want to reinvent the wheel—we were thinking the federal guidance is a good broad-based guidance for everything, from building all the way to maintaining facilities," said Kevin Herritt, chief of Caltrans’ Office of Standards and Procedures and the project manager. The writing team coordinated the federal guidance with California laws and regulations. “We have our own requirements that we have to conform to, such as the MUTCD (Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices), and signage standards,” said Herritt.

The first step in developing the guidance was a gathering last May of interested stakeholders, including advocates for bicycling, walking, and disabled communities, city and county engineers and planners, and transportation planning organizations. At that gathering a wide range of perspectives was aired, as summed up in this report. Caltrans formed an external advisory committee representing various points of view. The committee reviewed drafts of the guidance as they came out last fall.

“We're really glad Caltrans is finally doing this,” said Dave Snyder, executive director of the California Bicycle Coalition and a member of the advisory committee. “It shows a real commitment on their part.”

Snyder points out that as a “living document,” the design guidance can keep evolving. “I have a lot of optimism that Caltrans can develop the best guidance in the country, or at least as good as the best guidance,” said Snyder. The new guidance “gets the job done, and even breaks new ground in referring to protected intersections.” At CalBike's urging, the final guidance includes a discussion of how to continue protected bike lanes through intersections, so they do not just disappear as they approach cross streets.

“But it’s still really sparse,” said Snyder of the document, “and could do a lot more to help engineers choose separated bikeways where appropriate. That’s our next step."

Another good thing about the guidelines, according to CalBike's analysis, is that it uses permissive, rather than restrictive, language to encourage engineers to use their own informed judgement when making decisions.

“We didn't want to dictate from a Caltrans statewide perspective,” explained Herritt. “The guidelines are intended to be flexible, so that all local jurisdictions can do what they need to do given their specific local circumstances.”

The statewide guidance, he points out, is “mainly for consistency” so that as you travel the state you know what to expect. “The philosophy behind statewide consistency is that you have the same kind of signage, the same striping, but are still flexible enough to blend into local community needs, and so that users aren't freaked out by unusual experiences.”

One of the benefits of protected bike lanes, said Herritt, is that they work for bike riders who are not comfortable riding with traffic on other kinds of bike facilities. “Caltrans is trying to make sure we get more bicyclists out there on the system across the board,” he said, “and to do so we need facilities available for them to utilize.”

There is still work to be done. For example, the bulletin makes it clear that Caltrans engineers still consider it an acceptable solution to “discontinue” a protected bikeway at driveways or loading zones. Although the permissive language gives engineers some leeway, acceptance of this “solution” to what is a universal design problem could keep bikes at a disadvantage, and could make it harder to create quality bikeway networks in some areas. Where local pressure, habit, or a lack of imagination dictate that it is easier to interrupt a bike lane than solve a tricky design dilemma, that "solution" may end up looking like an acceptable one. Then new bike riders will be left to to figure out what to do when their protected facility suddenly disappears.

As Snyder says, “keep up the good work,” Caltrans. But keep working.