After several years of work, the Governor's Office of Planning and Research (OPR) is almost ready to release draft guidelines on replacing vehicle Level of Service measures under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The shift was called for by Senate Bill 743, which passed late in the 2013 legislative session.

OPR will propose measuring a project's environmental effects with an estimate of how many new vehicle miles it would produce, instead of the long-used Level of Service. LOS, as it is commonly referred to, focuses on how much traffic delay a project might cause. Its use under CEQA has produced many unintended consequences.

The draft guidelines, pending further refinement, are expected to be made available for public comment and discussion in a few weeks. Anticipating the release, Chris Ganson of OPR gave a presentation at a recent American Planning Association meeting in Oakland. There will be another chance to hear Ganson talk about the subject at the California Bicycle Summit in San Diego later this month.

While seemingly obscure and definitely wonky, the subject is an important one: the shift in perspective that the new guidelines call for is likely to have a profound impact on the way development happens in California—perhaps as profound an impact as using vehicle Level of Service has been until now.

Ganson's presentation begins with background: LOS has been used in planning to estimate the effect that projects will have on traffic in the area around it. Estimates are made, numbers are crunched, and in the end nearby intersections are assigned a grade, A through F, which gives a general idea of how quickly cars get through an intersection without delay.

Under CEQA, depending on definitions set by local agencies, a “bad” grade can set off requirements for expensive mitigations, and those have frequently included widening roads and intersections to prevent the traffic delay.

The problems with this are turning out to be numerous. “Auto delay” by itself is not an environmental impact. LOS was supposed to be a proxy for environmental issues caused by traffic, but its focus became primarily on delay of cars at the expense of other things, like delay of people, or energy use, or overall travel (and greenhouse gas emissions) induced.

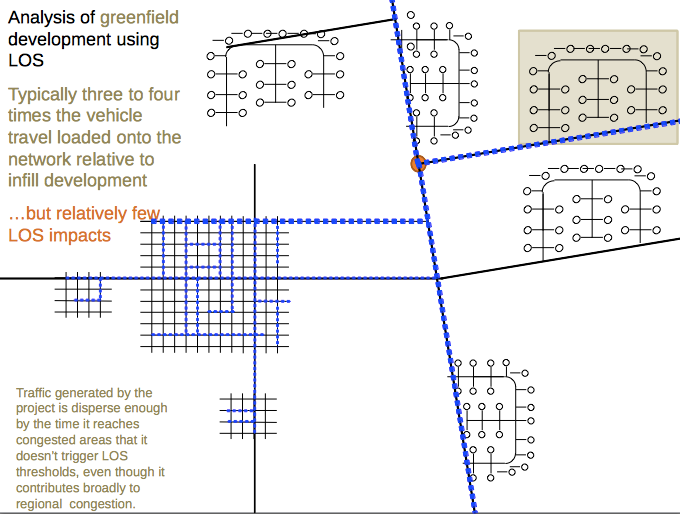

Using LOS, infill projects in already dense areas can show up as having a large effect on nearby intersections, while projects built in outlying areas tend to get a pass. Even if they add more traffic overall to the region, as sprawl projects tend to do, they “look” better under LOS because the impact on specific intersections is less. See the accompanying illustration for an idea of how that works.

In other words, using LOS in CEQA has greatly contributed to the formation of California's sprawling suburbs with big box retail on the exurban edges, inaccessible by anything other than a car.

Instead, says OPR, CEQA should require projects to estimate how many vehicles miles of travel they will induce. That would even the playing field, removing the advantage that sprawl development currently has over infill. Vehicle miles of travel, or VMT, are already being measured and estimated for other planning purposes. Also, California Air Resources Board regulations recognize the need to reduce VMT in order to reach climate change goals, even with an expected increase in electric vehicles.

OPR's proposal is still in draft form, after more than a year of extensive public outreach and many public comments. Some comments support the shift to VMT because it has the potential to address air quality, and promote infill and other development patterns that are not sprawl developments. Some comments expressed concerns, including whether the new measures were mandates or suggestions, and how to set thresholds for CEQA that make sense.

Currently under CEQA, a developer submits an Environmental Impact Report estimating a project's impacts on the area. If the impacts are above a certain threshold, then the developer has to figure out some kind of mitigation that lessens the impact. Thus using LOS, widening a road would reduce delay below a certain threshold—even though it has other unintended consequences. Using VMT, the question is what level of induced traffic triggers the need for mitigation, and what would that mitigation be?

The tension between the need for flexibility and the desire to make a difference—that is, to actually reduce VMT in line with state goals, not just keep levels the same—is part of the reason this process has taken so long and is so complex. OPR's suggested solution is two-fold: to recommend thresholds, rather than set them in stone; and to create a separate technical advisory document that's not part of the guidelines but is meant to help agencies figure out what thresholds should be.

Some key staff recommendations, which are still in draft form and may not end up in the final guidelines, include presuming that projects near transit won't have a significant enough impact to trigger the need for mitigations; eliminating very small projects from the need to produce an EIR; and finding a way to look more carefully at the impacts on transit.

Chris Ganson's presentation at the CalBike Summit will go into all of this in a lot more detail, and his talk is highly recommended for anyone interested in the future shape of development in California. More information about the Bike Summit can be found here.