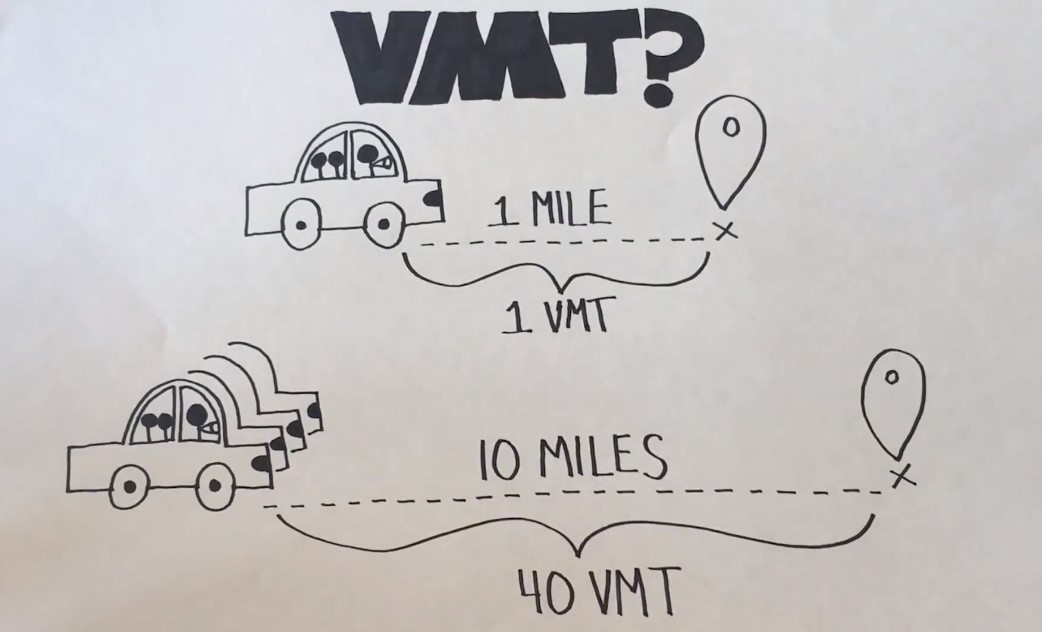

During his State of the State address last week, Governor Gavin Newsom touted reforms to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), claiming progress on housing and environmental review. Yet, a new challenge has emerged: vehicle miles traveled (VMT) mitigation. (Unfamiliar with VMT? Caltrans itself explains what VMT is and how the state is failing to address it - DN)

Under CEQA, some agencies now use affordable, senior, or supportive housing as an off-site VMT mitigation strategy, as outlined in the 2024 CAPCOA Handbook. The logic seems sound, that affordable housing typically generates lower VMT per capita than market-rate housing due to factors like reduced car ownership and higher transit use. However, this reasoning falters under closer scrutiny.

Why Affordable Housing Falls Short as Mitigation for VMT?

At its core, using affordable housing as VMT Mitigation assumes that adding affordable units would offset a project’s VMT impacts. In reality, these projects are additive, not substitutive. Affordable housing does not displace market-rate development since their funding streams are independent of each other. Thus, building affordable units does not reduce the supply of market-rate housing. Instead, it simply adds more households and therefore more travel. If these projects are located in auto-dependent areas, they may even increase VMT. The paradox: projects mitigate their own VMT impacts by funding developments that create additional VMT elsewhere.

Assumptions Are Theoretical

Using affordable housing as VMT mitigation presumes affordable housing always produces lower VMT when compared to market-rate housing. In practice, VMT varies based on many variables, including:

- Project location and access to jobs/services

- Transit frequency and reliability

- Local land use and street design

Fails CEQA Mitigation Criteria

To qualify as CEQA mitigation, reductions must be real, additional, quantifiable, verifiable, and enforceable. The use of affordable housing for CEQA mitigation struggles on all counts:

- Real? No. These VMT reductions are assumed and not measured.

- Additional? No. There is no process in place to ensure that these units will not get built anyways.

- Quantifiable? No. The CAPCOA formula relies on flawed assumptions and limited data, using nationwide averages that ignore local variation.

- Verifiable? No. CEQA lead agencies rarely monitor VMT after a project is constructed.

- Enforceable? No. CEQA lead agencies often lack the authority to regulate the long-term travel behavior.

These deficiencies create legal vulnerability under CEQA case law, which tends to require clear-cut, enforceable mitigation with performance standards.

Policy Implications

If VMT is no longer a reliable proxy for tailpipe GHG emissions, then CEQA may need alternative metrics that more effectively capture mobility and climate goals. As such, policymakers should:

- Revisit VMT thresholds;

- Update assumptions to reflect ZEV adoption and micromobility trends; and

- Consider multimodal performance measures alongside VMT.

Conclusion

Affordable, senior, and supportive housing advances critical equity and housing goals. However, using these projects as VMT mitigation introduces methodological and legal flaws. Lead agencies should reconsider use of affordable, senior, and supportive housing for VMT mitigation, and adopt strategies that genuinely reduce transportation impacts.

Sean Noonan is an environmental planner. He also teaches urban planning at CSU, Fullerton.