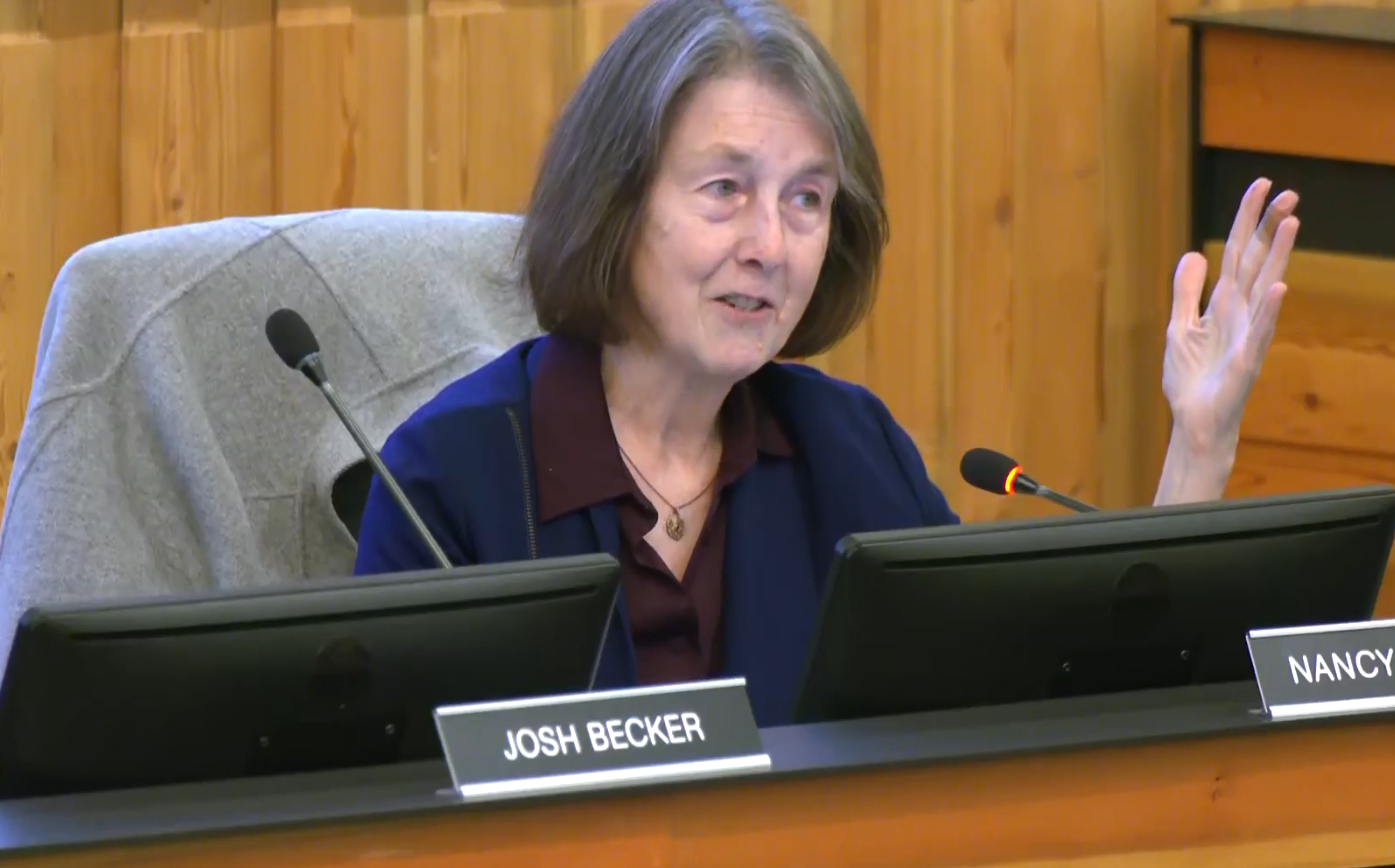

"It seems to me that we are trying to dog paddle here, rather than trying to truly envision a transit system that would help us meet our climate and equity goals," said Senator Nancy Skinner at a hearing of the Senate Select Committee on Bay Area Transit yesterday. "If I am going to ask my constituents to vote on a measure to raise money for transit, then I'm going to be looking for something more inspiring. Only Seamless Bay Area had a vision for that," she added.

The committee was meeting to discuss the current state of transit in the Bay Area - which, with federal and state support has not only stayed afloat but in many ways improved after the battering we all took during the pandemic. Agencies have managed to steadily increase service, improve safety and cleanliness, and moved towards better information systems and wayfinding for their riders. What none of them have done yet is find a sustainable source of funding into the future.

Fiscal Cliff

Which means all the agencies, sooner or later, face what is being referred to as a "fiscal cliff" wherein budget cuts require service cuts which cut ridership which further cuts revenue, leading to a downward spiral that could render public transit pretty much useless.

That situation would bring repercussions far beyond the trouble it would cause transit riders. Dan Tischler from the San Francisco County Transportation Authority outlined models showing that service cuts could reduce ridership by about 100,000 boardings systemwide, reduce the number of jobs accessible by transit - especially for low-income areas - increase car trips, and increase transit crowding. Traffic congestion on the bridges, already reaching prepandemic levels at peak hours, would be congested under any of the scenarios they modeled.

The financial shortfalls would begin in 2026, so "we need to be planning for this now," said Committee Chair Scott Wiener. "Transit is not just a frill; it's not an option. Losing transit would lead to reduced mobility, worse traffic, people being trapped, and completely tanking our climate goals."

The agency heads - from BART, Caltrain, Muni, AC Transit, Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (SCVTA), Golden Gate Bridge, Highway, and Transportation District, Water Emergency Transportation Authority (WETA, who run the ferries), and Contra Costa County Connection, representing a host of smaller operators - gave the committee a summary of the ways they have been tightening their ships, adjusting to changing travel patterns, and responding to rider concerns.

Work Underway

BART General Manager Robert Powers told the committee that all of the agency heads meet by phone every week. "Public transit has never been better coordinated than at this time," he said.

BART's work to "overhaul the rider experience" meant adjusting to fewer peak hour commute trips, running shorter trains, improving headways on nights and weekends, doubling the number of police officers on the system and having them ride trains, along with unarmed ambassadors, which has reduced the number of police incidents on the system as well as the delays those incidents caused. BART is also working on new faregates to prevent fare evasion, and is in the midst of a pilot Clipper Bay Pass program to create a universal, accessible fare card that could be used with any transit agency.

Caltrain has worked on cost containment, said general manager Michelle Bouchard, and the agency redesigned its schedule to adapt to changed commute patterns. But its biggest current project is electrifying its trains, scheduled for completion next fall. "Electrification has been thirty years in the making," she said. When it is finished, the benefits will go far beyond clean, quiet, sustainable energy use. It will allow the system to run faster trains more efficiently, to increase service, and to serve stations that currently only have minimal service, because the technology of electric trains make it easier to start and stop faster and more frequently.

All of the agency heads spoke of adapting to changing travel needs as the pandemic evolved, and of finding ways to speed up service. For example, SF Muni instituted new transit-only lanes which not only sped up their own buses but those of other agencies like Golden Gate Transit. They took advantage of "down time" by redesigning routes, taking care of deferred maintenance (SF Muni rebuilt the subway and has reduced significant delay by seventy percent, according to Director Jeff Tumlin), and piloting new programs like fare capping (CC Connection instituted fare caps that are shared across several small agencies, for example).

A Vision

But Senator Skinner's point about a unifying vision was apt. The only clear vision for a future transportation system good enough to convince voters to tax themselves for it came from the advocates at Seamless Bay Area.

"The characteristic of all successful, thriving public transit systems is plentiful, frequent, useful service, at competitive, reliable speeds, which are connected and have coordinated service and fares," said Ian Griffiths, Seamless Bay Area's Policy Director. "This is only possible with an empowered regional authority that can develop and enforce standards for all transit agencies," he said.

"The Bay Area needs a regional network authority," he added. "This is the norm in places with good transit, even where funding sources vary. The network manager that came out of the Blue Ribbon Committee" - the Metropolitan Transportation Council's prepandemic response to better transit coordination - "has been a good first step, but it lacks authority," he said.

He offered details on why and how to fix this. A ballot measure needs to be linked with the creation of a regional authority, he said, because current governance lacks a mandate, capacity, and leverage, which contributes to the fragmentation of agencies. "And this fragmented experience for the rider has been a real barrier, and has suppressed transit ridership. The lack of a regional authority and capacity also inhibits change" and has slowed past efforts to bring about fare and schedule coordination - which are key to making transit competitive with other modes.

A regional measure should raise between $1 and $2 billion per year for operations and for transformation. It should establish a network manager with the ability to tie new funding to desired outcomes, such as integrating fares and routes. The network manager should also be a new, separate authority with a mix of experts that have relevant experience and current MTC commissioners, but not rely just on geographic balance or elected leadership - and needs to include transit riders.

"These experts are necessary to help build out something that we've never done before," said Griffiths.

Plans to put a regional transit tax measure on the ballot in 2026 are getting a jump start with the Senate Select Committee's hearings - and with the dogged advocacy of outside organizations like Seamless Bay Area, who are handing decision makers a vision they desperately need.