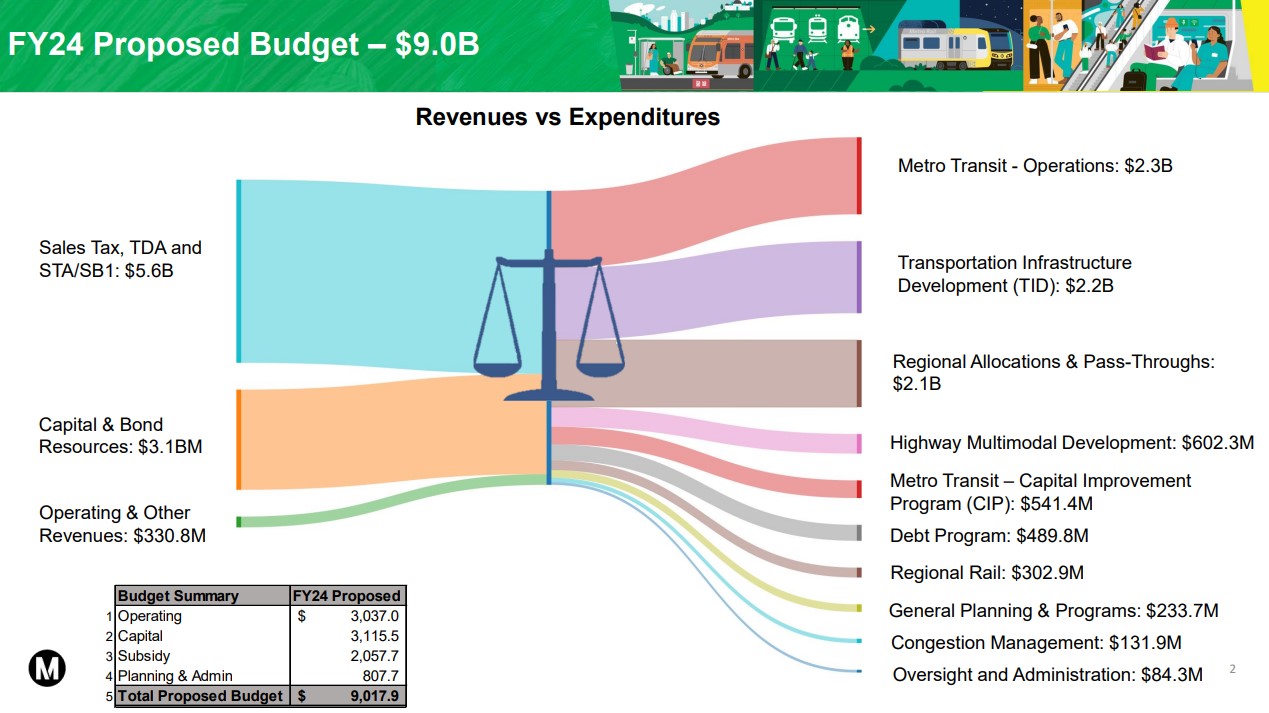

Yesterday, the Metro board approved the agency’s $9 billion fiscal year 2023-24 budget. There is a lot of good stuff in it. Metro’s building rail. Metro is touting modest funding going toward new bus lanes, new on-bus camera bus lane enforcement, and increased money for transit cleanliness and all-door bus boarding.

If you’re looking for a basic press-release-type explainer on the budget, see The Source, LB Post, Pasadena Now, or Daily News. If you want a listicle on some of the budget’s highs and lows, then you’ve come to the right place.

First up, three positives:

1. No fiscal cliff right here right now

The budget is balanced. Metro’s flush, and even carrying over a big surplus.

This comes at a time when transit operators in other parts of California are facing difficulties that are being termed a “fiscal cliff” or even a “death spiral.” Since the pandemic, transit ridership is down all over (though rebounding toward pre-COVID levels). Metro finances transit almost entirely via sales tax revenues, which aren’t dependent on ridership. Many agencies more dependent on fare revenue – BART, Caltrain, etc. – are urgently seeking state funding to stave off problematic service cuts and/or fare increases.

If anything, Metro probably isn’t spending enough. According to the Metro FY23-24 budget book [see pp. 54-5], the agency is carrying forward well over $2 billion in unspent funding, including more than $1.1 billion specifically mandated for transit operations (and other discretionary/flexible money, too). The agency anticipates its surplus will rise to around $3 billion in the year ahead. Sure, Metro needs to keep some funding set aside for a rainy day (which the constant-austerity-preaching budget staff say could happen next year), but right now, Metro probably is not getting money it already has out the door quickly enough. There’s no shortage of operations funding that would constrain Metro from running more transit service, expanding its meager fareless transit initiative, or even upping care-based and/or customer experience initiatives.

2. Metro budget restores rail service

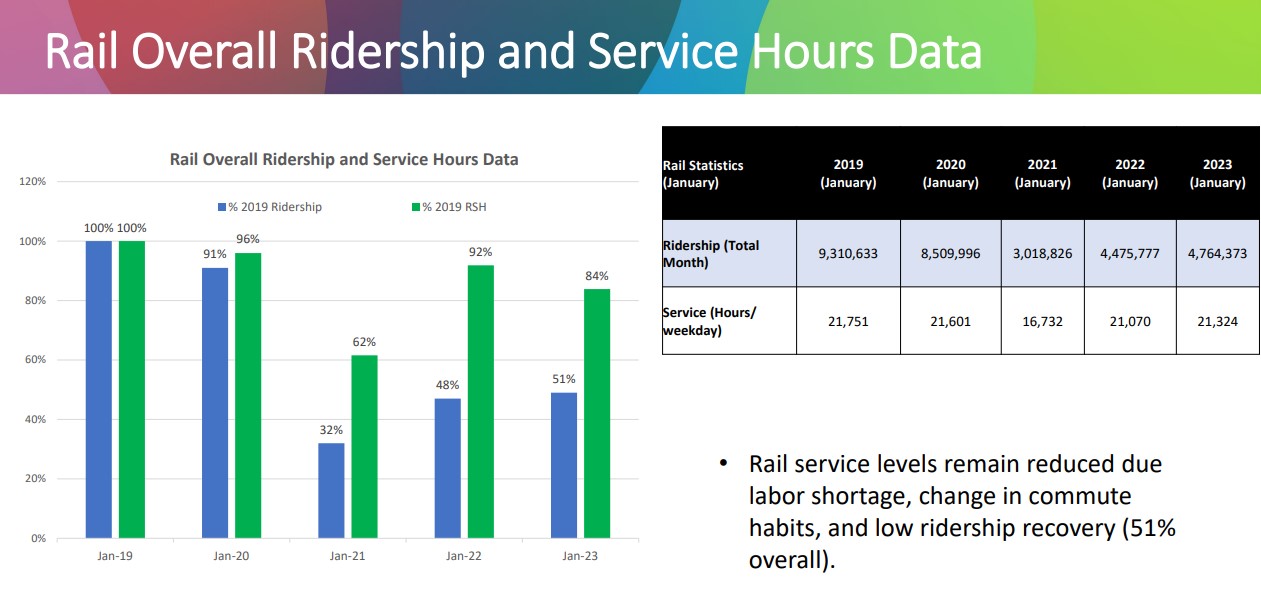

The new budget finally sees Metro restore rail service nearly to pre-pandemic levels. Whew!

Metro cut service deeply at the start of the pandemic, then used a chicken-and-egg rationale (along the lines of “ridership is down, so we don’t need to run more trains”) to never get around to restoring rail frequency to pre-pandemic levels. Not including the newly opened K Line, Metro is operating rail at overall 84 percent of 2019 levels.

The FY2023-24 budget increases rail service by 12 percent, which will bring train service very close to what Metro use to operate in 2019.

Riders should see train frequency increase in mid-July.

3. Metro maintains current bus service

The new budget includes a tiny (0.4 percent) increase in bus service. Last December, after multiple delays and multiple board mandates, Metro restored bus service to pre-pandemic levels. In the past several months, Metro has hired new operators and is just getting excess bus run cancellations to tolerable levels.

After struggling in recent years, Metro’s bus situation right now is pretty good and still gradually improving. This budget maintains that status quo.

And then three negatives:

4. Metro keeps increasing its annual highway widening budget

As Streetsblog reported when the preliminary figures were released, Metro is increasing its annual highway program budget, as it has for several years. For FY23-24 Metro approved $602.3 million for its “Highway Multimodal Development” program, which is 90+ percent highway expansion. Metro notes that this a 4.6 percent increase, but due to some budget reshuffling it’s really a 6-7 percent increase.

Metro is spending billions of dollars to widen more than a dozen L.A. County highways – including planning/building projects expanding capacity on the 5 (multiple projects), 10, 14, 57, 60, 71, 91 (multiple projects), 105, 110, 138, 405 (multiple projects), and 605 (multiple projects) Freeways, and probably more that SBLA missed. Some of these include neighborhood demolitions – underway and planned – in Pomona, Downey, Santa Fe Springs, South El Monte, and elsewhere.

5. Metro keeps decreasing its annual transit construction budget

Metro’s main transit-building budget – the Transit Infrastructure program – shrank in both of the agency’s two most recent budget cycles. For FY23-24, Metro approved reducing it 11 percent to $1.919 billion – the first time it dipped under two billion in the past three-plus years.

Transit construction funding does fluctuate a bit, as some projects close out and others get underway. And there are dozens of other not-quite-mega-sized transit expenditures (bus lanes, Inglewood people mover, etc.) not in this main category. Plus there are quite a few transit projects in the FY23-24 $291 million transit planning budget.

Maybe recent small transit construction declines are nothing to worry about. Or maybe, Metro is having trouble getting rail and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) projects fully designed and funded and transitioned into the construction phase. Contrast this with Metro highway projects, some of which have been accelerated to start construction sooner than their voter-approved funding schedule.

6. Metro perpetuates a problematic transit policing status quo

There has been quite a bit of recent media attention on transit security issues that have worsened over the past year or so, though have arguably been overblown in fear-mongering coverage. With the new budget, the board has largely abandoned plans to shift resources to care-based unarmed responses.

Much of this part of the budget was already teed up over the past couple months. In March, the Metro board approved extending its costly problematic transit policing contract that has been in place leading up to and during the current spike in deaths/crimes. The board also voted to up the transit police presence by approving an additional $6+million to grow Metro’s own police force. Metro did get a well-received transit ambassador program underway (without any shifting of policing funds). The agency has also led with increased policing and other punitive measures in its MacArthur Park Station security blitz pilot.

County Supervisors Lindsey Horvath and Holly Mitchell have tried to hold the line on counterproductive policing (which eats up too much of the operations budget), but they will need more support from the rest of the board to facilitate Metro ever substantially reimagining public safety.