In an attempt to "add a little flavor" to the conversation around bicycle “chop shops” during Tuesday's city council meeting, councilmember Paul Krekorian declared that there were no Metro bike-share bikes at any of the North Hollywood stations right now because "one hundred percent" of them had been stolen.

Krekorian was speaking in support of councilmember Joe Buscaino’s motion asking the City Attorney to create an ordinance taking broad aim at folks who have amassed bicycles and bicycle parts for repair or resale in the public right of way.

The motion, part of what might best be described as Buscaino’s “broken sidewalks” platform - the effort to position himself as The Reclaimer of Streets from Utter Lawlessness as he runs for mayor - was said to be necessary in order for law enforcement to be able to address the larger problem of bicycle theft.

Which was why Krekorian was pointing out the missing Metro bikes.

The only problem was that Krekorian’s claim was not true.

While bike theft has indeed dogged the larger bike-share system over the years (see Streetsblog's coverage here), the North Hollywood system is currently being upgraded. The old bikes are being swapped out for new ones, per Metro. Service has been suspended since mid-January - something Krekorian, who referenced his status as a current Metro boardmember and champion of bike-share during his remarks, would have (or should have) known.

But feelings tend not to care much about facts when it comes to narratives linking homelessness and crime.

So Krekorian went on to argue that the theft of the North Hollywood bikes showed that the city was dealing with "a significant, organized, repeat criminal problem of bike theft" that "just [had] to be addressed aggressively."

Which is apparently why he felt emboldened to tell councilmembers that he had taken matters into his own hands and called the police on an encampment he saw in CD 12.

The bikes Krekorian had seen lined up for sale had not been Metro bikes, as he did not know where they came from. Questions from the police about why he thought they were stolen seemed not to deter him. Nor, it seems, did any consideration of the fact that, although bikes or parts might look viable to a casual observer from a distance, they have often been abandoned or junked by the previous owner for real flaws (bent or cracked frames, bent wheels, bearings issues, etc.), making them fair game for the folks who eke out a living by crisscrossing communities to salvage saleable items.

"I suppose, literally, that's true…I have no evidence that somebody who lines up 40 bikes on a sidewalk, you know, without having a business anywhere in sight - I have no real evidence that those are stolen," Krekorian told council. "But let's get real. We all know that they are [stolen]. And so, if you don't have some way to enforce the law, then we're just going to keep shrugging our shoulders and saying, ‘Oh well, crime like this can just continue.’”

"It's just not OK," he said.

Most reasonable people would argue that siccing law enforcement on lower-income or unhoused people simply because a crime is assumed to have occurred is also "not OK."

The scrutiny people of color, and lower-income and unhoused people of color, in particular, face with regard to bikes more generally is already intense, disruptive, and sometimes fatal. One of the most horrific cases in recent years was the killing of Ricardo Díaz Zeferino in Gardena in 2013. Díaz had been assisting his brother with the search for his bike after it was stolen from outside a market when the responding officer, Sergeant Christopher Cuff, spotted the men and decided they looked suspicious. Instead of engaging them when the men approached him seeking help, Cuff ordered them to get on the ground in English and called for back up. The officers arriving on the scene took their lead from Cuff, who they reported grew increasingly agitated throughout the encounter.

The source of Cuff's agitation was what appears to have been Díaz' attempts to explain to the officers that they were the people that had called police for help. Cuff later claimed Díaz' "furtive movements" and failure to keep his hands raised meant Díaz was “vacillat[ing] between resistive and life-threatening” behavior. As seen in the graphic video, however, it is clear Díaz was frustrated and unsure how to de-escalate the situation. He finally takes his hat off, lowers his arms, opens his hands - a common gesture made in the midst of a misunderstanding - and steps forward one last time. It is at this moment that officers open fire, killing him and wounding friend Eutíquio Acevedo Méndez.

While clearly the worst-case scenario, it speaks to concerns raised by councilmembers Nithya Raman and Marqueece Harris-Dawson about how those targeted by this ordinance would be expected to prove they had not stolen items in their possession and what the consequences might be if they could not.

"It's nice to think about solutions to problems that would never face you," said Harris-Dawson, referencing his own childhood growing up with secondhand bikes that he and his friends would occasionally have to fix in public places. The proposed ordinance would effectively grant law enforcement greater license to hassle youth of color in similar circumstances about where they had gotten the bikes or the parts they were tinkering on.

"It's very different when you have to think about the problems that will be created by - and the jeopardy that you'll be put in by - a policy if you're someone who might be targeted," he said. An ordinance that categorized "anybody fixing a bike on a street that can't prove it's theirs...[as] a criminal" is "absolutely outrageous and beyond the pale."

"Blocking a sidewalk is already illegal. Unlicensed sidewalk vending is also illegal under the municipal code," said Raman, arguing that there were already sufficient laws on the books to cover the scenarios the proposed ordinance purports to address. This kind of "political theater," she continued, was more likely to "capture innocent conduct" while failing to address the actual problem.

One of the many reasons Buscaino's move does indeed feel like theater is that no data has been offered with regard to the scope of the problem. Data on bike thefts is wildly inaccurate at best, and council has yet to get more concrete information on the actual number of "chop shops" beyond "we've seen a proliferation."

The blanket nature of the ordinance would also impact vendors like César, whose van is pictured at the top. When I met him a few years ago, he told me he was already regularly hassled by police about his wares. That scrutiny was the reason he tended to get his goods from the junkyard, he said. Though he was not averse to buying goods off community members who needed the cash, he said he did his best to avoid buying bikes he believed were stolen. Many such vendors have a long history in the community - serving some of the lowest-income residents who could not otherwise afford bikes for their children and providing parts, tools, and repair assistance that is often in short supply in disinvested communities. They've long had to contend with being hassled by law enforcement, but now their livelihoods and the services they provide could finally disappear for good.

Unhoused residents who provide similar services - including repairs essential to keeping their community rolling - and rely on that work to make a legitimate income would also be targeted.

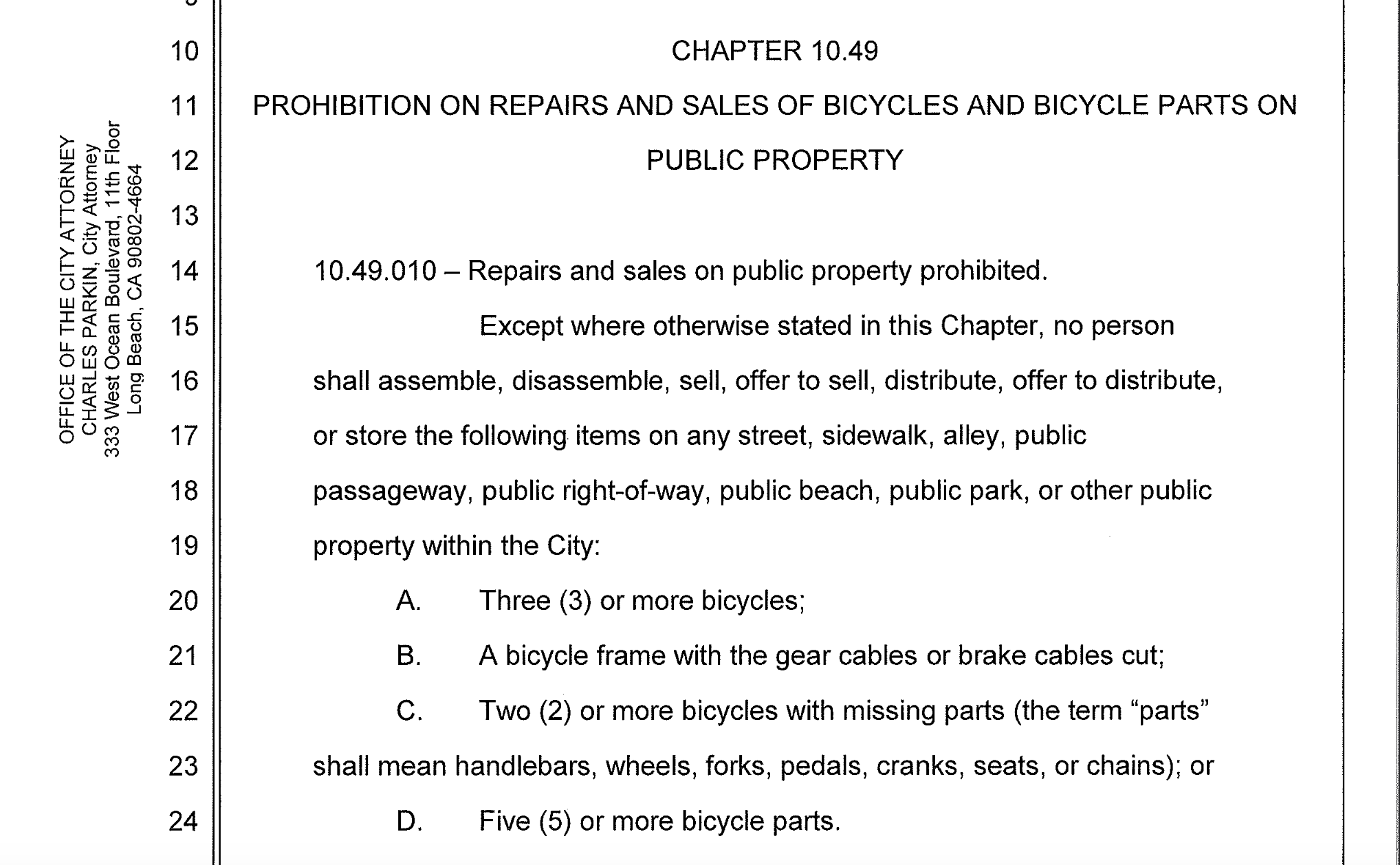

And as alluded to by Raman in her remarks, an ordinance inspired by the one implemented by Long Beach (below) would go well beyond existing laws to govern what people could or could not possess, putting residents of many encampments at potential risk of having their means of transportation confiscated.

Not only does the Long Beach ordinance disallow the assembly, disassembly, sale, offer to sell, distribution, or offer to distribute three or more bikes, a frame with the cables cut, two or more bikes with missing parts, or five or more bicycle parts, it also prohibits the storage of such items.

Refusing to be "a silent extra in the background" of this "campaign commercial," councilmember Mike Bonin pointed out the hypocrisy of the city having turned over the public right of way to bike and scooter companies in Buscaino's district before it had hammered out a plan that would make the practice legal. To now craft an ordinance aimed at curtailing the ability of unhoused people to own or fix a bike - "I think there's something wrong with [that]," Bonin said. The instrument was too blunt, the goal too unclear, and it was just the wrong way to go about dealing with the issue of bike theft, which he said was a legitimate, but separate, issue.

Buscaino did not take kindly to the pointed remarks of his colleagues regarding his motives. But then he quickly went on to make what sounded very much like a campaign speech, while also effectively laying bare that the ordinance was more about clearing the sidewalks.

Declaring he was "miffed" that some of those objecting to his motion had also objected to ordinance 41.18 - the controversial ordinance that banned sitting, sleeping, lying, or camping in the public right of way in specific locations - he asked if "we [are] sending a message that anyone anywhere in the city can block any public right of way that belongs to the public? Or [if] we are sending a message [that] thieves have free reign?"

"This ordinance does not criminalize homelessness," he declared. "It criminalizes conduct that is the direct result of [people] failing to support their drug habit. We as a city need to stop enabling drug addicts."

The claim that there is no intention to criminalize homelessness is difficult to square with the fact that the man making that claim has proposed putting a measure on the ballot that would effectively criminalize those that "refuse" shelter, regardless of the legitimacy of the reasons a shelter offer might be turned down. Or with the fact that he has also held press events in districts where homelessness is more visible to criticize his colleagues' failure to take as hard a line as he is willing to draw on the issue. Or with the fact that his idea of a good giggle appears to be humiliating an indigent person in front of a reporter by asking if the man intended to go drinking with the five dollars Buscaino gave him.

As he concluded his remarks to council, Buscaino attempted to remind viewers that he was just a boy, standing in front of a city, asking for it to love him by way of agreeing the streets had been taken over by lawlessness and criminal enterprise.

"Political theater, members, my goodness! It's gonna be a long 11 months [until the Nov. 2022 election]. A warning to members who are running for election, reelection, or another office: if you put forth a motion and want to improve our quality of life in Los Angeles, that's political theater. I call nonsense on that."

Indeed.

_______

The motion passed with ten votes. It will next head to the City Attorney's office, where the potential ordinance will be crafted before being returned to council for more discussion and debate. See the motion and other relevant documents here. Watch the full council meeting here.