Content warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of police violence. Links are provided to the LAPD briefing videos, but the videos are not posted here. The one clip included stops prior to shots being fired. This story also includes discussion of suicidal ideation and self harm in service of examining the LAPD's response to those in crisis. Please proceed with care. If you or someone you know is in crisis, please call the national suicide prevention hotline: 800-273-8255.

Forty, stand by!

The warning rings out as 22-year-old Margarito "Junior" López stands up and begins to pace in front of the apartment building where, for the past several minutes, he has been sitting and intermittently holding a meat cleaver to his own throat.

The signal is meant to alert officers on scene that a “less lethal” 40mm projectile is about to be deployed and that, per protocol, they should wait to assess its effectiveness. The same warning had been given several minutes earlier, just prior to the firing of a projectile at López when he first stood up at the top of the stairs.

This time, however, it goes unheeded.

Half a second after the projectile is fired at López - who is in the midst of turning away from officers and back toward the steps - officers José Zavala and Julio Quintanilla fire four live rounds in a burst of contagious fire, including one after López was already on the ground.

Notably, LAPD elected not to include the standby warning among the other transcriptions provided in the Critical Incident Briefing for the December 18 “officer-involved shooting” that killed López.

Nor did they include any BWC footage from the officer who issued the warning and fired the "less lethal" weapon.

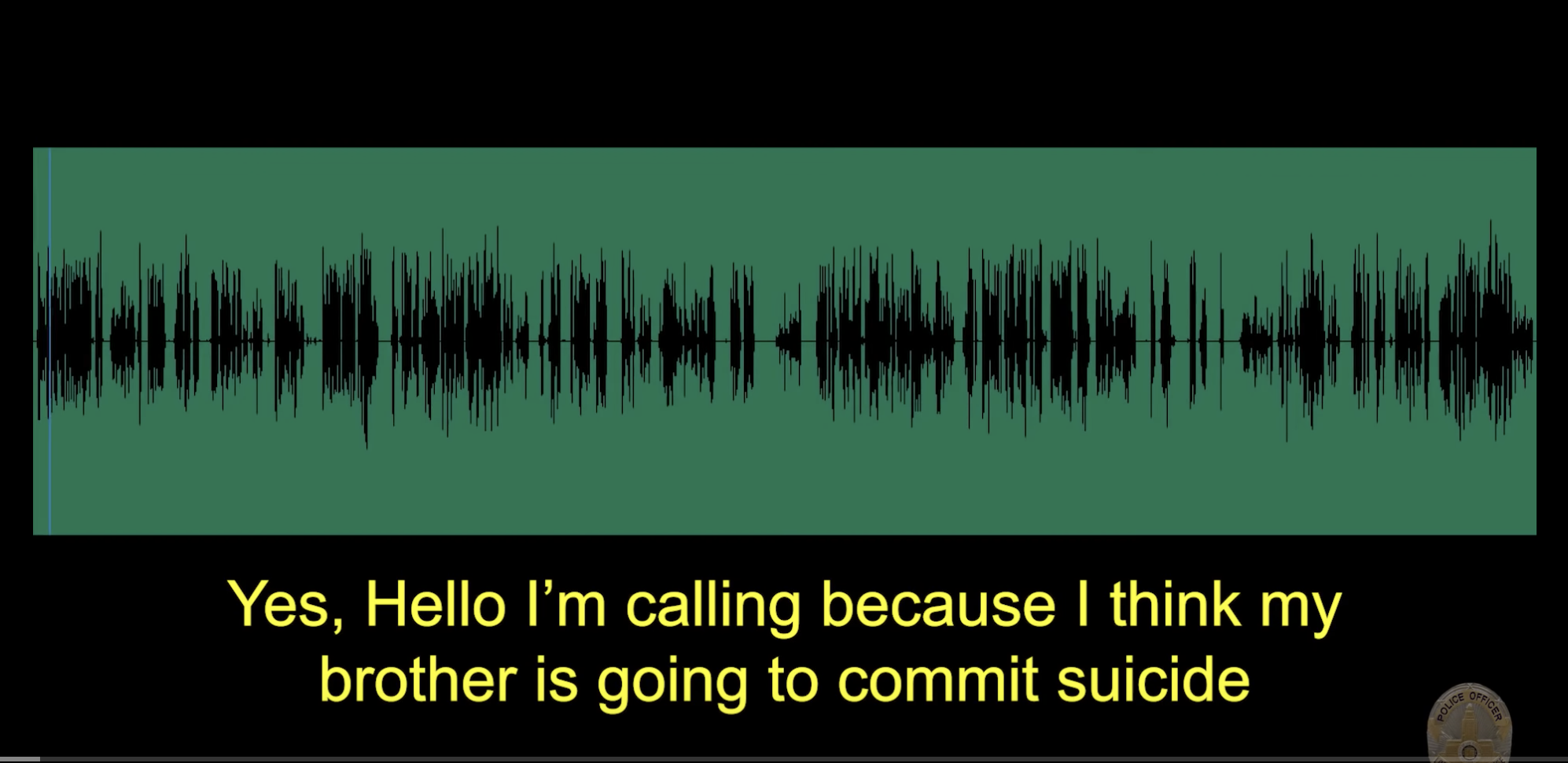

The only footage provided is from officers José Zavala and Julio Quintanilla - the two who fired live rounds. [Note: The clip below does not include the shooting. To help isolate the warning, the clip has been slowed down to .75 speed and the caption has been added in green. The warning can be heard at full speed at about minute 14:50 and minute 24:26 in the full Briefing video.]

It’s not hard to see why the warning was omitted.

Highlighting that it went unheeded would mean acknowledging that the cacophony generated by LAPD’s massive and uncoordinated show of force in response to a young man of color in crisis created the perfect conditions for contagious fire to erupt.

When asked if LAPD would be releasing the body cam footage from the officer who issued the warning and fired the “less lethal” round, media relations officer Drake Madison answered in the negative and pointed this reporter back to the Briefing video, describing it as “a thorough explanation of what took place.”

The Briefing is far from thorough.

But the narrative LAPD has carefully constructed around select footage does indeed offer their version of an explanation: namely, that López bears responsibility for his own death. As Captain Stacy Spell explains, López "continued to refuse to comply" with orders to drop the cleaver, and "advanced toward the officers, which resulted in another 40 millimeter less lethal launcher foam projectile deployment and a simultaneous officer-involved shooting."

Unpacking the encounter

While speaking to KPCC's Larry Mantle about the shooting last week, LAPD Chief Michel Moore said that although he was confident that his officers’ efforts that day "were to try to safely resolve and de-escalate” the situation involving López, a mental health team should have been dispatched.

But Moore also said he didn't know if the outcome would have been different if such a team had been on the scene.

In contrast, the extent to which LAPD has actively worked to keep this incident under the radar from the outset suggests the department is very aware both of just how little de-escalation there had been that night and how differently it should have been handled.

Though notices of “officer-involved shootings” are normally posted to social media via the Public Information Office’s twitter feed, López’ killing was not among those mentioned on December 18.

That night, details given to news outlets scrambling to cover both López’ killing and the shooting earlier that same day of another man with a knife, Rosendo Olivio, Jr., also remained scant. An LAPD spokesperson told ABC7 only that after getting a call about “a man with mental illness,” police had encountered “a man in his 20s with a knife who had allegedly been chasing people down the street.”

The official press statement on the killing was finally posted five days later - just before Christmas Eve. In it, LAPD implies that the ineffectiveness of the foam projectiles in getting López to stop coming at officers with a knife had forced them to resort to live fire. The posting of the Critical Incident Briefing to the LAPD’s YouTube channel on January 14 - the Friday before the Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday weekend - also seems to have been timed to hide it. Notice of the Briefing release was never posted to the twitter feed of the Office of the Inspector General, where they can usually be found.

News Release Update: pic.twitter.com/jRXV9R4AHp

— LAPD PIO (@LAPDPIO) December 24, 2021

Despite all that, and despite the effort LAPD put into crafting a story of an aggressor who would not comply, the images captured in the Briefing video still beg the question of why there was such a rush was to gun down a beloved young man who had been surrounded by overwhelming force, no longer posed a threat to community members, was in distress and holding a cleaver to his own neck, made no threatening moves toward officers, and was actually turning away from officers when they opened fire.

It had been made clear in the first 911 call that López was in distress and possibly suicidal. He had frightened his family after locking himself in the bathroom with a knife, but he had also scared them enough that his father told him to leave the apartment.

Once López was in the street, he also apparently frightened and chased neighbors, resulting in more calls to 911.

But it appears that by the time the first two sets of officers arrived, López had retreated to the top step of a small apartment building, where he sat quietly twirling a cleaver near his own throat.

Captain Spell, whose narration sets the scene for what viewers are about to see, describes the officers as having "attempted to establish communication with López in both English and Spanish."

There is very little in the way of two-way communication.

In between telling him they are there to help, the officers repeatedly shout at him to drop the knife. The only question asked of him is his name. There is no call for a mental health team - only calls for more back up, for traffic control, and for an ambulance to be on standby. Then more police and a helicopter arrive, adding to the cacophony.

All of this is happening while at least two blinding lights, one (and possibly two) "less lethal" weapon(s), and at least three guns are pointed at López.

López points the cleaver at his own throat several times, appearing to be ready to slice himself.

Then, two minutes into the encounter, he suddenly stands up and again gestures at his throat.

A flurry of communication happens among the officers as they call for a "less lethal" to be deployed. A standby warning is then given just before one of the officers - seen on the driver's side of the far vehicle - fires a 40mm projectile at López.

"Bean bag only. Bean bag only," says either Zavala or Quintanilla; they and at least one other officer still have their guns trained on López.

For his part, López seems more focused on whatever he is going through. Still holding onto the cleaver, he slowly descends to the bottom of the steps and sits down again.

There are more self-slicing gestures and more pleas for him to drop the weapon from police and his family, friends, and neighbors.

Suddenly López stands up for a second time and takes a couple of steps - first forward, then to his right, then turning back to his left as if to go back to the steps - all the while holding up the cleaver like he's in a marching band.

His behavior is unusual - almost childish - but it is clearly non-threatening. He's holding the cleaver so high that it gleams in the high beams trained on him.

Apparently recognizing the behavior as non-threatening, the officer with the "less lethal" calls out, "Forty, stand by!" and prepares to fire at López' back.

But there is no order anymore: sounding fearful, either Zavala or Quintanilla yells at López not to walk in his direction while the other yells, "Stop! Stop! Stop!" Others in the background also continue barking orders.

López does not walk in their direction. Nor does he point the knife at anyone. But when the 40mm projectile is fired at López' back a moment later, Zavala and Quintanilla open fire immediately, firing four live shots. One of them (the passenger officer) fires his final shot after López is already on the ground.

Just over eight minutes have gone by since officers first arrived on the scene.

A la brava

As seen in video captured by bystander Kishi Hundley, the large crowd that has gathered is utterly distraught. A man drops to his knees in the middle of the intersection. Others scream, "Junior!" Still others demand to know why officers shot him and why they are putting the now unarmed and bleeding youth in handcuffs.

At a vigil covered by Univisión's Julio César Ortiz, the family continued to question why LAPD responded "a la brava" - leading with force - rather than the compassion and communication that López, who they say was intellectually disabled, deserved.

Margarito López fue baleado mortalmente este fin de semana cuando agentes de LAPD llegaron al área de Adams Boulevard y la Avenida Griffith, donde reportaban a un hombre armado con un cuchillo.

— Univision LA (@Univision34LA) December 20, 2021

➡️ https://t.co/YUsX0Vz13s pic.twitter.com/7Qpc3JUQW4

But "a la brava" tends to be the norm, rather than the exception.

"I don't think police try to understand the situation," 28-year-old South Central resident Rubin Cornett says of the encounters between police and those in crisis. "They take all situations and put it in the same category: threats. But when the knife is turned on me, I am a threat to myself, not them."

Cornett would know. He was in several such situations himself in his early 20s - including at least one where SWAT was called. The trauma of an abusive home, a youth spent bouncing between dozens of foster placements, and a lack of access to mental health care meant that he had arrived at adulthood with few coping skills. As a result, when he was pushed to his absolute limits by overwhelming waves of rage, pain, and fear, he would sometimes grab a knife and threaten self-harm.

Imperfect a solution as it was, grabbing a knife gave him leverage in those moments - it was the one way to try to make everything stop so he could finally express and find some relief from his pain. But the first and only concern police always seemed to have when confronting him was the whereabouts of that knife, not the reason he grabbed it.

At least with SWAT, Cornett says, somebody tried to talk to him to figure out what was going on. But in incidents where just regular police showed up, they immediately pulled their guns on him (including during a harrowing 2018 episode this reporter was on the phone with him throughout; it had been triggered by a fear that his then-girlfriend was going to kick him out of her apartment, leaving him homeless).

"I feel like [LAPD] having a gun is strike number one" against a peaceful outcome, he says, asking why that is the first response rather than de-escalation, tools other than guns, or sending the kinds of mental health officers who always evaluated him at the station after he was detained.

Because they always approached him like he was a threat, he says, "I was afraid they was gonna shoot me, regardless of whether I dropped the knife or not." And then blame him for it by suggesting they had fully exhausted their options.

“When given an option, we always want to use the minimum amount of force needed," Detective Meghan Aguilar told KTLA on the night of López' shooting, explaining how police had used "less-lethal" rounds before resorting to firearms. "Ultimately though, as the situation escalates, we are at times forced to use lethal force, as we were this evening.”

It's a claim that implies a) that officers had methodically paused to assess after the second "less lethal" was fired before firing live rounds and b) that there was a clearly communicated de-escalation plan that was being followed. But neither appears to have been the case.

Instead, what can be seen in the moment is how surprised the officer who fired the 40mm projectile appears to be at hearing live rounds being fired (below). As captured by the BWC of the driver officer, after firing the "less lethal" round (left image), he immediately turns his attention away from López and toward Zavala and Quintanilla (right image).

"Advancing towards officers"

As part of the larger effort to reimagine public safety, L.A. has taken some (very) tentative first steps toward the building of an alternative response system for those in crisis. Among them are the triaging of 1,857 crisis calls to Didi Hirsch counselors in 2021 and the dispatching of CIRCLE teams - via the (limited) Crisis and Incident Response through Community-Led Engagement pilot program - to nonviolent calls involving unhoused people in Hollywood and Venice.

But, as noted in the L.A. Times, crisis calls where the individual "threaten[ed] to jump off a structure or run into traffic, needed emergency medical attention, had a weapon in a public place or with people present or posed another public safety risk" would not be among the diverted calls.

That means that the cases where de-escalation is needed most will likely continue to be met with an antagonistic approach instead.

Even though mental health calls that culminate in a use of force represent a relatively low percentage of the total number of such calls - about three percent (550 incidents) in 2018, according to the Times - they are overrepresented in the total uses of force logged by the department.

It's not just an issue in L.A. Statewide, half of the uses of force that resulted in injury, death, and/or involved a firearm were calls where the subject was described as "erratic," impaired in some way, or mentally disabled. Nationally, cases where mental health was said to be a factor comprised nearly 30 percent of the police shootings last year. Here in L.A., the numbers are even more grim: according to the LAPD's own report, "more than half of the [37] officer-involved shooting incidents [in 2021] involved individuals experiencing a mental health crisis."

One of the (many) barriers to seeing things change in this regard is the success both LAPD and the Sheriff’s department have had in shaping the narratives - and by extension, public debate - about the outcomes of these encounters.

The strategic criminalization of the person in crisis - labeling them as the “suspect” while minimizing the roots of the crisis - keeps attention focused on the threat that person allegedly represented to and/or the fear they provoked in officers.

It also makes the subject's behaviors more weaponizable. A step toward an officer is an “advance,” implying an offensive threat. People carrying implements - either real or perceived - are said to be "armed" or "knife-wielding," regardless of what their intention with the implement was. Failures to respond to orders out of fear, panic, anxiety, confusion, or distress are a "refusal to comply" and, ultimately, a justification for a use of force.

The Briefing video for the December 26 killing of 33-year-old Enrique Ruiz, Jr. at an Eagle Rock gas station offers one example of just how far that framework can be stretched in service of deflecting criticisms of LAPD.

The video depicts the kind of encounter that presents a true challenge for responders - one where the fire department called LAPD for assistance because Ruiz’ insistence on hanging onto the blade he had sliced himself with made it too difficult for them to render first aid.

When Ruiz finally emerged from his vehicle, dazed and soaked in blood, he continued to hold onto the massive knife, but kept it pointed downward as he shuffled slowly toward officers with his arms outstretched, asking them to shoot him.

Eventually they do.

It’s a shattering scene, both because it put officers in a position that they clearly were not equipped to address and because of the obvious and extreme distress that Ruiz was in.

It’s also the kind of scenario that needs to be included in the conversation about the parameters of a more robust alternative response infrastructure, for the well being of first responders and folks in crisis alike.

But rather than acknowledge the challenges a case like this presents in the Briefing, LAPD added cell phone footage from a neighbor in an apparent effort to support the claim that Ruiz was asking police to shoot him.

It's wholly unnecessary - Ruiz' request can be heard in the cam footage. Nor does it not justify the shooting in any way, as people in distress do make such requests precisely because they are in crisis.

Instead, it conveys a genuine callousness toward both Ruiz and the distress he was experiencing.

Reflecting on his own encounters with police - including one where this reporter heard him yelling about how he was ready to die because he didn't want to go to jail - Rubin Cornett says he is still "shocked that [he] was not shot dead."

Thankfully, he says, that headspace feels like a lifetime ago. In the intervening years he's worked hard to keep himself moving forward, hold two jobs at a time, stay sober, and stay focused on the positive. Personal tragedies, including the murder of his younger brother last summer, have not made that easy. He’s found himself on the verge of losing it more than once, he says. But the coping and communication skills he has worked so hard to sharpen have kept him safe and feeling stronger every day.

"A lot of people don't understand where I came from," says Cornett. "I get choked up thinking about how far I've come. I'm surprised at myself - my mindset has changed." So much so that he aspires to mentor foster youth like himself to show them that they, too, can survive both the system and their struggles and go on to thrive.

What he doesn’t want is for other youth to find themselves in crisis in the middle of the street, having to hope that the officers pointing guns at them will care enough to see that they're just in pain, he says. "Half of these people just need someone to talk to."