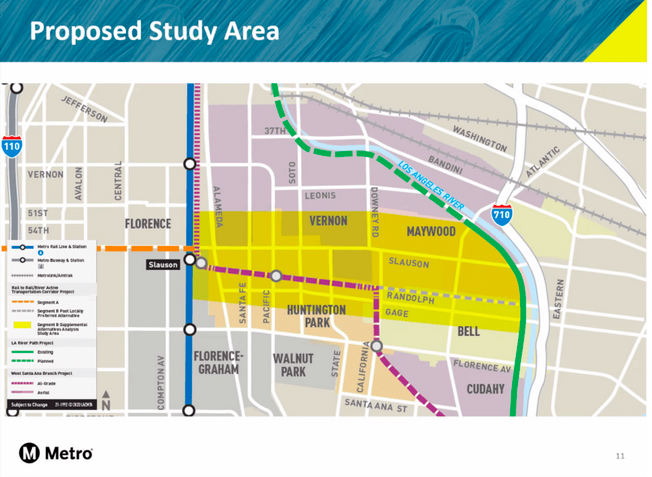

On January 27, Metro held a Community Advisory Committee (CAC) meeting on Segment B of the Rail-to-River project to relaunch the community engagement process around preferred routes for the bike and pedestrian path meant to create a seamless connection between the Blue Line and the river through the Southeast cities. To that end, Metro will be holding two community meetings this week, one tomorrow evening and one on the 13th (details at the bottom of this article).

The impetus for the relaunch was the determination that part of the Randolph St. route - originally identified as the preferred pathway in 2017 - was no longer viable. The planned West Santa Ana Branch (WSAB) rail line, connecting the southeast county to downtown L.A., will run along a 2.3-mile section of Randolph in Huntington Park instead.

Though the Randolph right-of-way (ROW) is quite wide, Union Pacific (UP), who owns the ROW, has no plans to remove its tracks. The WSAB rail infrastructure will therefore have to be built alongside the existing tracks (seen below, in a section of Randolph on the west side of Huntington Park), leaving insufficient space for a bike path.

The news of the change comes as an unwelcome surprise.

For one, it substantially alters the nature of the project.

First proposed in 2012 by then-Metro boardmembers Mark Ridley-Thomas and Gloria Molina, the Rail-to-River project aims to convert a right-of-way (ROW) deemed infeasible for passenger rail into a community asset in an intensely park-poor section of South and Southeast Los Angeles. It was envisioned to serve as an "active transportation corridor" - a way for commuters to easily connect to key transit lines via a bike and pedestrian path while also creating a ten-plus-mile corridor inviting residents to bike, roll, skate, jog, and stroll with their friends and family.

Segment A, the 6.4-mile “rail-to-rail” portion of the project, will largely follow Slauson (along the Metro-owned ROW) to facilitate transit users’ movement between local bus lines, the Silver Line, the A/Blue Line, and the soon-to-open Crenshaw Line.

On the east end, the Slauson ROW disappears just before Alameda, necessitating a separate plan - Segment B - as well as coordination with both a different ROW owner and the Southeast cities that segment will continue on through.

One of the reasons Randolph (B4) had first emerged as the preferred route was that the wide ROW offered users protection from the traffic on either side of it. It also would have taken users directly to the river and it is already utilized by some in the community as a jogging path.

The other routes floated at the time couldn't measure up. There are no good east-west alternatives through Huntington Park that offer the possibility of a separated bike path or protected facility without significant changes to busy, fast-moving corridors like Slauson (below).

While a Slauson route (B3) offered more direct connections to schools, back in 2016, Metro said the best it could have offered users there was an unprotected bike lane. The Malabar and Utility Corridor routes (B1 and B2), running north through industrial areas (and away from residential ones), would not have connected users to as many destinations or enhanced connectivity between the Southeast communities.

Of the previously studied alternatives, only Slauson really remains in the running. That said, the route can still be designed to plug back into the Randolph ROW east of State St. (below), as it moves into Bell.

Rather than talk to the Community Advisory Committee about how to work around the problem the WSAB overlap had created, the potential alternatives, or even the possibilities that remained along Randolph (e.g. was a road diet/bike lane a possibility there?), Metro said it was relaunching its community engagement process from scratch.

To that end, staff offered up several maps (including this one of planned routes in the Southeast cities) suggesting the possibilities for a new Rail-to-River path were now wide open.

Meanwhile, the fact that Bell is already looking to install either a shared-use path along Randolph or a walking path and protected bike lane (seen below) as one of its "priority projects" was never mentioned.

The apparent lack of coordination and the framing of the process as a "relaunch" frustrated some of those present at the CAC meeting, most notably representatives from Communities for a Better Environment (CBE). Why, they wanted to know, were stakeholders being asked to retread the same ground on a project that had already been in the works for eight years?

Metro representatives for the project have said that they do currently have active working groups with the relevant Southeast cities. But the survey Metro walked CAC participants through reads as if Metro is coming into the community for the very first time.

Instead of building on data gathered at prior Metro meetings (and via a very similar survey back in 2016) or during the recent bike plan planning processes in Bell or Huntington Park, the form asks for the very basics, like residents' biking and walking habits.

It also asks stakeholders for input on how they would use a facility without specifying whether the facility is a protected bike lane vs. an unprotected bike lane or a bike route or a walking path vs. a regular sidewalk.

Similarly, rather than trying to create a richer picture of mobility needs by asking stakeholders to confirm or add to the existing collision data (e.g. this collision map from the HP bike plan)...

...or by drilling down to see if there were other factors impacting folks' sense of safety, the survey asks them to fill in a blank map.

Participants are also asked to fill in key destinations on another blank map rather than add to one where destinations and community assets are already mapped out, akin to the one in the HP bike plan (below).

It all makes it hard to see what kind of insights Metro is fishing for or how it might use whatever data is gathered to narrow down a pathway.

And again, given that both HP and Bell's bike plans offer a baseline with regard to priority routes, important destinations, current commuting habits, traffic volumes on key corridors, collision data, self-reported barriers to bicycling, and data offering a reminder that any facilities should also support skateboarding as a mode of transportation, a broad, haphazard survey makes it feel like Metro is simply checking the community engagement box.

As it is, Metro hasn't had the greatest track record when it comes to engagement around the Rail-to-River project - both the South and Southeast L.A. communities were held at arm's length throughout much of the planning process.

Early on, Metro defended the decision to do minimal community engagement around the feasibility study by saying it didn't want to get the community's hopes up about the project. But as planning for the project progressed, Metro did little to invite wider community participation.

Streetsblog often critiqued that process - notably the disconnect between Metro's idea of a bare-bones transportation corridor serving folks connecting to transit and stakeholders' desire to see a project that felt like it was made for them and that served their community without accelerating gentrification. Other issues of note included Metro's stubborn reluctance to engage, create space for, or collaborate with corridor stakeholders to build a vision of a project that was truly community-uplifting.

It was disappointing, for example, to know Metro was not communicating with or trying to design space for the vendors - many of whom had worked on Slauson for well over a decade and whose livelihood depended on access to the corridor (above) - but had incorporated open space that could accommodate "farmers markets' and other pop-up events" and "food trucks and dining on special nights" into the design (below).

While seeing Metro relaunch Segment B's planning effort is disappointing, it does provide Metro the opportunity to do better by stakeholders this time around, particularly when it comes to the design phase.

As of now, Metro is looking to move through the selection of an alternative route rather quickly - it hopes to have narrowed down a set of alternative routes by spring and decided upon a final route this summer. Some of the factors that Metro says will figure into its final decision include the route's directness, cost and ease of implementation, and alignment with community input, needs, and aspirations.

If you'd like to hear more about Segment B, Metro is holding two informative community meetings this week to move that process forward:

Thursday, February 11 from 6 - 8 p.m.

Zoom Link: bit.ly/3slRVrZ

Meeting ID: 940 6249 7697

Passcode: 5851

Call-in: 669.900.6833

Por teléfono en español: 646.749.3122

Contraseña: 489 265 621

Saturday, February 13 from 10 a.m. - 12 p.m.

Zoom Link: bit.ly/3ozXyAm

Meeting ID: 929 4003 1423

Passcode: 5851

Call-in: 669.900.6833

Por teléfono en español: 571.317.3122

Contraseña: 214 331 069

As for Segment A, the construction bid should be released later this spring. Ground should have been broken on that segment in mid-2018, but the project had stalled when bid proposals came in too far above budget. Metro subsequently changed the project delivery method from design/build to design/bid/build, meaning Metro is now completing a design that will be fully approved for construction before potential contractors are invited to bid on it.

For more information on the project, visit Metro's project page here. See the full presentation from the recent CAC meeting here. Take the survey in English or Spanish. And track our coverage of the development of the project below:

- December, 2013: Dear Santa, Please Bring Us an Active Transportation Corridor Along Slauson, but Don’t Forget the Community in the Process (background on the plan; lack of outreach)

- March, 2014: Feasibility Study on Rail-to-River Project Takes Another Step Forward (plan begins to come together; outreach still a major problem)

- October, 2014: Motion to Move Forward on Rail-to-River Bikeway Project up for Vote Thursday (breaks down the feasibility study in more detail, costs, timeline)

- May, 2015: Planning and Programming Committee Recommends Metro Board Take Next Steps on Rail-to-River ATC (more on costs, timelines)

- October, 2015: The Rail-to-(Almost)-River Gets Boost with $15Mil TIGER Grant (yay, actual money!)

- May, 2016: Metro Awards Contract for Environmental Study and Design of Phase I of Rail-to-River Bike Path (OMG it is actually happening; request that outreach finally be meaningful)

- August, 2016: Metro Explores Alternative Rail-to-River Routes Through Southeast Cities (where we learn Metro and the Southeast Cities do not play together well)

- October, 2016: Metro Asks South L.A. Stakeholders: How Would You Use Rail-to-River Bike/Pedestrian Path?

- December, 2016: Rail-to-River Route Through Huntington Park, Bell Emerges as Best Candidate; Community Meeting December 8 (The Randolph Street option emerges as the favorite while also the most expensive and most complicated option; Community Advocates demand Metro handle outreach better and incorporate walking into plans better)

- December, 2016: Preview Some of the Design Options for the Slauson Segment of the Rail-to-River Bike/Pedestrian Path (self-explanatory)

- January, 2017: Metro Seeks Input on Design Options for Segment A of Rail-to-River Bike/Pedestrian Path

- July, 2017: Metro Offers Update on Rail-to-River Bike/Ped Path Design; Project to Break Ground Mid-2018

- December, 2019: Rail-to-Rail Bike/Ped Path along Slauson Delayed but Moving Forward