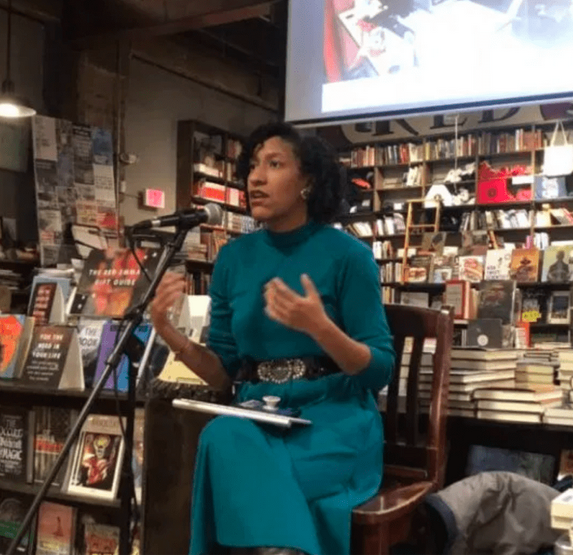

As founder, convener, and editor in chief at the The Black Urbanist, Kristen Jeffers explores land use, planning and transportation systems while centering the black, queer, and feminist voices. A native of North Carolina, she is also an author, textile artist and designer, urban planner and activist. Streetsblog sat down with her to talk about how she sees the conversation about street safety shifting in light of the most recent extrajudicial police murders, the subsequent uprisings, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

For many years, you and other people of color who work in transportation and the built environment have been challenging your white counterparts to confront street safety beyond car traffic, including police brutality against black and indigenous people of color and a wide range of other factors. Have you seen the conversation evolving in the wake of the last week's protests to center BIPoC voices?

Obviously, we’ve had escalations over the past week, but [the conversation about how to keep our streets safe] is rooted in centuries of oppression. ... It echoes back to the beginning of American slavery in 1619. It echoes back to the first colonization in the Americas. It echoes back to why police were created in many states in the first place: to protect landed interests like slaveowners.

Over time, cities began to adapt these police forces for other purposes, but it was still primarily about protecting and serving moneyed interests. Given that history, it shouldn't surprise us that there’s a ton of documentation of police brutality towards black people today — and for every case that’s documented, there are so many that aren’t documented. Our streets have never really been safe for black people — and that's before we even talk about gendered violence, and violence towards queer and trans people, and violence to people on the basis of their size, or their gender expression.

So when we get into these Vision Zero plans, often we talk like we’re doing people a favor; we're making streets safe! But then, in practice, we just use Vision Zero approaches to laser in on minor infractions in a way that hurts communities.

For instance, many cities have seen the advantages of installing speed cameras — but not to cut down on driver speeds. They configure them in such a way that they can automatically generate tickets just to create city revenues. And then you see tickets issued disproportionately in areas with disproportionately black people and poor residents, because that’s where the cameras are installed. I live right on the Prince Georges County, Md. line, and that’s where you see the cameras. I don’t see that many cameras in neighborhoods with larger white populations, including ones I've lived in myself in the past.

How has the COVID-19 pandemic deepened the conversation about race and equity in transportation?

Let's talk about opening up street plazas. Especially as we come out of peak of the COVID-19 curve, obviously people mean well, but so far, we're only really talking about opening certain outdoor spaces for certain reasons.

So we'll say, for instance, it’s okay to have a restaurant plaza; we say it’s okay for people who paid lots of money for a meal to use that public space to eat; it’s okay for folks, who are predominantly white, to gather en masse for that. And we'll also say it’s okay for restaurant workers, who are primarily black and brown people who don’t have access to vacation days they can use to maintain their livelihood if they don’t feel safe in their workplaces during a pandemic, to go to work in those spaces, to essentially be forced into front-line jobs. But when black people choose gather to participate in political speech — even when people gather to participate in protests in support of black people — well, of course that's still an issue.

there are two americas: one fights for black lives and the other fights for brunch pic.twitter.com/TFNsKghfmR

— ziwe (@ziwe) May 31, 2020

So it's like, how do we create a system where people can choose to be on the front lines? And then, how can we create a transportation system that supports those choices?

In the United States, it's being treated as a necessity for the poor, black and brown people who disproportionately make up the essential professions to go to the front lines. We're not giving them those choices. They have to get to work. But then we turn around and say, "Oh, well, everyone’s working at home now; people aren’t going to work like they used to, they aren’t driving cars, so we can just open up the streets!" But a lot of these essential service industry jobs are located far away from where people live, [so walking and biking to work on an open street isn't an option]; some cities are ignoring the fact that these workers are usually taking the bus, or else they’re driving.

So it’s one thing to say we’re going to drop a lane to do bus rapid transit to get those essential workers where they need to go safely and quickly; it’s another thing to do a woonerf and ignore the essential workers that need to come and go in buses and, yes, in cars. [Editor's note: Oakland's Slow Streets program is an example of a car-limiting project that faced pushback in communities of color. Read Streetsblog's interview with Warren Logan, the city official who oversaw the project, to learn more about how the city altered the program based on feedback.]

A thread I’ve noticed among women of color in my networks is a resistance to the word “urbanist.” Has your relationship to that word changed since you adopted the Black Urbanist moniker a decade ago?

I do identify with the word “urbanism,” and also with the term “friend of the city.” For me, “friend of the city" means being someone who advocates for every citizen to live in a just environment. I’ve always been fascinated with maps; I’ve always been fascinated with how people come together in urban spaces.

Now, that said, there is very much a classist undertone to the word "urbanist." It’s also biased; if you hear the world "urbanism," you don’t automatically think of that as a term that includes rural communities. I make that connection in my head, but I understand why people don’t. There have been times when I’ve thought about saying I’m just a "place-ist," but then even that assumes a certain definition of place, as a literal, physical space that you put a stake in.

At this point, all I can say is that anything that I do is going to convene people and create conversations in a way that centers black, queer, feminist people — and that centers black trans people, and is mindful of the fact that we, as black people, were brought to lands that were already stolen from indigenous first nations folks. I don’t begrudge anyone who doesn’t relate to the word "urbanist," but I do hope we can help create a community that examines that word, that examines what we’re asked to do under the banner of that word.

You can support Jeffers's work through Patreon, or get involved by attending one of her upcoming conversation circles for black and indigenous people of color, white allies, and people of all identities who want to learn how to use media to advance just and equitable urbanism.