The outbreak of COVID-19 has residents of dense American cities wondering whether they'd be safer in the suburbs right now — but experts are urging them to keep calm, carry on, and stay put in their downtown homes.

It might seem like strange advice at first. Yesterday's issue of the New York Times bestowed the ignominious title of "epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic" on the Big Apple, and Twitter erupted with jeers from suburbanites who aren't having to contend with five roommate-apartments and crowded public parks as they attempt to socially distance themselves. Even the Boston Globe chimed in with a smarmy editorial about how Americans are embracing their "suburban instincts," with no mention of the fact that the American suburb is barely a 70-year-old construct.

But experts are warning that early stats about outbreaks in dense cities don't give Americans the whole picture — and in many ways, people who live in the suburbs are actually worse off than their urban counterparts in this challenging global moment.

By and large, the communities with the highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases are also the ones with the greatest access to COVID-19 tests, not to mention the largest populations living within their borders. The state of New York, for instance, has performed 61,401 tests at last count, and 24.7 percent of patients tested positive; by contrast, only 3.4 percent of West Virginians who've gotten tested for COVID-19 had the virus, but the entire state has only performed a statistically negligible 464 tests total. More to the point, nearly five times as many people live in the five boroughs of New York City than in every town in the entire Mountain State combined— and we won't have a meaningful picture of the per capita impact of the novel coronavirus in any U.S. city until testing expands to more places.

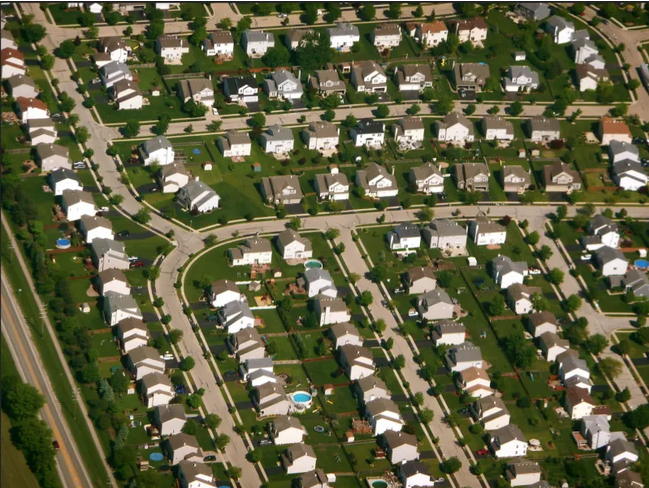

But here's what we do know: even in test-rich New York, the city's suburban borough, Staten Island, actually has the highest rate of infection, with 14 more cases per 100,000 residents than ultra-dense Manhattan. And even though we don't know if that pattern will hold true for other regions, we do know this: more than almost any other neighborhood type, suburbs are isolated, radically unsustainable places that are home to a public health crisis even in the best of times, because of their epidemic levels of traffic violence caused by the excessive driving suburbanites are forced to do because of bad urban planning.

And all three things are going to make it that much harder for suburban Americans — a group of people who, don't forget, are increasingly poor — to weather this storm.

Here are a few reminders of why if you need a refresher.

Suburban streets kill

It's one of the most under-studied realities of the transportation planning profession. But ask any pedestrian who's ever had to dart across a stroad, and she'll tell you: suburban road design is deadly for vulnerable road users. And in an unprecedented era when going for a walk in the neighborhood is about the only thing Americans can do outside the home, that's terrible news for suburbanites who are sheltering in place.

A 2019 study found that the densest parts of Philadelphia — namely, its urban downtown — actually has a lower rate of traffic crashes than suburbanized neighborhoods that surround them. And the contrast is even more dramatic when researchers control for lower rates of people who walk for transportation in outlying regions.

Federal crash statistics don't differentiate between collisions in urban and suburban areas, but it's likely the Philly study's conclusions can be extrapolated out to a suburb near you. Year after year, the top 20 cities with the highest pedestrian fatality rates per capita are basically a laundry list of communities that have eschewed the low-speed grids that were traditional in urban areas for centuries and incorporated aspects of suburban road design into sprawling, high-population cities, from Orlando's infamous arterial stroads to the endless strip malls of Albuquerque.

We've said it before, and we'll say it again: cars are creating a public health emergency in American cities every single day of the year — and if we let COVID-19 fears become an excuse for letting cities sprawl out even further, we will accelerate a traffic death crisis that claims 106 American lives every day, possibly without slowing coronavirus deaths much in the process. (More on that last part later.)

Suburban healthcare is broken

Yes, more and more healthcare providers are moving to the suburbs every year to improve their access to wealthy patients — but like everything else in the suburbs, those facilities are still fairly spread out. Meanwhile, suburban poverty is has risen catastrophically over the last decade.

So what do you get when you mix a large population of poor, largely uninsured people with a land use pattern and transit-poor transportation planning that makes it physically difficult to access doctors, even if they do take the financial gamble of seeking out care? Not a great recipe for a pandemic response, that's what!

The average suburban dweller lives 5.6 miles from the nearest hospital, compared to 4.4 miles for an urbanite. Those might seem like comparable distances, but when you factor in how dismal most suburban transit is, that 5.6 miles might as well be 50 for a poor, sick person who can't afford a car or the gas to put in it in a faltering economy, much less a pricey ambulance ride.

The suburban development pattern has always been a disaster for the health of poor Americans, especially when you factor in all the ways that autocentric streets make us more sedentary. But in an era when stopping community spread of a potentially deadly virus is our best defense, our sprawling healthcare system itself could be a time bomb — especially if we keep shutting down emergency drive-thru testing centers when wealthier residents complain, as did the residents of Darien, Conn.

It's time to re-urbanize our suburbs — and that includes putting acute care healthcare providers back in our neighborhoods. That will have to happen in concert with decentralizing our medical system, and in particular, unf*cking our medical malpractice insurance industry that forces would-be neighborhood doctors to ally themselves with large hospitals if they want to afford to open a practice. But it may be crucial in our new reality.

Suburban life is socially isolated — not just socially distant

Here's the upside of New York City's crowded parks right now: even while social distancing, New Yorkers can still see and interact with other human beings at a six-foot remove. That's not so easy for suburbanites on single family lots with deep setbacks.

Experts are beginning to speculate that loneliness and chronic stress could decrease the body's ability to fight off COVID-19, as those emotions are proven to do for other viral diseases. And even setting aside the potential health impacts, the psychological toll of forgoing contact with other people is putting a strain on millions of Americans right now that experts anticipate will have a profound psychosocial impact on much of the population for months or years to come.

Urbanites, at least, can lean out their apartment windows and have a sing-a-long with their neighbors, as these Milanese citizens do every day. And just try doing a socially distant scavenger hunt in a sprawling subdivision with long distances between homes. Ditto this socially distant block party out of San Francisco.

...But suburbs are also connected to cities, so they can still spread disease

Here's the thing about all the arguments that we need to suburbanize if we want to fight COVID-19: we've been saying a version for the same thing about infectious diseases for centuries. As Citylab spelled out early in the pandemic, our current iteration of plague dread isn't all that dissimilar to early 20th-century reactions to influenza and 14th-century reactions to the Black Death.

But we don't live in an era where taking a carriage ride to your summer home in the countryside was a great way for a nobleman to avoid infectious disease anymore. We live in a time when cities and suburbs are deeply connected — largely by cars. (After all, suburban New Rochelle, about 15 miles north of New York City, was itself a COVID-19 epicenter earlier in the outbreak.)

For centuries, a raft of land-use policies and economic incentives have encouraged Americans to drive frequently from the city to the suburbs and vice versa, whether to get from a suburb to a job center in a large metropolis (or from a city neighborhood to a suburban office park, depending on your city's particular breed of land use of dysfunction). And even the most cloistered American often has no choice but to visit a big, centralized grocery store right now, since healthful corner stores have been largely purged from our neighborhoods over the course of the last seventy years. Even as non-essential travel plummets in the wake of city shutdowns, city dwellers and suburbanites alike will still meet in the coming months, whether at work or in the toilet paper aisle.

The difference, of course, is that at the end of the day, suburbanites will return from those vanishingly few shared spaces to isolated homes that are further from necessary healthcare and surrounded by perilously dangerous streets to boot. That isn't the way Americans should have to spend this anxious time — or any time. Let's be sure to remember that once this pandemic is over.