Note: GJEL Accident Attorneys regularly sponsors coverage on Streetsblog San Francisco and Streetsblog California. Unless noted in the story, GJEL Accident Attorneys is not consulted for the content or editorial direction of the sponsored content.

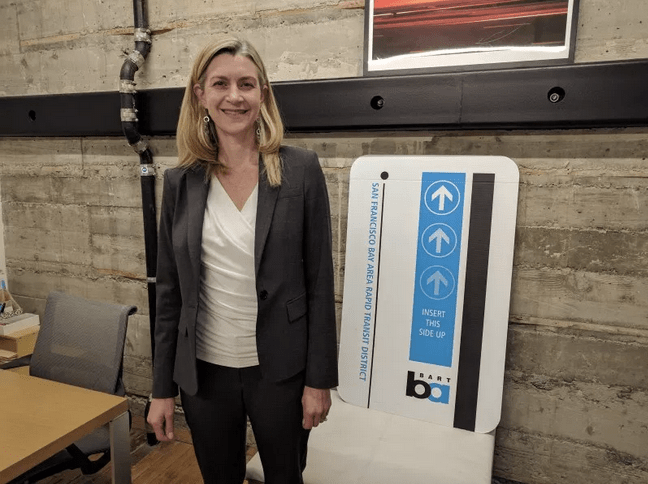

Earlier this month the San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association, better known as SPUR, welcomed its new President and CEO, Alicia John-Baptiste.

From SPUR's announcement:

John-Baptiste will be the first female president in the organization’s 112-year history. She became SPUR’s Deputy Director in 2015 and had previously held positions as Chief of Staff of the San Francisco Municipal Transit Agency (2012-2015) and of the San Francisco Planning Department (2005- 2012). She succeeds Gabriel Metcalf, who led the organization from 2005-2018.

John-Baptiste had already been serving as interim head while the agency conducted its search to replace Metcalf.

Streetsblog sat down with John-Baptiste Thursday morning at the organization's Oakland location to discuss her vision for the future of SPUR and the Bay Area.

***

Streetsblog: So we took a picture of you for this Q&A standing in front of a giant mag-stripe BART ticket. I'd think those tickets are something SPUR wants to get rid of, considering it only works on BART and none of the other transit systems in the region. We have Clipper, of course, but fares are still irrational from system to system.

Alicia John-Baptiste: We’ve been working for some time on concepts of seamless transit. I think the future that we’re striving towards is one where it doesn’t matter which service you’re using, you can move easily and almost transparently between systems which would require greater fare integration than we’ve had today. It’s something we’ve seen Toronto do successfully, as well as other cities in the world. When you do that, you see ridership increases and ultimately we’d like to see transit be the easiest and most convenient choice that we can make.

SB: San Francisco has a "transit first" policy. Yet we've written at Streetsblog about how the M Ocean View, as just one example, waits behind left-turning cars going into the Stonestown Galleria. Why is there such a disconnect between the declared policies of our cities and the reality?

AJB: We designed our regional transportation systems in the 1950s and 1960s, at a time when our population was less than half what it is today. We also weren’t a global employer. And that transportation system was largely designed around the car. The system no longer works. And we haven't invested in infrastructure as we’ve grown and changed as a region, so it shouldn’t be surprising that it doesn’t perform the way we want it to now.

SB: So what's the solution?

AJB: Ultimately we need a really transformative reinvestment in the system. If we want a system that works for our employment patterns and living patterns and our desire to experience the Bay Area as a single place, then we need to invest in the types of systems we see used so successfully in other parts of the world.

SB: So more rail?

AJB: High-performing rail; a rail system that functions as an integrated system, where you have hubs and spokes so you can turn up at your station without having to do a lot of advanced planning, at any time of day, with a reasonable level of frequency. Those are the types of changes we need to make. They won't be cheap. If we really want to get to a place where we can live our transit-first policy in San Francisco and the region, we're going to have to be willing to look at what the big-scale system investments are and find ways to fund it.

SB: So a second Transbay tube? Walk me through your vision.

AJB: I think it’s bigger than that. There are certainly big projects that would help us have an integrated system, but I think it’s more a reorientation in how we think about what we already have. If we were able to take much of our existing rail system and start planning it at a network scale we could have really different functionality. It means more service so we have to expand the capacity that we have today, but it must be followed by an investment in operations and infra that we haven’t achieved as of yet.

SB: Earlier this week we took a ride on BART with an operator. One of the limiters on service frequency is the money it costs to run trains. That could be pushed way down by not requiring an operator in the front of every train to push a door-close button. Do you see a future for automated transit?

AJB: It is probably inevitable. What I want to make sure is that it's thoughtful--at least how SPUR sets up its recommendations. We know from an economic standpoint that we’ve been losing middle class jobs as a region. BART and Muni operators are still really solid middle-class jobs. To the extent that those jobs are automated, we have to be really thoughtful that we don’t lose that pathway for that population--we want people to be able to stay in the Bay Area, so we have to think about what the transition could look like. We want to be smart as we advance and guide changes that are coming in a way that helps people and gets more efficiency out of the system.

SB: I guess that speaks to the larger issues of automation, such as autonomous deliveries and drivers?

AJB: Yes. SPUR is working on a regional strategy, looking at a civic vision for the Bay Area out to 2070. How do we sustain a thriving economy, knowing that the wealth we create can be used to meet social needs? How do we ensure we are creating jobs that don’t just serve the upper margins, but also create opportunities in the middle? This is a challenge we’re facing nationally. But we have a massive need to invest in infrastructure, so that can translate into opportunities for people.

SB: That makes me think of projects such as High-speed Rail, which provide needed transportation but also creates high-paying jobs in the Central Valley and elsewhere. What did you think of Gavin Newsom's State of the State speech and High-speed Rail?

AJB: The ultimate message was that HSR is an essential investment in California and that we can get it built by focusing on completing the components that are under way now. I would agree HSR is an essential investment for California. We need to make it, particularly in the Bay Area, so that we can get people form place to place without spending three hours in a car. The way to do that is with high-capacity transit and that means rail, an efficient express bus network, and local investments so people can walk and bike to places they need to go.

SB: Walk, bike, and ride scooters?

AJB: Sure. People love scooters.

SB: We've had a terrible year in San Francisco safety wise, including the recent death of a cyclist on Howard Street. Why are we tolerating such dangerous spaces in our cities?

AJB: It’s both an infrastructure question and a land use question. On the land use side we need to assure that our growth is directed in such a way that people can walk from home to shopping to work to sports or entertainment. On the infrastructure side I think the Vision Zero effort has done a lot--it's raised consciousness and resulted in investments to enhance safety. But we continue to struggle with the question of parking, because so much of what needs to be done to protect pedestrian and bikes is to remove parking from the curb. It’s hard for people to imagine a world when they don’t need their car, when they can not consistently and reliably use transit for all the trips they need. So there's a need for a concurrent investment in transit to help that process move along. But ultimately we need protected bike lanes. We're starting to see the results, such as on 2nd street; that’s been in the works for years. I think that those kinds of changes will make a difference. I would like to find ways to move our capital investment more quickly, but I think it means rethinking the rules around process.

SB: Maybe less outreach and more construction?

AJB: Outreach is important because you want to know how people will be impacted by the changes you are making. But at the same time because the contracting process and the environmental process take as long as they do, the outreach becomes stale and that leads to endless cycles of re-thinking and reanalyzing.

SB: So what's the source of the problem?

AJB: We have the perennial conversation about CEQA reform. San Francisco has done a lot of work to adjust CEQA with its transit-first policy, and that’s really valuable, but there’s more that can be done. On the regulatory side, we should really be thinking about how many approvals are required before we are able to implement projects. On the contracting side each rule is very well intentioned, but when you look at them in the aggregate they slow the process. We need to look through what we’re trying to accomplish in contracting and see if there’s an opportunity to streamline.

SB: Do you have a specific rule you'd change?

AJB: I remember when working in the city there was a prohibition on using hardwood from Burma.

SB: Really? So you'd get rid of some of these regulations?

AJB: If they have no real practical application, if they're not essential to the work we're doing, yes.

SB: What's the difference between working for an advocacy organization versus working for SFMTA or S.F. Planning?

AJB: It’s so different. Working for a government agency, your job is to take all of the wants and needs of the residents and try to integrate those into the service that you’re providing in the plans. At the same time, we ask local government to be the holder of the public good. So you have to integrate the two--what’s best from a collective standpoint but you have to balance that with the individual perspective. Working in an advocacy perspective there’s a bit more freedom to think longer term about where are we trying to go and therefor what changes do we need to see happen and over what time frames, and more ability to be full-throated pushing for a particular vision. In advocacy we have more of an opportunity to present a vision and work towards achieving it.

SB: So at SPUR there's less need to consider parochial politics?

AJB: SPUR is not constrained and it allows us to then put forward an aspirational understanding of where we could go, knowing that we are not as beholden to the realities of the day-to-day implementation. Although we don't recommend things that just can’t get implemented. But, yes, we have the ability to think more expansively and that’s a big part of what our value is in the civic conversation.

SB: What do you think is the most important piece of legislation you've seen in the past year? SB-50, the "More HOMES Act"?

AJB: SB-50 starts to get at the imbalance that we have in the region right now. When I look at how we’re set up as a region we have structures and institutions in place that hold the local perspective--the individual perspective--and only a few institutions to look at the region as a whole. It’s not in balance right now. SB-50 is one path towards shifting that balance a bit. But we have a whole set of legislation moving through the process right now that could really have an impact on how we manage housing. CASA legislation, when taken collectively, will have a big impact.

SB: And what's the worse piece of legislation in California, going back as far as you like?

AJB: We need to reconsider Prop. 13. We have the split-rule coming, potentially, between commercial and residential. But I think we should be solving for the disincentive that Prop. 13 creates for cities to build housing. We lock in property tax rates at a level that doesn’t keep pace for cities to keep up with the costs of housing. So cities are incentivized to create job, but not housing, which is why we have the affordability crisis that we have today. Changing that incentive structure is important. The answer may not be that we adjust property tax rates or eliminate Prop. 13. We’ve long advocated for a form of regional tax sharing, so cities that do accommodate housing can benefit from the taxes that are created in the cities next door.

SB: Speaking of cities next door, SPUR did a talk a while back about whether the Bay Area would have been better off with a borough system--so taxes from jobs in San Francisco could help pay for infrastructure throughout the region. Would we have been better off if Oakland, for example, were a borough of San Francisco?

AJB: It’s a hard question to answer. One of my areas of curiosity is how the identity of regions evolve. If you travel and people ask where you're from, you might say California. Within the Bay Area you might name your city or your neighborhood. But our collective identity might evolve into being more "Bay Area" than city.

SB: What is your favorite city?

AJB: My favorite city is Dakar, Senegal, I love that place. So vibrant.

SB: As a model for the Bay Area?

AJB: Hmm. That would be Toronto. It's an amazing city with high degrees of integration, racially, socially, economically. It's a city that takes a regional perspective, as well as having it’s own identity. There's a high degree of social investment. We could learn lots from Toronto. I also spent some time in Copenhagen. The bike is a primary form of transportation, to the point where you see lots of people on bikes who are not "bold and fearless" as the classifications go. Literally everybody is on a bike--moms with three kids with a cargo bike. It's so normal. And the infrastructure is amazing. And they’ve figured out how to manage their housing in such a way to provide for much greater degrees of social housing than we’ve ever been able to offer in the Bay Area.

SB: Okay. I've made you dictator of the Bay Area for six months. Solve our transportation problem. What do you do?

AJB: Let’s get the mega regional rail system built out, let’s get the second crossing built, let’s get Dumbarton, the connection to the Central Valley, get the highways set up for an express bus network, rebuild our bike lanes, redesign streets for people, not for cars.

SB: Sounds a little ambitious for six months. What could you literally do in six months?

AJB: We have this publicly owned space called streets--I'd make them for people.

SB: So severe speed limits in cities, protected bike lanes, more car-free streets?

AJB: I think we could literally delivery something like that in six months. It would be so transformative about how it feels to live in the Bay Area and the level of freedom and connectivity that people would have.

SB: And forget time constraints, what if I just write you a check for $20 billion?

AJB: I need more than that.

SB: Sorry, that's all I've got. And you can only spend it on one thing.

AJB: Then I think it’s going to be the East Bay's rail system. So a direct connection out to the Central Valley and huge capacity improvements from Sacramento to San Jose.

SB: So the Capitol Corridor?

AJB: Yes, because we have so many people pushed east and north and south, and so invest first on the side of the Bay where people are being pushed by our affordability problem makes the most sense to me. But, yes, we need similar investments on both sides of the Bay, and the second Transbay crossing, but I think I would do the East Bay first.

SB: Okay, one last fantasy question--I send you back in time, Terminator style. Reverse one single decision.

AJB. Hmm. I’m torn between Prop. 13 and the decision to curtail the BART system.

SB: You mean that it doesn't go to Marin? And that it didn't originally go to San Mateo County?

AJB: Exactly. You know the adage that the best time to plant a tree was 40 years ago, the second best time is now. So the best time to expand BART would have been when we built it. The next best time is now.

SB: Okay, so--

AJB: And when I say BART, I mean rail.

SB: Right, so you just mean a high-capacity rail network should have been built, but not necessarily to BART specs. When I was once asked the same question, I said I'd have changed the decision to make BART non-standard gauge, so now we could be talking about extending BART on disused and lightly used freight lines.

AJB: That's a good one too.